The Railways of Merton

by Lionel Green

by Lionel Green

In The Railways of Merton Lionel Green sorts out the tangle of the Borough of Merton’s railways. He gives dates, names of companies, and which later amalgamated with what. The book includes a very clear map and illustrations.

ISBN 1 903899 10 9

Published by Merton Historical Society – September 1998

Further information on Merton Historical Society can be obtained from the

Society’s website at www.mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk , or from MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1998

Merton Library & Heritage Service, Merton Civic Centre, London Road,

Morden, Surrey. SM4 5DX

Author’s Preface

Author’s Preface

The method adopted has been to recount all proposed railway schemes

chronologically until the formation of the two main railway companies

(LSW and LBSC). Thereafter, only successful projects have been

included. Lionel Green

List of Railway Companies and Abbreviations:

C&SL City and South London

K&L Kingston and London

L&B London and Brighton

L&C London and Croydon

L&M London and Manchester

L&S London and Southampton

LBSC London Brighton & South Coast

LC&D London Chatham and Dover

LSW London & South Western

M-E Morden – Edgware

SE South East

SE&C South Eastern & Chatham

SIR Surrey Iron Railway

SR Southern Railway

TM&W Tooting Merton and Wimbledon

W&C Wimbledon and Croydon

W&D Wimbledon and Dorking

WLE West London Extension

WM&WM Wimbledon Merton and West Metropolitan

© L. Green 1998

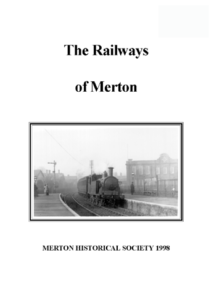

Cover Photo: Last through train from Wimbledon to Ludgate Hill,

Merton Park 2/3/29 copyright H C Casserley (ref 5638)

The building on the right was the Rutlish School Science block

which was destroyed by a flying bomb in October 1944

13 I. Nairn and N. Pevsner – The Buildings of England – Surrey – 1971 – 2nd.

Edn. p. 371.

14 John Innes (see page 29) objected to the name of ‘Lower Merton’ with its

hint of an inferior situation and persuaded the railway company to change

the name. On 1 September 1887 it was changed to Merton Park, fitting in

with John Innes’s desire for a park with roads shaded by forest trees.

15 Trains where the engine did not run round at terminals but remained at one

end, regardless of direction of running.

16 Opened as ‘Old Malden and Worcester Park’ and renamed February 1862.

17 First opened as ‘Hayden’s Lane’ but renamed ‘Haydons Road’ from 1 October

1889.

18 For tracing the changes in layout of Wimbledon station see Railway World

– January 1961, for an article by Geoffrey Wilson with plans.

19 Train Operating Council (T.O.C.) Minute 3947 1 October 1923.

20 The fourth rail on the District line is normally an insulated negative return

whereas on the former LSW system, an earth return through the running

rails is used. In order that all trains can use the section from East Putney to

Wimbledon, the centre (fourth) rail is not an insulated return but merely

provides contact with the negative shoes of District trains. It is therefore

bonded to the running rails to form a return circuit. At Putney Bridge

special resistances protect the differing systems as well as a train length

section gap.

21 This was not a new idea. Between 1854 and 1867 the LNWR issued free

season tickets (house passes) to potential house builders. The aim was to

increase the demand for coal and consumer goods along new routes as well

as family travel.

22 Ludgate Hill was closed from 3 March 1929 as it could not accommodate

the eight coaches of multiple unit stock.

23 C.F. Klapper – Sir Herbert Walker’s S.R. – 1973 – p. 190.

24 Wimbledon and Merton Annual – 1905 – p. 114.

25 The names of all the stations were agreed at T.O.C. (Min. 6281) – 1 October

1928.

26 This was a re-used bridge from near Margate.

27 Operated on ‘one engine in steam’ arrangements – probably the first instance

of working without a steam engine.

28 C.G. Dobson – A Century and a Quarter – 1951 – p. 121.

29 It is beyond the scope of the present booklet to relate wartime incidents of

the railways but on the first local air raid at 5.35pm 16 August 1940, the

South Wimbledon substation was put out of action. Trains, however, were

suspended for only two hours.

39

Notes and References

Notes and References

2 Charles E. Lee -Early Railways in Surrey – 1944 – p. 10.

3 B. Morgan – Railways – Civil Engineering – 1973 – p. 19; the gauge was

determined by W.G. Tharby – Railway Magazine No. 113 – (1967) p. 465.

4 W.G. Tharby – Surrey County Magazine – July 1975 p. 101.

5 James Malcolm -A Compendium of Modern Husbandry … of Surrey 1805

– Vol I p. 25.

6 R.A. Williams – The London and South Western Railway – 1968 – Vol. I

p. 22.

7 Eventually all railways adopted London time so that standard time

measurement became known as ‘Railway Time’ and the joint action of

railway companies prevailed upon the Government to establish an official

standard time. This was done by statute in 1880 when Greenwich Mean

Time was adopted.

8 W.E. Gladstone (as President of the Board of Trade) introduced a Bill in

1844 which required railways to run a train on all lines, calling at all stations

at least once a day with carriages which were protected from the weather

and with seats (Railway Regulating Act – 9 August 1844). These were

known as ‘parliamentary trains’.

9 London and South Western Gazette – July 1890. He was Charles S. Loveless

(1829-1893) who married Eliza Smith, daughter of Thomas the coppersmith

at Wimbledon in 1856.

10 R.A. Williams – The London and South Western Railway – 1968 – Vol. I

p. 227.

11 George Parker Bidder, the railway engineer, came from Devon and achieved

early fame as the ‘Calculating Boy’ answering at sight all sorts of difficult

arithmetical questions. At the age of 28 he worked for Robert Stephenson

and became a leading civil engineer. He lived at Mitcham Hall before moving

to Ravensbury Park, a house he had built off Bishopsford Road, Morden.

His son, George Parker Bidder Q.C. is remembered for preserving Mitcham

Common for public use, and Col. H.F. Bidder, grandson of the engineer,

undertook archaeological work in the borough at the Anglo-Saxon cemetery

at Mitcham (1891-1922) and Merton Priory (1921).

12 The station was originally called Beddington but that community complained

that the station was two miles away. In January 1887 it was renamed

Beddington Lane, and Waddon was renamed ‘Waddon for Beddington and

Bandon Hill’. Waddon Marsh was not opened until 6 July 1930.

38

Introduction

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the rolling resistance of a cart

could be reduced if its wheels were contained on well aligned rails, with a

flange to afford guidance. Early in the 17th century several coalfields in

north-east England laid wooden rails to move loaded wagons from the

coal face. The gauge was dependent on the width of carts currently in use

in each locality, usually between four and five feet. Many other mineral

railways were built thereafter in many parts of the country except in the

south. Under the Highways Act 1773 (13 Geo. III cap. 84 sect. 12),

vehicles using public roads were restricted to a width of 4 feet 6 inches

and from that date no plateway (i.e. iron plated railway) exceeded this

gauge.

‘The first public railway’

In 1799 various schemes were proposed to transport military supplies

between London and Portsmouth during the Napoleonic Wars thus avoiding

the French privateers who were harassing ships on passage to and from

London. William Jessop was asked to examine the possibilities of building

either a canal or a horse drawn railway. Supporters of the canal asked

Jessop to survey the first stage between Wandsworth and Croydon but his

report (9 December 1799) concluded that the scheme was impracticable.

The route would have to be close to the river Wandle for most of the way

and the canal would rob the river of a great part of the water supply

bringing complaints from the thirty mills and factories who depended for

power from waterwheels. John Rennie agreed with Jessop’s conclusion.

