01 The Cricket Green

Mitcham Histories 1

Mitcham Histories 1

by Eric Montague

The unique character of Mitcham’s Lower Green, the eastern half of which is today known as the Cricket Green, was recognised by its declaration as a Conservation Area by the London Borough of Merton in 1969. The Green was formerly part of the expanse of largely uncultivated heath and woodland – the common ‘waste’ – which formed a substantial part of the parish throughout the Middle Ages.

By the time of the Norman Conquest, still forming part of an unbroken swathe of rough grazing land extending from today’s Church Road eastwards as far as Commonside East, the Lower Green served to separate the two Saxon ‘vills’ of ‘Witford’ and ‘Michelham’ recorded in the Domesday Survey.

Both sanctioned and unauthorised enclosures of land on the margins of the Green have diminished its extent, but a little over eight acres (3.25 ha) survive today as public recreational space. It is conceivable that here, in the Middle Ages, stood the archery butts, close by Mitcham’s earliest recorded inn, the White Hart. Skilled bowmen may no longer be needed for the defence of England, but since the late 17th century the Lower Green has been the cradle of another sport whose stalwarts were able during the great days of village cricket to throw down a challenge to all comers, including visiting Australians.

The gradual development of the land peripheral to the Green has left an interesting history of building and rebuilding, as well as a legacy of architectural styles which, although modified in their translation to a village setting, nevertheless reflect trends and fashions throughout the Home Counties.

- THE CRICKET GREEN: The Heritage of Cricket; The Village Playground

- THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL

- THE BURN BULLOCK (FORMERLY THE KING’S HEAD)

- THE TATE FAMILY

- THE TATE ALMSHOUSES

- MITCHAM’S FIRST PRIMARY SCHOOL

- THE METHODIST CHURCH

- ELM LODGE

- MITCHAM COURT

- THE WHITE HOUSE (FORMERLY RAMORNIE) No 7 CRICKET GREEN

- OTHER BUILDINGS AROUND THE GREEN: The Eastern Side of the Green; Sir Isaac Wilson and The Cumberland Hospital; Chestnut Cottage; The Western Side of the Green

APPENDIX: POLICING OLD MITCHAM

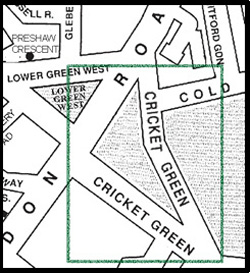

Detail from the First Edition Ordnance Survey Map, published in 1816,

showing the village of Mitcham

MITCHAM HISTORIES: 1

THE

CRICKET

GREEN

E N MONTAGUE

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

THE CRICKET GREEN

Published by

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

2001

© E N Montague 2001

ISBN 1 903899 00 1

Printed by Intype London Ltd

Cover Illustration: “Alms-Houses at Mitcham, Surrey

Built and endowed by Miss Tate AD 1829”

(Engraving published in the Gentleman’s Magazine March 1830)

INTRODUCTION

The unique character of Mitcham’s Lower Green, the eastern half of which is

today known as the Cricket Green, was recognised by its declaration as a

Conservation Area by the London Borough of Merton in 1969. The Green

was formerly part of the expanse of largely uncultivated heath and woodland

-the common ‘waste’ – which formed a substantial part of the parish throughout

the Middle Ages.

By the time of the Norman Conquest, still forming part of an unbroken swathe

of rough grazing land extending from today’s Church Road eastwards as far as

Commonside East, the Lower Green served to separate the two Saxon “vills”

of “Witford” and “Michelham” recorded in the Domesday Survey.

Both sanctioned and unauthorised enclosures of land on the margins of the

Green have diminished its extent, but a little over eight acres (3.25 ha) survive

today as public recreational space. It is conceivable that here, in the Middle

Ages, stood the archery butts, close by Mitcham’s earliest recorded inn, the

White Hart. Skilled bowmen may no longer be needed for the defence of

England, but since the late 17th century the Lower Green has been the cradle

of another sport whose stalwarts were able during the great days of village

cricket to throw down a challenge to all comers, including visiting Australians.

The gradual development of the land peripheral to the Green has left an

interesting history of building and rebuilding, as well as a legacy of

architectural styles which, although modified in their translation to a village

setting, nevertheless reflect trends and fashions throughout the Home

Counties.