At the same time Jessop surveyed the route for a railway from London to

Portsmouth via Croydon and estimated it would cost £400,000.1 The

benefit of a railway over a canal was not a foregone conclusion as the

canals could easily hold their own against competition from the horse

drawn railways. One horse on a towpath could haul a greater tonnage in

a barge than in wagons on the best laid railway. The two forms were in

fact very compatible, with the railway excelling in short distances able to

overcome or use gradients, and the barge travelling long cross-country

journeys without having to trans-ship goods. When parliamentary sanction

was obtained for building canals, discretion was readily given to proprietors

to construct railways as feeder routes.

3

The first section of the railway from Wandsworth to Croydon was

incorporated in the Surrey Iron Railway (SIR) Bill submitted to

Parliament on 27 February 1801, which received the Royal Assent on

21 May (41 Geo. III cap. 33). Two amendments had been added by the

House of Lords, one stipulating ‘that where the said Iron Railway shall

cross any Turnpike roads or public highways, the ledge or flanch of the

rail for the purpose of guiding the wheels of the carriages, shall not

exceed one inch in height above the level of the road’. The other clause

prevented the branch line to the calico printing manufactory of Richard

Howard (near Phipps Bridge) being extended further. The reason for

this clause is unknown. Mr. Howard was one of several local

shareholders, and an extension would have assisted the Ravensbury

print works. The line was to have a road bed for a double track of 18

feet, unfenced. The Act stated that land to be taken should not exceed

twenty yards in breadth ‘except in those places where it shall be judged

necessary for waggons or other carriages to turn, lie or pass each other,

or where any warehouse, crane or weighbeam may be erected or where

any place may be used for the reception or delivery of goods …..’ In

these instances no more than sixty yards in breadth could be taken without

the consent of the owners of land adjoining. Lords of manors and

landowners on the railway could, and if deemed necessary were obliged

to, erect warehouses, in default of which the railway was empowered to

construct and charge rent on goods lodged therein.

The first section of the railway from Wandsworth to Croydon was

incorporated in the Surrey Iron Railway (SIR) Bill submitted to

Parliament on 27 February 1801, which received the Royal Assent on

21 May (41 Geo. III cap. 33). Two amendments had been added by the

House of Lords, one stipulating ‘that where the said Iron Railway shall

cross any Turnpike roads or public highways, the ledge or flanch of the

rail for the purpose of guiding the wheels of the carriages, shall not

exceed one inch in height above the level of the road’. The other clause

prevented the branch line to the calico printing manufactory of Richard

Howard (near Phipps Bridge) being extended further. The reason for

this clause is unknown. Mr. Howard was one of several local

shareholders, and an extension would have assisted the Ravensbury

print works. The line was to have a road bed for a double track of 18

feet, unfenced. The Act stated that land to be taken should not exceed

twenty yards in breadth ‘except in those places where it shall be judged

necessary for waggons or other carriages to turn, lie or pass each other,

or where any warehouse, crane or weighbeam may be erected or where

any place may be used for the reception or delivery of goods …..’ In

these instances no more than sixty yards in breadth could be taken without

the consent of the owners of land adjoining. Lords of manors and

landowners on the railway could, and if deemed necessary were obliged

to, erect warehouses, in default of which the railway was empowered to

construct and charge rent on goods lodged therein.

A meeting of the new company was held on 4 June 1801 with John

Hilbert presiding. He was a prominent resident of Wandsworth and at

the time was completing the purchase of the lordship of the manor of

Merton. At the meeting, Jessop’s appointment as engineer was confirmed

and George Leather was engaged as resident engineer.

The authorised capital for the SIR was £50,000 but construction costs

exceeded this and a further £10,000 was authorised by Parliament on

12 March 1805 (45 Geo. III cap. 5). The total length was just over nine

miles, and the line opened on 26 July 1803. A single track branch line

was also constructed from Mitcham to Carshalton (Hackbridge). This

was one and a half miles in length and was opened by June 1804.

4

responsible directly to the Ministry (now Department) of Transport from

1 January 1963. Under the Transport (London) Act of 1969, all came

under the control of the Greater London Council from 1 January 1970

through a new London Transport Executive, until the demise of the GLC

in 1986.

Recent changes

During 1996 the Government disposed of parts of the railway system as

franchises for private companies to operate services which in one respect

(freight trains) recalls the operation of the SIR in 1803. The infrastructure

(track, signalling, bridges, etc.) is owned by Railtrack which was set up

on 1 April 1994 and the Train Operating Companies pay to use the facilities.

These also reflect the pre-1923 companies, with the LBSC passenger

services mostly operated by Connex South Central, and the LSW by South

West Trains (Stage Coach Holdings). The Wimbledon to Sutton line

together with the upper loop to Tooting is operated by Thameslink. The

Wimbledon to Croydon service closed on 31 May 1997 and is to be replaced

by the Croydon Tramlink system before the next century.

The story of Merton’s railways has no ending but often repeats itself. It

began with a tramway which became a railway. That line now awaits

transformation back to a tramway where much of the route between

Mitcham and Waddon will follow the same alignment as the original.

West Croydon/Wimbledon – last days of steam – electrified 6/7/1930

(postcard by Pamlin Prints © 1969) (ref M82)

37

‘bulls eye’ in the centre. A canopy of reinforced concrete suitable for

subsequent commercial development flanked the central feature.

Overbuilding was done successfully at Morden in 1964. Traction current

was supplied from Lots Road power station (at 550 V dc) and the Morden

extension was the first railway to have an unattended electricity substation.

A manned unit at South Wimbledon controlled Balham.

‘bulls eye’ in the centre. A canopy of reinforced concrete suitable for

subsequent commercial development flanked the central feature.

Overbuilding was done successfully at Morden in 1964. Traction current

was supplied from Lots Road power station (at 550 V dc) and the Morden

extension was the first railway to have an unattended electricity substation.

A manned unit at South Wimbledon controlled Balham.

The new service commenced at 3.00 p.m. on 13 September 1926 following

the official ceremony attended by 400 guests. Everyone was allowed to

travel free until just after midnight and 35,000 took advantage of this

offer. The name chosen for the extended tube was the Morden – Edgware

Line and it became part of what was then the longest railway tunnel in the

world, 16 miles 1,100 yards (26.76 km.) from Morden to Golders Green

(via Bank). On 28 August 1937 the name was changed to the Northern

Line and on 3 July 1939 a tube extension between Archway (Highgate)

and East Finchley on the other northern branch increased the length of the

continuous tunnel to 17 miles 528 yards (27.84 km.).

The Morden extension was a success from the first, and within two years,

it was necessary to employ double deck (‘General’ open top) buses to

convey the hundreds of rush hour passengers emerging from each train

(33 trains per hour) to their newly-built homes at Worcester Park, Cheam,

Sutton, Carshalton and Wallington. Other buses brought traffic from

Ewell, Epsom, Banstead and Burgh Heath. A new type of rolling stock

was introduced for the extension, with improved ventilation and sound

proofing for the benefit of passengers making the comparatively long

underground journeys.

The red painted carriages were a familiar part of the underground railway

scene and performed sterling service for 40 years. Silver units (unpainted

aluminium) were introduced in April 1978.

On 13 April 1933 an Act was passed which formed the London Passenger

Transport Board (LPTB) and the Underground railways, together with

the bus companies, came under one control from 1 July. On 1 January

1948 all railways were nationalised and London Transport became one of

the five executives of the British Transport Commission. Further changes

were authorised in 1962 and the Underground Railways then became part

of the London Transport Board, an independent statutory authority

36

As work was progressing on constructing the railway through Merton,

a new resident arrived on 23 October 1801 to occupy his only English

home close by. He too was averting Napoleonic threats, but in a different

way, and two years after the opening of the railway, succeeded gloriously,

at Trafalgar. Nelson’s victory removed the urgency for a railway to

Portsmouth.

Surrey Iron Railway – a description

The rails consisted of cast iron plateways of angle-sections with a raised

flange, each about 3 ft. 2 in. in length resting on stone sleeper blocks

measuring approximately 16 inches square. Each rail end had prepared

notches for headless spikes which were driven into wooden plugs fixed

into each block. It may be assumed that the rails were supplied from

Jessop’s Butterley Works, Derbyshire, which was established in 1790

by Jessop, Outram, Wright and Beresford. The original rails proved

too weak and a heavier section was adopted when repairing. This had

an extra flange projecting downwards from the outer edge, deepening

between points of support to give strength to the weakest part.