This, the first volume in a series which, it is intended, will eventually cover the

whole of the former Borough of Mitcham, reproduces in extended form three

articles (on Mitcham Court, Elm Lodge and the National Primary School) written

for the Merton Borough News in 1972, and which were published that year in

the paper’s “Merton Story” series. The choice of illustrations and maps used

has been dictated largely by the availability of originals either in my possession

or in the Local History Collection at Merton Local Studies Centre. It is hoped

they will prove an adequate accompaniment to the text.

E N M Sutton, January 2001

vi THE CRICKET GREEN

The Cricket Green (Lower Green East)

Detail from the Second Edition 1894 Ordnance Survey map

vii

Scale: 25.344 inches to a Statute Mile

THE CRICKET GREEN

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A study such as this would have been impossible without help from

many sources. Publication, bringing together the results of research

over a period of some 35 years, now affords me the opportunity to

acknowledge the very great debt of gratitude I owe, in particular to

staff past and present of Mitcham reference library (now incorporated

in Merton Local Studies Centre), the former Surrey Record Office at

Kingston, the Minet Library at Lambeth, the library of Surrey

Archaeological Society and the Surrey History Centre at Woking. Over

the years I have come to regard many of them as personal friends. I

would also like to thank my wife for so patiently reading and correcting

early drafts almost ad nauseam and, last but by no means least,

members of the editorial panel of Merton Historical Society without

whose encouragement, invaluable advice and comments I would never

have had the confidence to offer this little book to a wider readership.

E.N.M.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii

MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS x

1 THE CRICKET GREEN 1

The Heritage of Cricket 7

The Village Playground 12

2 THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL 17

3 THE BURN BULLOCK (FORMERLY THE

KING’S HEAD) 29

4 THE TATE FAMILY 41

5 THE TATE ALMSHOUSES 51

6 MITCHAM’S FIRST PRIMARY SCHOOL 57

7 THE METHODIST CHURCH 61

John Wesley’s Visits to Mitcham 61

The Early Methodist Society 63

The Cricket Green Church 66

8 ELM LODGE 69

9 MITCHAM COURT 75

10 THE WHITE HOUSE (FORMERLY RAMORNIE)

No 7 CRICKET GREEN 85

11 OTHER BUILDINGS AROUND THE GREEN 93

Introduction 93

The Eastern Side of the Green 94

Sir Isaac Wilson and The Cumberland Hospital 95

Chestnut Cottage 98

The Western Side of the Green 107

APPENDIX: POLICING OLD MITCHAM 118

NOTES AND REFERENCES 122

INDEX 136

THE CRICKET GREEN

MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

“Alms-Houses at Mitcham, Surrey, Built and endowed by

Miss Tate AD 1829” (Gentleman’s Magazine March 1830) Cover

Detail from the 1816 OS Map, showing the village of Mitcham i

ii

The Cricket Green: detail from the 1894 OS Map vi

A match in progress on the Cricket Green, c1931 3

Cricket on the Green, c1975 6

Costumed participants in an Elizabethan Pageant, 1911 13

The White House, Chestnut Cottage and Victorian villas 16

Vestry Hall and Cricket Green from The King’s Head, c1905 28

Plan of King’s Head, National School and Almshouses, 1888 30

The King’s Head Hotel seen in an Edwardian postcard 35

Side view of the Burn Bullock, 1993 35

“North East View of an Old Mansion at Mitcham”,1827 40

“The Recovery: A House for Lunatics, Mitcham Green”, 1825 40

The Tate Almshouses, Lower Green, c1976 55

The houses built in 1838 for the National Infants School, 1972 60

Mitcham’s first Methodist chapel, No 46 Lower Green, 1993 65

Celebrations on Lower Green, 1887 66

Elm Lodge, 1972 73

Mitcham Court, 1972 74

The White House, No 7 Cricket Green, 1972 86

Chestnut Cottage, No 9 Cricket Green, 1972 99

View of the ‘Causeway’, Lower Green, c1905 106

Houses overlooking Lower Green, 1993 111

The former Britannia public house, Lower Green, 1993 113

Greenview and Mitcham Cricket Clubhouse, c1910. 114

The last of the Cricket Green elms, 1967 117

Mitcham’s first Police Station, erected 1885 119

Chapter 1

THE CRICKET GREEN

It is now some 70 years since the last of the countryside which once

surrounded Mitcham disappeared under housing estates, and the town

was finally engulfed by the relentless expansion of London’s suburbia.

Fortunately, however, Mitcham retains its two village greens – the Upper

or Fair Green, and the much larger and more attractive Lower Green,

the eastern half of which is usually called the Cricket Green. Whereas

the first was sometimes referred to more specifically in the 19th century

as Upper Mitcham Green, the latter was also known as Whitford Green.

The origins of both must lie in pre-Conquest England, when they were

contiguous parts of the extensive Mitcham Heath extending far to the

south and south-east, where it merged into the waste or commons of

the neighbouring parishes of Beddington and Croydon.

It is clear that when the Domesday Survey was conducted in 1086 two

distinct settlements or ‘vills’ were recognised in Mitcham – “Michelham”

and “Witford”.1 Wicford or Whitford, as it was rendered at various

times, was absorbed within the emerging ecclesiastical parish of Mitcham

by the 13th century, eventually losing its separate identity during the

later Middle Ages as it merged with its larger neighbour. Certainly by

Tudor times Whitford, or Lower Mitcham, formed part of the

administrative parish of Mitcham for poor law, highway and most other

local government purposes. Although the two halves of the Green,

lying either side of the London Road, were often known jointly as Lower

Mitcham Green by the middle of the 18th century, such is the

extraordinary persistence of folk memory that the Cricket Green, or

eastern portion, continued to be described as “Whitford Green” until

well into the 19th century.2

The names of the two vills are Anglo-Saxon, but archaeological evidence

from a number of sites points to settlement having been widespread

throughout the district during the 1st to 4th centuries AD.3 Significantly,

the large Dark Age cemetery excavated at Ravensbury early last century

contained Romano-British as well as early Saxon material, hinting at

continuity of the community into the post-Roman period. By the early

8th century Micham – the prefix micmeans large – began to find mention

in records of Chertsey Abbey.4

THE CRICKET GREEN

In “Wicford” – the place-name throughout the Middle Ages was written

with either c or k – we may detect the place-name element Wic, from

the Latinvicus, meaning a place or settlement. We need look no further

than the Wandle crossing upstream from Mitcham bridge for the ford,

and the community it served was obviously nearby. This was the way

to Sutton, and commonsense tells us the ford must be of respectable

antiquity, but “Witford” remained absent from the documentary record

until the 11th century.5

In Mitcham there is archaeological evidence for later Saxon and early

medieval occupation both sides of Church Road from the vicinity of the

parish church to the commencement of the Lower Green,6 but so far

nothing has been found to indicate when the first dwellings were erected

around the Cricket Green itself. A primary grouping of houses and

cottages where the roads meet might be expected, an idea to which

support is given by the earliest surviving maps of the area, showing a

marked concentration of buildings near the White Hart and Burn Bullock

inns.7 Both these hostelries can be traced back to the beginning of the

17th century, but unfortunately the maps only date from the mid-18th

century, and are thus relatively late. Other groups of dwellings are

shown along the eastern and south-eastern margins of the Cricket

Green. The sites they occupy are small, and demolition of the original

structures, together with a lack of good photographs of those surviving

into the 19th century, means we have nothing to indicate their date of

erection. Some of these plots probably originated as unauthorised

enclosures of waste ground taken for house building by squatters either

during the Middle Ages, or periods when the exercise of manorial

jurisdiction was lax. That the process of unsanctioned enclosure was

still taking place in the late 18th century is shown by a surveyor’s report

in 1806 to the dean and chapter of Canterbury, who then held the lordship

of the manor of Vauxhall and exercised jurisdiction over the Cricket

Green.8

What was probably at one time the south-western boundary of Whitford

Green can be detected in the tithe map of 1847 and the first edition 25inch

OS map of 1867. Here the rear fences of properties facing the

southern tip of the Green all follow a common boundary, defined by an

ancient ditch taking water from slightly higher ground to the south

THE CRICKET GREEN

east. Long ago the ditch was piped or confined in an underground

culvert to become a surface water sewer, but here and there it survived

as a visible feature in the 19th century, and can still be discovered near

Mitcham Garden Village. The south-eastern portion of the Green is

relatively low lying and in the past, when the water table in the underlying

gravel was higher than it is today, this corner tended to be marshy. A

century ago land drains were laid beneath the Cricket Green itself to

improve the drainage, and from the old name for the road along the

southwestern side of the Green – The Causeway – it is obvious that at

some time the level of the road was raised above the water-logged

ground either side.