The gauge was 4 ft. 2 in. which followed that in use on the colliery

railways of South Wales.3 The four inch tread on the plateway enabled

wagons to be accommodated with wheels up to 4 ft. 6 in. apart. The

horses drawing the wagons walked between the rails where the ballast

had been tamped hard, which ensured an absence of loose stones for the

horse to kick onto the rail. At level crossings packing was laid to reduce

the obstruction of the flange which in those locations was only one inch

high. Merton Road, now High Street, Colliers Wood, was crossed on

the level with the gates normally closed to rail traffic. The gatekeeper’s

cottage existed until 1964.4

At certain distances there were cross-over points – ‘a method of letting

the waggons pass from one road to the other by a short diagonal railway,

and by throwing or forcing aside a bar of iron moving on a pivot, which

enables them to move in and out with the greatest facility’.5 At points

of access were turn(table) plates.

5

Surrey Iron Railway

Toll Sheet

60 cm x 44 cm

Science Museum

6

The main lines up until then did not fear any competition from tube railways

assuming that they would only operate for short journeys within cities.

Sam Fay who became LSW Superintendent of the Line from 1899 to

1902 is reported as saying that he could not see anyone travelling to town

‘through a sewer’.

On 1 January 1913 the C&SL was incorporated into the London

Underground Group which reconstructed the line (1922-1924) with a

standard 11 ft. 8¼ in. diameter tube to Clapham Common. Then followed

an ambitious scheme to run trains through to Sutton (see above). After

agreement with the SR, the extended line was to terminate at Morden.

The sidings took the line almost up to the Wimbledon and Sutton (SR)

line but with no connection. Finance for the extension was guaranteed by

the Government under the Trade Facilities Act of 1922 and work

commenced at Clapham on 31 December 1923 and continued in appalling

weather. Cement, blue lias lime and aggregates were supplied by Hall

and Co. Ltd. at various points between Tooting Broadway and Morden,

using the same vehicles to remove excavated clay. This was difficult in

wet weather because of the nature of the clay and the fact that workers

underground could work regardless of the weather. Surface cartage had

to continue night and day on occasions and in order to anticipate

requirements, Messrs. Negretti and Zambra supplied daily weather

forecasts.28 Some of the clay was used to fill Hall & Co.’s disused gravel

pits at Mitcham. Other local carters were involved in the disposal of the

clay which was spread on the fields beside the Wandle (Liberty’s sports

field and Phipps Bridge estate). The sand pit in Morden Hall Park was

also filled, this being assisted with buckets on overhead wires from the

tube entrance beside Dorset Road. The old brick works pit in Green Lane

(Martin Way) was also filled in this way, later becoming Mostyn Gardens.

The railway was wholly tube construction except for the section under

Kendor Gardens and Kenley Road car park where a ‘cut and cover’ system

was used. It had been intended that this section should be in the open but

the presence of water near the surface caused a change of plan.

A feature of the new stations designed by Charles Holden (including

Colliers Wood, South Wimbledon and Morden) was a single adaptable

elevation in Portland stone with a large window bearing the Underground

35

stations were built to a standard design of 520 ft. island platform suitable

for eight-coach electric trains. An additional station was provided at the

request of the LCC who were embarking on a scheme for 9,068 dwellings

forming the St Helier Estate to house 40,000 people. This estate of 825

acres was built in sections between 1928 and 1936. The name

commemorates Lady St Helier, an alderman from 1910 until 1927, who

died in 1931. Because of the nearness of the tube railway at Morden,

little traffic came to the new station. The only freight facilities on the

line were provided at St Helier. These gave good service for many years

but were withdrawn from 6 May 1963. A private siding existed from

1954 until 1978 at Morden South for Express Dairy milk traffic from

the West Country.

stations were built to a standard design of 520 ft. island platform suitable

for eight-coach electric trains. An additional station was provided at the

request of the LCC who were embarking on a scheme for 9,068 dwellings

forming the St Helier Estate to house 40,000 people. This estate of 825

acres was built in sections between 1928 and 1936. The name

commemorates Lady St Helier, an alderman from 1910 until 1927, who

died in 1931. Because of the nearness of the tube railway at Morden,

little traffic came to the new station. The only freight facilities on the

line were provided at St Helier. These gave good service for many years

but were withdrawn from 6 May 1963. A private siding existed from

1954 until 1978 at Morden South for Express Dairy milk traffic from

the West Country.

Morden Tube Railway (1926)

The tube line to Morden originated as the City of London and Southwark

Subway Company which opened with 3¼ miles of tube railway from

King William Street to Stockwell. Services began on 4 November 1890

but the public opening was not until 18 December. The railway was

contained in tubes with an internal diameter of 10 ft. 2 in. Two tunnels

were driven through the London clay with a shield and lined with cast

iron segments using a method devised by Peter Barlow (d. 1885) and

developed by James Greathead (d. 1896). From the beginning it operated

with electric traction and thus became the first electric tube railway.

Powers to extend the line to Clapham Common were obtained in 1890

and the name was changed to the City and South London Railway (C&SL)

opening on 3 June 1900.

34

Unlike all previous railway projects, the SIR was not an adjunct to a

particular manufacturing concern but a transport enterprise in its own

right. The authorising Act gave power to construct the railway – not to

operate it. The SIR was a toll company i.e. empowered to collect dues

from wagon owners for the use of the railway in the same way as

Turnpike Trusts. Users provided their own rolling stock and paid

relevant tolls for the commodity, weight and distance. Train loads usually

consisted of five wagons drawn by a horse or large mule at an average

speed of 3 m.p.h. Carriers could join the railway at certain locations

with their own horses and wagons already loaded without trans-shipping

-although there is evidence that regular customers kept their own wagons

for railway use only. Company stables were provided at the access

points. The SIR was never a flourishing investment and shareholders

were paid only about 1% in dividends, the last being paid in 1825.

Following the success of the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway and

the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (both opened in 1830), the

locomotive was firmly established as the most suitable motive power

for railways and horse power ceased to be of consequence.

In 1838 the Croydon to Merstham extension of the SIR was closed in

order to provide a route for the London and Brighton Railway (L&B).

The remaining SIR could not compete with the faster goods trains of

the London and Southampton Railway (L&S) and the London and

Croydon Railway (L&C) opened in 1838 and 1839 respectively, and

traffic further declined. Finally in 1844 the L&S and L&B jointly

arranged to purchase the line for £19,000. This was never completed

by the L&S and the L&B was left to complete purchase on its own.

The Act of Dissolution was not sought until 1846 and the railway

officially closed on 31 August 1846.

No trace is visible in the borough today, but the two sections of Tramway

Path, close to Mitcham Station, and beyond Willow Lane towards The

Goat, keep its memory alive.

7

London and Southampton via Wimbledon (1838)

London and Southampton via Wimbledon (1838)

The original surveyor was Francis Giles who intended to build the line

through Wimbledon close to the village on the hill, but Lord Cottenham

had recently purchased a large area of the land west of the village and

wished to retain his privacy. Kingston coach operators also opposed the

railway approaching the town and obliged the railway to cut through

Surbiton Hill. Because of this southerly diversion the proposed station

was in the fields midway between Wimbledon and Merton and was so

named for many years. The deposited plans show the route crossing

Wandsworth Common and the river Wandle, passing the south side of

Lord Spencer’s Wimbledon Park and ‘afterwards through the low lands’.

The railway enters and leaves the borough on a 25 foot high embankment

but is on the level in between. When first constructed there was a level

crossing for Merton Road (now Durnsford Road). Just north of

Summerstown the line passed over the SIR beside Garratt Lane on an

arch 15½ feet high and 22 feet wide. When work commenced in October

1834, Robert Stannard, one of the contractors, was ready to make a start

at the terminus at Battersea but Giles directed him to Wimbledon, Kingston

and Merton where it was cheaper to hire labourers.6 The method Giles

used was to engage many small contractors concurrently at various

locations but this meant that the easier parts of each section were completed

and payment demanded before tackling the difficult parts. This caused

‘cash flow’ problems leading to increased costs, for when fresh contractors

were engaged they sought higher payments. Progress down the line was

hampered by the severe winter of 1836/7.

8

with the proposed Sutton line); the District Railway would have running

powers over the Sutton line; and the Southern Railway agreed to restore

the passenger service on the Wimbledon, Tooting and Streatham line.

The SR subsequently named their station Morden South,25 much to the

confusion of map makers of the 1930s. A suitable Bill was quickly

passed through Parliament but with further changes. The District

Railway had lost interest in running trains through to Sutton and instead

of the connection with District Line platforms at Wimbledon, the Sutton

trains would use the former LBSC platforms on the south side. The

Act of 1924 also transferred promotion and powers to the Southern

Railway. The estimated cost was £220,000 for land purchase and

£822,000 for works and equipment. There were further delays while

property was acquired and demolished and Board authority to commence

work was passed on 30 June 1927. It was typical of Herbert Walker to

save time and money wherever possible by using his own engineers’

men for the first mile and a half. Work commenced from the Wimbledon

end in October 1927 under the supervision of the Chief Engineer, Mr.

G. Ellson. Heavy engineering work was involved throughout the length

of the new line with 24 over/under bridges and embankments to avoid

level crossings and tunnels.

Within the Merton Borough are eight long steel girder under bridges

(many skew) with concrete floors – Toynbee Road (48 ft. 6 in.); The

Chase (42 ft.); Kingston Road (80 ft.); Whatley Avenue (52 ft.); Cannon

Hill Lane (55 ft.); Hillcross Avenue26 (57 ft. 8 in.); Epsom Road (120

ft.); and Love Lane. A contract was let to Sir Robert McAlpine & Sons

to construct the portion from South Merton to Sutton. Some of the

chalk surplus of over 500,000 tons from cuttings near Sutton was used

in the embankments to the north as well as forming road overbridges

such as the Martin Way ‘hill’ by South Merton station. Clay excavations

were dumped near Morden South station. The electric service from

Holborn Viaduct to Wimbledon via Tooting and Haydons Road was

extended to Wimbledon Chase and South Merton from 7 July 1929 as a

single track ‘train staff controlled’ portion27 from a temporary crossover

near Toynbee Road bridge. From 17 December (after 3 days of trial

running) further double track was available and whilst South Merton

was still the terminus, trains ran on empty to St Helier to reverse. The

33

the existing line by the provision of two further tracks between Putney

Bridge and Wimbledon. This was authorised on 7 August 1912 although

the work was never carried out. Towards the end of 1913 a new platform

for the District Line trains was constructed on the north side of

Wimbledon station but, with the delays, it was necessary to renew

previous authorities and to increase the authorised capital to £550,000.

This Act was obtained in 1913 but work on the railway had not

commenced at the outbreak of war in August 1914. The ending of

World War I brought further problems, including unemployment, and

use was made of the Trade Facilities Act 1921 to obtain a Treasury

guarantee to complete construction of the line. The prime mover was

now the Underground Railway Company and in November 1922 they

applied for powers to fulfil a comprehensive scheme costing £5 million.

Besides constructing the Wimbledon to Sutton line, they wished to

modernise and improve some of the existing underground facilities, and

to extend the City and South London (C&SL) tube from Clapham

Common to Tooting, Merton, Morden and connecting with their proposed

surface line to Sutton.

the existing line by the provision of two further tracks between Putney

Bridge and Wimbledon. This was authorised on 7 August 1912 although

the work was never carried out. Towards the end of 1913 a new platform

for the District Line trains was constructed on the north side of

Wimbledon station but, with the delays, it was necessary to renew

previous authorities and to increase the authorised capital to £550,000.

This Act was obtained in 1913 but work on the railway had not

commenced at the outbreak of war in August 1914. The ending of

World War I brought further problems, including unemployment, and

use was made of the Trade Facilities Act 1921 to obtain a Treasury

guarantee to complete construction of the line. The prime mover was

now the Underground Railway Company and in November 1922 they

applied for powers to fulfil a comprehensive scheme costing £5 million.

Besides constructing the Wimbledon to Sutton line, they wished to

modernise and improve some of the existing underground facilities, and

to extend the City and South London (C&SL) tube from Clapham

Common to Tooting, Merton, Morden and connecting with their proposed

surface line to Sutton.

which

pleased no one. The new Southern Group was blamed for the

failure and hasty negotiations took place in July 1923 when Sir Herbert

met Lord Ashfield and they agreed on a revised scheme. The SR was to

build the Wimbledon and Sutton railway; they would not oppose the

extension of the C&SL to Morden with a terminus at ‘North Morden’; a

carriage depot would be constructed south of the terminus but there

would be no connection with the Wimbledon and Sutton Line (the early

plans for the tube extension had referred to a junction at South Morden

32

The shares in the L&S dropped on the stock market which alarmed the

shareholders and the ‘Liverpool Parties’ from the north demanded that

the board engage another engineer to examine Giles’s amended estimates

for completing the line. The directors agreed and engaged Joseph Locke

whereupon Giles resigned in January 1837 and, with Locke’s

appointment as engineer, the small contractors at the London end were

dismissed and Thomas Brassey with his army of workmen engaged.

John Strapp was the assistant responsible for the section through

Wimbledon and Merton.

On 12th and 19th May 1838, private experimental trips were made

from Nine Elms to Woking and back, and on 21st May the line was

open to the public. At first no goods trains were run and consequently

no third class passengers (for at that time they travelled in open trucks

attached to goods trains). In June 1839 the company changed its name

to the London and South Western Railway (LSW), and in 1848 a new

London terminus was built and named Waterloo.

Train travel in 1845

At its inception the L&S ran five stopping trains each day between

Woking and Nine Elms but when the line opened throughout from

Southampton in May 1840 this was increased to eight up and seven

down stopping trains. The eighth train ran down empty. The fare from

Wimbledon to Nine Elms was 1/6d and 1/- depending on class and the

journey time was 18 to 20 minutes. A note appeared on the published

timetable that London time would be observed throughout. This is a

timely reminder that it was only with the coming of the railways that it

was found necessary to standardise timekeeping throughout the country.

Hitherto each community went by the church or municipal clock.

Mitcham time was Mitcham time right or wrong and no one in Mitcham

took any notice of the hours being struck by Morden church.7

Having selected the train, passengers had to arrive in good time to book

a ticket and allow for time variations. Until 1845 the booking clerk

issued a paper ticket over an open counter and the name of the destination

was inserted by hand. The Edmondson card ticket was first introduced

by the LSW in 1845 and became one of the most widely used railway

tickets in Britain until 1988. All intending passengers were handed a

9

bill of ‘directions and conditions’. Smoking was not allowed in stations,

on platforms or in any carriage. Even on receipt of the ticket a passenger

could only board the train if there was room. No passenger was allowed

to open a carriage door without assistance from the staff. Platforms

were much lower than today, only 1 ft. 9 in. above rail level, necessitating

a lower mounting step on all carriages. A hand bell was rung at least

half a minute before the departure of the train and the guard had then to

ensure that all passengers were seated, and all doors fastened. He then

showed a white flag or lamp to the engineman (red was danger, green

meant caution and white was for ‘all clear ahead’). The four-wheeled

carriages contained three compartments, and, in composite coaches,

the central first class compartment had better furnishings than the

flanking second class compartments over the wheels. The vehicles were

oak framed with pine panelling with fixed ‘dumb’ buffers, of padded

leather but without springing. In 1844 the LSW began to cover the

third class open trucks with a roof, fitting three compartments with

five-a-side seating.

bill of ‘directions and conditions’. Smoking was not allowed in stations,

on platforms or in any carriage. Even on receipt of the ticket a passenger

could only board the train if there was room. No passenger was allowed

to open a carriage door without assistance from the staff. Platforms

were much lower than today, only 1 ft. 9 in. above rail level, necessitating

a lower mounting step on all carriages. A hand bell was rung at least

half a minute before the departure of the train and the guard had then to

ensure that all passengers were seated, and all doors fastened. He then

showed a white flag or lamp to the engineman (red was danger, green

meant caution and white was for ‘all clear ahead’). The four-wheeled

carriages contained three compartments, and, in composite coaches,

the central first class compartment had better furnishings than the

flanking second class compartments over the wheels. The vehicles were

oak framed with pine panelling with fixed ‘dumb’ buffers, of padded

leather but without springing. In 1844 the LSW began to cover the

third class open trucks with a roof, fitting three compartments with

five-a-side seating. All carriages were non-smokers until 1868 with

no inside door handle provided until about 1900.