By the nature of their sites, therefore, we can expect the dwellings

overlooking much of the southern tip of the Cricket Green to have been

generally humble in character. Nearer the London Road, however,

possibly because of better drainage, the situation evidently improved

and, as we shall see in later chapters, it was here that a large house and

a farm were to be found by the 17th century.

A match in progress on the Cricket Green (Post card, c1931)

THE CRICKET GREEN

Another group of dwellings, perhaps a little later in origin, can be seen

along the eastern side of the Green. On the evidence of the deeds, one

at least, No 9 Cricket Green, had been built on land falling within the

jurisdiction of the manor of Ravensbury. As in the case of enclosures

on the south-eastern side of the Green, between Jeppos Lane and the

Cranmers, there seems to have been observance of a recognised

boundary to the rear, and the house plots in general lack depth, showing

that they too were confined to a narrow strip of waste at the edge of the

Green. This can be seen clearly in a plan of the Cranmer estate produced

for Mrs Esther Maria Cranmer in 1815,9 and also in the tithe map of

1847. Behind the house plots on the eastern margin of the Green were

the large rectangular enclosures of meadowland belonging to the grounds

of Park Place. In the 14th century part of this estate was referred to as

“Allmannesland” – literally “all men’s land” – and had evidently once

been enclosed from the broad swathe of common grazing land extending

from the Lower Green to Three Kings Piece. While the population of

Mitcham remained small, and the heath seemingly limitless, the practice

of enclosure or ‘assarting’ waste land was obviously acceptable, and

there is a record from the 12th century of the parishioners of Mitcham

actually making a gift of common waste to the newly founded priory of

St Mary at Southwark.10 Today this can be identified as the land

occupied by the Canons Leisure Centre and its adjacent parkland, lying

between Park Place and the southern corner of the Cricket Green.

In the main, the common lands of Mitcham, so important in the medieval

economy for the pasturage of stock and as a source of fuel, largely

escaped formal enclosure during the agricultural revolution of the 18th

and early 19th centuries, and 522 acres (211 ha) survive today as public

open space. Management of the largest portion, some 460 acres (186

ha) in extent and comprising Mitcham Common, became the responsibility

of a Board of Conservators in 1891.11 Five scattered fragments – Figges

Marsh, the Upper Green, Three Kings Piece, Cranmer Green and the

Lower Green – were vested in the Urban District Council of Mitcham

following the passing of a Private Act in 1923.12 They are now managed

by the London Borough of Merton.

The eight and a half acres (3.4 ha) of the Lower Green comprised part

of a large estate or tithing in Mitcham within the jurisdiction of the manor

THE CRICKET GREEN

of Vauxhall which, since the 14th century, was held by the Cathedral

Church of Christ at Canterbury. When the Dissolution of the great

monastic houses took place between 1538 and 1540 the monastery of

Canterbury was abolished, and the prior and convent were replaced by

a secular chapter headed by a dean. The Lower Green and several

houses overlooking the Cricket Green remained within the jurisdiction

of Vauxhall until the close of the 19th century, by which time lordship of

the manor had passed to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. The history

of the manor, the origins of which can be traced back to a Saxon estate,

is the subject of the next chapter.

The dean and chapter of Canterbury were to prove worthy guardians

of what the court rolls refer to as “the Common called the Green”,

resisting unauthorised enclosure and only sparingly granting permission

to the parish officers to use the land for civic purposes. Courts baron

and leet continued to be held held regularly throughout the 19th century,

with the time-honoured writ of seisin and the swearing of an oath of

fealty remaining part of the quaint ritual attaching to the admission of a

new property owner to the tenancy of the manor.13

Until the closing years of the 19th century rights of grazing on the

common wastes remained of economic importance to copyholders of

the four Mitcham manors, and were jealously defended by those with or

without legitimate claims. One such was Ebenezer Thompson an old

dairyman, who regularly turned his cattle out on the southern part of

the Green, as well as on Three Kings Piece.14 Although it may not

always have been appreciated, tenants of the manor of Vauxhall and the

residents of Mitcham as a whole had cause to be grateful to the vigilance

shown by the dean and chapter in their control of the Lower Green.