The Railway ‘Servants’

Numbered with the staff were policemen who acted as watchmen,

signalmen, and even ticket collectors. The police/pointsmen wore tall

hats with leather crowns, chocolate coloured coats and dark trousers.

The early trains relied on strict timekeeping for train safety, and each

station possessed a clock. Soon after 1840, rotating discs were set up

on the LSW main line and when aligned edge-on to the driver (i.e.

virtually invisible), the line was clear. From 1841 guards wore a scarlet

frock coat with lace collars and silver buttons; first class guards wore a

belt in addition.

The author’s great-grandfather joined the LSW in 1852 and has recorded

some early memories of his days as a guard.9 “In September 1858 I

was made a guard and my first trip was with the Necropolis train to

Brookwood. I had to take my seat on the roof of a composite carriage

(1st and 2nd class) used as a brake …. in those days we had another

brake commonly called a ‘booby hutch’ (only having an opening on one

side) and on one journey we had to cross the coupling to reach the

10

Wimbledon from 1889 John Innes considered that they might extend

their service to the parishes south of Wimbledon. He found that the

LSW preferred to strengthen their monopoly at Wimbledon rather than

risk opening up new areas which had a sparse population at that time.

With the failure of the 1891 scheme John Innes thereafter used his

energies until his death in 1904 to secure a quicker access from Merton

to the West End as well as the City.

In 1908 a further attempt for a Wimbledon and Sutton railway was

made but no Bill was presented to Parliament. A year later, a group of

landowners met in December, in Merton, and a Bill was progressed for

a railway with ten stations. The District Line Railway expressed an

interest in operating the proposed line without supporting the venture

financially. The LSW opposed the scheme because the District Line

Railway trains would have to cross their main line at Wimbledon and

be ‘working electrically’; they also considered that the District Line

Railway services were already overloaded. The LBSC also opposed

because it would reduce their traffic from Sutton to London and they

attempted to prove that their planned electrified services would be quicker

than the promoters’ estimate of 32 minutes to London. Royal Assent

was given on 26 July 1910 with powers for the District Railway to

operate over an end-on junction at Wimbledon station, passing under

Wimbledon Hill Road and serving the All England Tennis Ground, then

in Worple Road (with a station). The railway was then to pass under

the main line towards Broadwater Farm at the north end of Cannon Hill

Lane. This was to be ‘Cannon Hill Station’, and the line would proceed

to Merton Park, Morden village and Elm Farm. The estate of St Helier

was not envisaged at this time.

Because of the refusal by the LSW and LBSC to support the scheme,

the promoters were short of capital and they approached the District

Railway in March 1911. After negotiation an arrangement was made

whereby the landowners would find £6,000 a year for ten years and the

District Railway was to find the balance of the money to build the line.

This was accepted in October 1911 but within a year the landowners

had sold their interest to nominees of the Underground Railways (owners

of the District Railway). Accepting the situation, the LSW joined with

the District in preparing a Parliamentary Bill to increase the capacity of

31

Morden Station and forecourt in June 1927

Mitcham Junction Station c.1905 (post card by R J Johns)

(London Regional Transport) “for Mitcham, Morden & Wimbledon”

11

30

platform. Luggage for main line trains had to be loaded on the roof and

tied down with tarpaulins. Parcels were put in lockers underneath the

seats of the carriages (and) a parcel or two often went beyond its

destination… We have to thank our officials and ‘The Times’ for

providing us with such vans as we have now (1890), for they are a

luxury to those in use (in 1858)”. The last remark refers to improvements

which followed an accident on the LSW near Wimbledon. In May

1858 a guard named Baker was killed when he fell from his roof seat.

Hitherto brake blocks were held on the wheels with a connecting rod

running up to the guard’s roof seat. The coroner’s jury recommended

that brakes should be operated from inside the coach and the Board of

Trade responded to public criticisms and adopted the recommendation.

platform. Luggage for main line trains had to be loaded on the roof and

tied down with tarpaulins. Parcels were put in lockers underneath the

seats of the carriages (and) a parcel or two often went beyond its

destination… We have to thank our officials and ‘The Times’ for

providing us with such vans as we have now (1890), for they are a

luxury to those in use (in 1858)”. The last remark refers to improvements

which followed an accident on the LSW near Wimbledon. In May

1858 a guard named Baker was killed when he fell from his roof seat.

Hitherto brake blocks were held on the wheels with a connecting rod

running up to the guard’s roof seat. The coroner’s jury recommended

that brakes should be operated from inside the coach and the Board of

Trade responded to public criticisms and adopted the recommendation.

Wimbledon and Croydon Railway (1855)

A prospectus for a railway from Wandsworth to Mitcham and on to

Croydon was published in September 1852, the estimates being prepared

by one of the promoters, George Parker Bidder.11 At first both the

London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSC) and LSW objected

to the scheme but the line became a pawn in a bigger dispute between

the rival companies. The LSW supported a line from Wimbledon to

Croydon, whereupon the LBSC agreed with the promoters (and

subsequently the LSW Board) that such a line should be a joint

undertaking, with the line from Wimbledon to Mitcham leased to the

LSW for £1500 per year, and the portion between Mitcham and Croydon

leased to the LBSC for £820. The original Bill was withdrawn and the

Wimbledon and Croydon Railway Act was passed on 8 July 1853 with

an authorised capital of £45,500. Before the line could be built it was

necessary to repurchase some of the land of the former SIR which had

been sold off in 1847. Engineering work started in 1854 utilising parts

of the old trackbed across Mitcham Common. The Act gave authority

for the line to cross seven highways on the level but a station or lodge

had to be provided at each public road crossing. The Board of Trade

then insisted that where turnpike roads were crossed, a bridge had to be

constructed (i.e. Morden Road and London Road, Mitcham; but this

excluded Kingston Road, Merton).

The LSW had to withdraw from the scheme as the shareholders refused

12

were made up into two-car sets with a motor fitted in one end and a

regulator control in the other. There was no communication between

the coaches but they had an open side-corridor which facilitated bell

punch ticket issuing on the train by the guard, and the stock continued

to run until September 1954. The familiar ‘2’ headcode since inception

was changed to ‘1’ from 8 May 1978. Because of the limitations of

single line working for most of the route from Merton Park, close

headways were not possible and to add to the problems there are three

level crossings in the borough, at Dundonald Road, Kingston Road,

and Beddington Lane.

An accommodation crossing gave access to the old Rutlish School Sports

field from Dorset Road and throughout the 1930s had to be specially

opened each Thursday in school term times to allow the OTC contingent

and band to march over and return later. A public footpath had to be

accommodated in the building of Beddington Lane station.

Wimbledon and Sutton Railway (1929)

In 1865 John Innes, a City property developer, arrived in Merton with a

desire to create a suburb of villas set beside tree-lined roads. The pattern

of life in the country and in London was changing. No longer were

craftsmen living in London with a workshop at the back. New firms

were being set up with the managers and clerks travelling on horsebus

or by steam train from homes in the inner suburbs. To take advantage

of these changes John and his brother James had already formed a

company in 1864 to purchase property in London and create offices.