The manor pound near the site of the Cricketers was still in use during

the early 19th century to hold livestock found grazing without authority,

and old photographs show that horses and donkeys, in addition to cattle,

were to be seen on the Green until shortly before the Great War.

Prior to the transfer of the greens to the Urban District Council in April

1924, control over the Cricket Green was exercised by the Board of

Conservators under the Metropolitan Commons (Mitcham)

Supplemental Act 1891. Proceeding under byelaws which they were

THE CRICKET GREEN

empowered to adopt under the new legislation, the Conservators

succeeded, not without recourse to the courts in the case of one grazier

from Beddington Lane, in abolishing all grazing on the Common. Of

this action there was probably general approval, but at times the

Conservators seem to have acted somewhat insensitively and without

over much concern for the strength of local feeling. Children, for

instance, were barred from playing on one corner of the Green, probably

to avoid annoyance to residents such as Harry Mallaby-Deeley of

Mitcham Court, who was chairman of the Board. When in the 1890s

Liberal George Pitt, a retired shopkeeper and local eccentric, sought to

assert the rights of ‘the common man’ by engaging a band to play on

the Green on the occasion of his son’s coming of age, proceedings

were instituted against him in the courts. As is so often the case in

such disputes, local opinion polarised between those who supported the

‘have-nots’ and the more affluent members of the community with an

interest in preserving the “tone” of the neighbourhood and safeguarding

property values.

Cricket on the Green

(Photograph taken from the balcony of the Clubhouse in about 1975)

THE CRICKET GREEN

The northern part of the Cricket Green is still crossed by a remarkable

survival from early medieval times in the form of a footpath leading

from houses in the vicinity of the parish church to what was once the

unfenced East Field, cultivated in strip holdings by the villagers. This

ancient track, a mile long, runs from Church Road and crosses Lower

Green West and the Cricket Green before becoming the footpath ‘Cold

Blows’ leading to Commonside West. From here it traverses Three

Kings Piece before becoming in turn Lavender Walk and Gaston Road.

The path passes over the railway by a footbridge erected by the London

Brighton and South Coast Railway Company in 1868, and reaches its

destination as Acacia Road. The attempt a century or so ago to rename

Cold Blows St Mary’s Avenue evidently met with little support from

the ordinary folk of Mitcham, and its ancient name is now officially

recognised.

Until the end of the 19th century there were several other paths crossing

the Cricket Green, including one from the corner opposite the White

Hart to the beginning of Cold Blows Lane, and another from the Vestry

Hall to the police station. At least one village diehard, determined to

assert his ‘rights’, used to make a practice of walking across the Green

during cricket matches, to the understandable annoyance of both players

and spectators. There was another character who, to make a point,

rode his horse across the Green, but he was taken before the Croydon

Court and convicted.15

Obviously from the cricketers’ point of view these paths could not be

tolerated, and with increasing pressure from an expanding population

making some form of protection necessary, railings were erected around

the Green in about 1905. A solitary path now crossing the southern

part of the Cricket Green in front of the almshouses skirts the cricket

field. It is shown on the OS map of 1867, but its origin is unknown.