Now, in the farm fields of Merton and southern Wimbledon they laid

out new roads – Dorset, Mostyn, Sheridan and so on – close to the

ancient parish church. A new railway line was projected with a station

for Lower Merton giving direct access to London via Merton Abbey.

John Innes saw the potential for a railway across his estate and felt that

the LBSC would want a shorter route from Sutton to the West End

which would probably pass through Merton. For twenty years he was

closely connected with all the various schemes for railways across the

estate.24 The schemes of 1883, 1888, 1890 and 1891 were for a line

connecting Wimbledon with Sutton but none received parliamentary

approval. When the Metropolitan District Railway ran trains to

29

No interconnection could take place between the differing electrical

systems, and on 9 August 1926 it was officially announced that the

central suburban lines would be changed to standardise the Southern

Railway system. Thus all future electrification was to be 750V dc at

source, 660 V at substation busbars and a nominal 600V across the

trains.

No interconnection could take place between the differing electrical

systems, and on 9 August 1926 it was officially announced that the

central suburban lines would be changed to standardise the Southern

Railway system. Thus all future electrification was to be 750V dc at

source, 660 V at substation busbars and a nominal 600V across the

trains.

22 to Wimbledon via Haydons Road. The latter service was

well patronised following electrification, winning back many passengers

from the trams operating in Haydons Road and around Tooting. On

Sundays a new service operated between Wimbledon and Victoria via

Tooting, Streatham and Brixton using the South Eastern side at Victoria

station. This started on 3 March but on 7 July 1929 the service began

using Holborn Viaduct. Only two passenger lines remained non-

electrified in the inner suburban area and both were largely within the

Merton borough – the lower loop of the Wimbledon to Tooting via Merton

Abbey and the Wimbledon to Croydon. Both Merton Abbey and Merton

Park had suffered from competition from the Morden Tube Railway

(see p.34), and this side of the TM&W finally closed to passenger traffic

on 2 March 1929. The Merton Abbey line became a long siding after

the junction at Tooting was removed. There were no signals.

The Wimbledon and Croydon service had been worked by pull/push

(motor trains15) since 1919. Plans were prepared for doubling the track

as well as electrifying, but due to financial difficulties it was decided on

26 July 1928 to electrify the existing single line at an estimated cost of

£51,700. No additional substations were required but the estimate was

exceeded by £20,000.23 The last passenger steam train ran on Saturday

5 July 1930 and the electric service began on the following day. The

rolling stock consisted of two-car sets, formerly LBSC stock, suitably

adapted for third rail direct-current operation. LBSC trailer coaches

28

to support the board’s agreement but Bidder successfully negotiated

with other promoters to complete the railway. The opening was delayed

by the Board of Trade because there were insufficient signals at junctions.

The official opening took place on 22 October 1855, but two days later

a train was derailed near Mitcham due to subsidence of the track, which

lacked fishplates, and the driver was killed. It was the intention to

provide a double track throughout, but the line was opened with a single

track and subsequently two small sections were doubled. The bridges

over the Wandle are built to accommodate two tracks, and the line crosses

the river in Morden Hall Park only a few feet above the normal level of

the river.

Bidder operated the line himself as general manager until July 1856.

Revised agreements were made between the LSW and LBSC on 21

July 1856 and 10 August 1857 whereby both railways accepted equal

participation in the line and the LBSC was given power to raise £15,000

for doubling the track.

When first opened the only stations in the area were at Wimbledon,

Mitcham and Beddington (Lane).12 Morden (Road) was added in 1857.

Two houses adjoining the line at Mitcham were adapted for use as the

station agent’s residence with a booking hall added later. Dating from

about 1800,13 it could claim, until closed in 1988, to be one of the

oldest buildings in use by a railway.

In 1854 the Crystal Palace was transferred from Hyde Park and rebuilt

at Sydenham and re-opened by Queen Victoria. Samuel Laing, chairman

of the new Crystal Palace Railway Company as well as the LBSC(184852),

had taken the lead in arranging the transfer, after the decision had

been made to dismantle it. He arranged for one train per day to work

through from Wimbledon to Crystal Palace (Low level) via West

Croydon and this through working continued until 1928.

A double track was provided between Wimbledon and a new station at

Lower Merton (Merton Park)14 in connection with the opening of the

Tooting, Merton and Wimbledon Railway (TM&W) via Merton Abbey.

on 1 October 1868, but it was not until 1 November 1870 that a platform

was installed for the Croydon line.

Mitcham Junction was also opened on 1 October 1868 in connection

13

with the Peckham Rye to Sutton line, opened on that day.

with the Peckham Rye to Sutton line, opened on that day.

In March 1879 the line from Mitcham to Mitcham Junction was doubled

following the laying of double track throughout for the main line service

from London Bridge to Horsham through Mitcham Junction along this

part of the Wimbledon to Croydon line. In 1967 a short section through

Mitcham station reverted to single track.

A joint committee managed the line from 1868 until 1 January 1879 when

the LBSC began negotiations to purchase the LSW holding for £28,000.

The conveyance was completed in August 1879 and the LSW were granted

running powers to Lower Merton for operating the TM&W to Streatham

via Merton Abbey.

During the early years, trains usually consisted of six four-wheeled

carriages with open thirds. From 1919 ‘motor trains’15 operated with

Stroudley tank engines and two coaches containing side corridors and

gangwayed together. The latter allowed the guard to walk through the

train and issue and collect tickets. ‘Motor trains’ operated until 5 July

1930, electric trains taking over the following day. Thereafter, on the

Southern (SR), the term ‘motor train’ ceased and such trains were referred

to as ‘push and pull’ sets until the end of steam working.

At Beddington Lane tickets were issued at the signal box, and for the

benefit of passengers joining here or at Morden Road without tickets,

guards walked through the trains and could issue bell punch tickets from

a hand rack. This continued after electrification so that suitable coaching

stock had to be found (see Electrification).

14

LSW introduced economically priced season tickets favouring the new

areas (up to 17 miles distant), for regular travellers.21 A publicity

department was set up which produced literature such as ‘Homes in the

South West Suburbs’. A new timetable was compiled although it was

Walker’s vision to make timetables unnecessary. He wanted to run a

train service so frequent that trains would depart at regular minutes

past each hour at every station.

The line from Waterloo to Kingston and beyond via Raynes Park was

electrified on 30 January 1916 and in the same year electrification was

extended to Hampton Court and Claygate which provided twelve trains

every hour between Wimbledon and Waterloo. The new services were

a great success and the number of suburban passengers almost doubled

between the beginning and end of World War I. To save the cost of

building new rolling stock electric coaches were converted from loco-

hauled bogie stock. On the LSW these were made up into three-car sets

but with no second class seats. The war held up electrification on the

LBSC which had been started in 1909. The LSW were not enthusiastic

about the jointly operated Tooting, Merton and Wimbledon services

and on 1 January 1917 these were totally withdrawn as a wartime

economy.

From 1 January 1923 fourteen railway companies were merged to form

the Southern Railway Company. The main constituents were the LSW,

LBSC, LC&D and the SE, each pursuing a different policy on

electrification. The LSW favoured using a third rail carrying 600V dc,

the LBSC were going ahead with overhead conductor wires supplying

6,600V ac whilst the SE&C was proposing to adopt a third and fourth

rail system with 3,000V dc.

With the assistance of credit from the Government through the Trade

Facilities Act of 1921 the LBSC started work on a further extension of

overhead traction from West Croydon to Sutton, which was

commissioned on 1 April 1925, and on the South Western side, the

Epsom line from Raynes Park was electrified as far as Dorking on 9

July 1925 with a third rail. (The public opening was on 12 July when

Motspur Park station was opened).

27

The Waterloo services via East Putney were electrified on 25 October

1915 and ran until 4 May 1941. Since then this line has been used only

for empty stock trains, excursions and diversions due to engineering

works, etc.

The Waterloo services via East Putney were electrified on 25 October

1915 and ran until 4 May 1941. Since then this line has been used only

for empty stock trains, excursions and diversions due to engineering

works, etc.

Between 1860 and 1890 the LSW & LBSC suburban network of steam

railways had been established with the services largely operated by 44-

2 tank engines hauling six-wheeled coaches. As the century closed,

Americans began investing in railways, especially those operating city

services suitable for electrification. A financier Charles Yerkes (18371905),

who had made a fortune with tramways and elevated railways in

Chicago, arrived in London and with the support of other American

backers began purchasing various railways and tram companies. By

March 1901 he had effective control of the District Railway and included

it in his new group – the Underground Electric Railways of London

Limited. He immediately laid plans before Parliament for electrifying

the District lines. The traction supply came from a power station built

at Lots Road, Chelsea, specifically to supply Yerkes’s London’s

Underground trains.

Meanwhile the mainline companies began to suffer competition from

the trams, when in 1903, the L.C.C. introduced them through Balham

to Tooting and elsewhere. In 1907 the London United Tramways began

services between Kingston, Raynes Park, Wimbledon, Merton and

Tooting.

Further competition came from motor buses when the London General

Omnibus Company’s services were extended into the suburbs from

1 January 1912 with a depot at Putney, and Merton depot opened

November 1913. Although the LSW had had experience of electrification

on their Waterloo and City underground service since 8 August 1898

and the LBSC on their South London line from 1 December 1909, it

was not until Herbert Walker took over as General Manager of the

LSW on 1 January 1912 that the declining suburban traffic problem

was tackled in earnest. He soon decided that it was necessary not only

to electrify the inner suburban network but also to assist the movement

of population to a new outer suburban area. From 1 January 1914 the

26

Single line train working

‘One train’ working or ‘one engine in steam’ meant that only one train

could be admitted to a single line section. A staff was provided which

was carried by the train crew and was their authority to be in that section

of the track. A second train in the same direction was not possible as

the staff was then at the other end of the section. An improvement to

this was the ‘Train Staff and Ticket’ method which enabled two trains

to follow in the same direction without waiting for the return of the staff

by a train in the reverse direction. The driver of the first train was

shown the staff and given a specially printed Ticket bearing the words

“You are authorised, after seeing the Train Staff for the section to proceed

to ——— and the Train Staff will follow.” At the end of the section the

ticket was surrendered for cancellation and secured in a box.

In 1892 an electrical train staff system devised by Webb and Thompson

was introduced by the LBSC.

Wimbledon to Epsom (1859)

As early as 1842 Joseph Locke surveyed two possible routes from

London to Epsom but recommended a single line branching off from

the LSW main line between Wimbledon and Malden. This point was

chosen so that the new line could serve Wimbledon and Merton as well

as Epsom and Ewell. The local traffic was insufficient to operate a

separate suburban service but too much to be adequately served by

long distance stopping trains.

The Epsom Bill came before Parliament in 1844 but was rejected in

favour of an extension of the L&C to Epsom (7 Vic. 29 July 1844).

Two further schemes were submitted by the LSW in 1845 and 1846 but

these were again rejected.

It was not until 1857 that a Wimbledon and Dorking Bill was put forward

by private promoters for a line between Epsom and Leatherhead but

seeking an extension to Wimbledon. The first reaction by the LSW was

to object to the proposals but when they were offered 45% of the gross

receipts in return for operating and maintaining the line, they supported

the scheme and underwrote £30,000 of the authorised capital of £70,000.

15

Dundonald Road Crossing Box 24/9/73 – Photograph by John Scrace

Junction towards Merton Abbey c. 1928

(Ref. XD.76)

Remains of original station in foreground

Wimbledon Platforms 9&10 LBSC Station 1927

Mitcham Signal Box 8/7/76 – Photograph by John Scrace Material for reconstructing platforms visible in distance on platform 10.

(Ref. XM.109)

25

16

The LSW built the WM&WM but allowed the District line running powers

to Wimbledon from their existing line at Putney Bridge, whilst retaining

the LSW’s right of running to Kensington over the District Railway. All

running expenses on the new line were to be paid by the LSW and through

fares were to be apportioned between the LSW and the District. The

successors to each company continued to operate on the same basis.

Building work was started in April 1887 by the contractors Lucas and

Aird and the most notable engineering work was the bridge over the Thames

at Putney which took two years to construct. The line opened on 3 June

1889 for District line trains only, and when the LSW began services on 1

July they ran to Waterloo via Putney Junction, and not Fulham or

Kensington. The LSW operated 21 weekday trains each way.

The LSW built the WM&WM but allowed the District line running powers

to Wimbledon from their existing line at Putney Bridge, whilst retaining

the LSW’s right of running to Kensington over the District Railway. All

running expenses on the new line were to be paid by the LSW and through

fares were to be apportioned between the LSW and the District. The

successors to each company continued to operate on the same basis.

Building work was started in April 1887 by the contractors Lucas and

Aird and the most notable engineering work was the bridge over the Thames

at Putney which took two years to construct. The line opened on 3 June

1889 for District line trains only, and when the LSW began services on 1

July they ran to Waterloo via Putney Junction, and not Fulham or

Kensington. The LSW operated 21 weekday trains each way.

The District Railway operated four-wheeled coaches, some of which were

still in use in 1900. Plans for electrifying the line were made in 1902 (2

Edw. 7. Pt. 3) and this involved laying third and fourth rails, as conductors,

over the LSW track from Putney Bridge to Wimbledon. District line

electrified services commenced on 27 August 1905 through to Wimbledon

but were often delayed thereafter by the presence of LSW steam trains

operating the Waterloo services.

In 1911 the LSW proposed additional tracks from Wimbledon to East

Putney to segregate District trains from their own services into Waterloo.

This was the Metropolitan and District Bill and incorporated a renewal

of LSW running powers into High Street or South Kensington. The Act

was passed on 17 August 1912 but the problem of integrating the LSW

third rail only electrification with the Underground’s fourth rail negative

return had been resolved20 and the duplication of tracks found unnecessary.

The LSW went ahead with its suburban electrification which included

the Wimbledon to Waterloo via East Putney. Meanwhile World War I

intervened to shatter the LSW’s dream of running trains to the West End

and no LSW train has ever crossed its own river bridge at Putney, other

than departmental trains for repairing the track, etc.

24

The Bill received Parliamentary approval on 27 July 1857. Thomas

Brassey built the double tracked line but encountered delays caused by

weather, men and shortage of materials, and it was not until 4 April

1859 that the line opened to Epsom with stations at Worcester Park16

and Ewell. At the Wimbledon end, the double track used the main line

for a mile and ran into platforms which, at that time, were on the west

side of Wimbledon Bridge.

In the spring of 1860, the LSW decided to purchase the Wimbledon and

Dorking Company (W&D) and offered £40,000 in shares plus £43,000

cash towards outstanding debts. The offer was rejected and the W&D

obtained powers to increase their capital to ease their cash problems.

This meant that the LSW would have reduced voting power and in

August 1860 they promptly sought an injunction to delay the issue.

The W&D then agreed that the new issue would have no voting rights,

and talks between the two companies ended with the LSW agreeing to

subscribe its allocation of the new shares plus £48,000 cash towards

debts. The LSW then acquired the railway by offering LSW 4½%

preferential stock to W&D shareholders.

Tooting, Merton and Wimbledon Railway (1868)

In 1860 the London Chatham and Dover Railway (LC&D) obtained

authority for a line from Beckenham via Herne Hill, Blackfriars Bridge

to Ludgate Hill. All railways desired access to the City and the LC&D

was the first of the railways serving towns south of the Thames to

achieve this. At that time the LSW arranged for all its main line trains

into Waterloo to have omnibuses in attendance to convey passengers to

the City and to avoid this they approached the LC&D suggesting two

connections with their proposed line. The first was a line from Clapham

Junction and the second from Wimbledon via Merton and Tooting. Both

routes merged at Loughborough Junction. The LC&D welcomed the

connections and the financial support for constructing the Ludgate Hill

line (£316,000 for permanent LSW running powers). In 1863 the LBSC

obtained an Act to link Streatham with Sutton as well as a line from

Streatham to Tooting. On 29 July 1864 the Tooting, Merton and

Wimbledon Railway Act was passed (27 and 28 Vic. cap. 325), promoted

as an independent company. It involved two lines from Wimbledon to

17

Tooting – one from the W&C at Lower Merton and one from Wimbledon

station via Hayden’s Lane.

Tooting – one from the W&C at Lower Merton and one from Wimbledon

station via Hayden’s Lane. From Tooting a line joined the LBSC at

Streatham. Engineering work commenced early in 1865, the engineer

being W. Jacomb with Aird and Son as contractors. The LSW and

LBSC agreed to finance the scheme jointly and a further Act was obtained

on 5 July 1865 (28 and 29 Vic. cap. 273) giving the two companies

power to acquire and manage the line jointly. This Act also authorised

the essential mile and a half of line from Streatham to Knights Hill

(Tulse Hill) which would enable the LSW to reach their coveted second

access to Ludgate Hill. By May 1867 this connection had still not been

completed by the LBSC which caused the LSW some annoyance. The

TM&W finally opened on 1 October 1868 with LBSC trains on the

Merton Abbey loop and on the same day they began services on the

Peckham Rye to Sutton via Mitcham Junction route. It was not until

1 January 1869 that the other loop line via Hayden’s Lane was opened.

The LSW operated trains from Wimbledon to Ludgate Hill (in connection

with the Kingston line – see p.22) and the LBSC to London Bridge and

both companies served either side of the loop. This enabled trains to

run forward at Wimbledon on to the alternate loop without reversing

engines and avoiding train crew lay over time. Because of its shape on

a map the loop became known as ‘the Pear'(see map on p.21). The

route was double tracked throughout which meant doubling the portion

on the W&C from Wimbledon to Lower Merton. The doubling meant

a change in alignment between Kingswood Road and Wimbledon Station.

The LBSC platform had been rebuilt east of Wimbledon Bridge,18

allowing a shorter curve for the double track closer to Wimbledon station.

The curve of the previous single line may be traced on early O.S. maps

and follows the public footpath to Dundonald Road.

In 1878 the LBSC acquired the sole rights in the railway but it remained

in joint management until the amalgamation of railways in 1923.

The LSW always experienced operating difficulties on their route where

the trains had to be accommodated on LBSC metals between Streatham

Junction and Tulse Hill and the LC&D lines between Tulse Hill and

Ludgate Hill. The LSW operated thirteen trains a day in each direction,

of which two ran through to Kingston, and the LBSC operated fifteen

trains on their routes but there was no Sunday service. The LBSC also

18

10 August 1882 and the existing abutments indicate that provision was

made for a fifth track on the main line. A new up platform and booking

office was necessary at Raynes Park on the north side and all changes were

effected on Sunday 16 March 1884 when the up Epsom trains called at the

new platform at Raynes Park and used the up main track through

Wimbledon. Finally, on Sunday 30 March, the quadrupling of the main

line to Hampton Court Junction was completed and the layout became up

local, up through, down through, down local, and this has remained so,

west of Gap Road bridge.

Wimbledon, Merton and West Metropolitan (1889)

Following the passing of the Kingston & London Railway (K&L) Bill on

22 August 1881 (44 and 45 Vic. cap. 212), the Common Conservators as

well as many Wimbledon residents were displeased for various reasons.

Some thought that Wimbledon village never would have an adequate railway

and decided to sponsor their own Bill assisted by Col. A.L. Cole. This was

an ambitious scheme from Wimbledon (LSW) northwards, but east of the

Common and Hill towards Wandsworth where it would join the proposed

K&L line. The promoters also sought running powers to South Kensington

and High Street (District), to Addison Road Kensington (West London

Extension), to Leatherhead via Epsom (LSW), to Surbiton (LSW), to

Streatham (TM&W), and to Croydon (W&C).

After a mauling in both Houses of Parliament, the WM&WM Bill received

Royal Assent on 18 August 1882. No running powers were allowed over

the LSW except over a spur towards the TM&W and no running powers to

Streatham or Croydon. Conversely the LSW were refused running powers

over the WM&WM. The route was also changed but still made a connection

with the K&L. It suffered therefore from the delay in the construction of

that line. Frustration built up as each year passed until in the Autumn of

1885 the promoters of WM&WM sought parliamentary powers to force

the LSW and the District line to build the K&L. In November, the LSW

offered the promoters £10,500 and asked to take over their powers. This

was accepted after safeguarding their contractors, Lucas and Aird; obtaining

recompense for their Parliamentary deposit and other stipulations.

Arrangements were confirmed by the LSW Act of 25 June 1886 which

allowed the abandonment of most of the K&L line and for a diversion of

the WM&WM through Wimbledon to a terminus west of the station.

23

Kingston to Wimbledon (1869)

Kingston to Wimbledon (1869)

LSW main line changes

At the request of Richard Garth, lord of the manor of Morden, a station

was provided in west Wimbledon, although within the parish of Merton.

This was opened on 30 October 1871 and called ‘Raynes Park’ because

both the main line and the Epsom branch crossed the farming lands of

West Barnes Park once owned by Edward Rayne (d. 1847). The platform

and station buildings were only provided on the south side of the main

line with one face of the platform serving the Epsom line and the other

the Kingston services.

On 22 August 1881 an authorising Act was secured to allow the LSW

main line to be quadrupled as far as Surbiton, but between Wimbledon

and Malden this merely meant a re-arrangement of the existing four

tracks (up main, down main, up local and down local). Platform changes

were necessary at Wimbledon and the station was rebuilt on the east

side of Wimbledon Bridge, and opened on 21 November 1881. From

Sunday 25 March 1883 the up Kingston trains were diverted by means

of a new single line from the Kingston branch at Malden and arrived at

Wimbledon on the up main line. Two new tracks were laid from Clapham

Junction to Wimbledon, entering the borough on a widened bridge over

the river Wandle and coming into use on 2 March 1884. At the same

time a road overbridge replaced the level crossing at Merton Road (now

Durnsford Road). At Raynes Park other major changes had to be made.

In order to bring the Epsom up track on to the north side of the main

line a wide diversion had to be made with a ‘dive under’ beneath the

main line. Authority for the new line and ‘dive under’ was obtained on

22

later ran ‘push and pull’ trains 15 between Streatham and Wimbledon.

By 1910 both services were suffering from competition by electrified

tramways and as a wartime economy to save fuel supplies, passenger

services on both lines were withdrawn on 1 January 1917. It was not

until 27 August 1923 that services were restored as part of a deal with

the Underground Railway over the Wimbledon to Sutton line (see page

33). In October 1923 two-coach ‘push and pull’ working was introduced

serving Streatham or Tulse Hill via both Haydons Road and Merton

Park with 20 through services to London Bridge and four to Ludgate

Hill.19

In 1926 the Underground extension to Morden was opened offering a

better service to London, which meant that Colliers Wood took away

the passengers which had used Merton Abbey and South Wimbledon

took those from Merton Park. This side of the loop was therefore closed

to passenger traffic on 2 March 1929.

The junction at Tooting was severed on 10 March 1934.

Peckham Rye to Sutton Railway (1868)

The LBSC obtained powers in 1863 to construct a line from New Cross

to Sutton intersecting the Wimbledon and Croydon line near Mitcham

Common. The original intention was for the new line to pass over at

right angles with a station at the bridge near the Croydon Road, but

local opposition forced the line to skirt the north of Mitcham Common

thus meeting the Wimbledon line obliquely. A junction was therefore