The Heritage of Cricket

With the exception of Broadhalfpenny Down near Hambledon, the

Cricket Green at Mitcham has the distinction of being possibly the most

famous village cricket ground in the world. It is our misfortune that

many of the earlier records of the Mitcham Cricket Club were lost in a

THE CRICKET GREEN

fire at the pavilion during the 1939-45 War. The Hambledon Club may

thus be able to claim seniority, but from a reference to the game being

played at Mitcham in 1685, it is apparent that cricket has been established

here for well over 300 years.16

As long ago as 1707 Mitcham boasted so many good players it could

afford to throw down the gauntlet to London, and one of the earliest

accounts of a game on Mitcham Green comes from The County Journal

of June 26th 1730, which reported a “Great cricket match which was

played between the Gentlemen of London and those of Mecham in

Surrey.” Scores in those days were kept by the primitive method of

cutting notches on a stick, andThe County Journal commented that on

this occasion the game was won by the gentlemen of London “by a

considerable number of notches.” Despite this defeat, the cricketing

giants of “Mecham” remained virtually unbeatable, and throughout the

18th century their Green was considered amongst the best in the whole

of Surrey.17 The headquarters of Mitcham cricket club in the late 18th

century was the Swan, the inn then standing on the site of the present

Cricketers. It was kept by Samuel Sanders, and when in 1799, following

his death, an inventory was prepared of his goods and chattels, a framed

picture entitled The Cricketers was found in the bar. There were also a

parcel of old books and scoring slates, three “crickett” balls, 13 “Crickett

and Trap balls”, three “Trap Batts”, and two “Tressell” tables and

benches, whilst in the “Club Room” there was a “Marquee”.18

During the brief period between 1801 and 1805 when Nelson was able

to savour life as a country gentleman, he is said to have enjoyed driving

over to Mitcham from Merton to watch the cricket. Years after

Nelson’s death the older villagers loved to recall how, on one occasion

when he was accompanied by Lady Hamilton, the great man gave a

group of lads a shilling “to drink to the confusion of the French”. Mitcham

remained the strongest village side in the County throughout the

Napoleonic wars, and when Surrey played England at Lord’s in 1810

no fewer than five of the County side were Mitcham men. For the

next century Mitcham Green was to be a veritable cradle of cricket,

with a host of celebrities learning to play here. The names of many are

now forgotten, but the memory of others is revered by lovers of the

game. Dan Hayward was born in Mitcham in 1808 and played for the

THE CRICKET GREEN

Mitcham team long before he went to Cambridge. His contemporaries

included Thomas Sewell, Tom Sherman (at one period honorary treasurer

to the village club), Thomas Lockyer, William Gaffyn (who lived to be

100), John Bowyer and later James Southerton, the famous England,

Sussex, Hants and Surrey bowler. For a while Southerton was mine

host of the Cricketers inn, which provided dressing rooms for the club

before the present pavilion was built next to the King’s Head.

The picturesque appearance of the game on the Green “before overarm

bowling came into practice” can be visualised from an old resident’s

recollections of a match in the 1830s in which the eleven on one side

wore high beaver hats, white cord breeches, silk stockings and buckle

shoes. “Their skill and play were quite equal to that of the present

day”, he recalled some fifty years later.19 Another, writing of the 1860s,

said that it was not unusual to see players in top hats. “They may not

have made their centuries, but when one considers the remarkable fielding

displayed by those very alert gentlemen, one wonders at times whether,

if equal agility was displayed in fielding today” (the 1940s) “such

extraordinary scores would be made. A top hat was not always the sign

of inactivity.”20

Towards the middle of the century, playing for side-stakes became

commonplace and bets were made freely on the ground. It has been

alleged, perhaps with some exaggeration, that players (not only in

Mitcham) were offered and took bribes to lose, and that gangs of bookmaker’s

‘legs’ dominated the game to such an extent that on occasions

both teams were bribed to lose, and to win became a farce.15 Undoubtedly

during the early part of the 19th century ‘sporting games’ were organised

by the gentry for big stakes, and in one notable game arranged by two

noblemen at Balls Pond, Middlesex, in 1811, two elevens of ‘females’,

representing Hampshire and Surrey, played a game for 500 guineas a

side. The Hampshire XI was victorious. Until recently a poster survived

in the possession of Mitcham Cricket Club advertising “A Grand Match

of Cricket” which took place on the Green on Monday, July 26th 1819,

between ten gentlemen of Mitcham and William Dyer Esq, of Blackheath,

and ten gentlemen of Dorking with Mr Jupp of Reigate, for 100 guineas

a side. This match was typical of many arranged during the first half of

the last century.

THE CRICKET GREEN

Charles H Hoare, grandson of Henry Hoare of Mitcham Grove and a

member of the famous banking family, came to live at the Canons in

about 1850. He played for Surrey between 1846 and 1853, and was

treasurer of the County Club for several years. With his keen support,

and that of C T Hoare his son, Mitcham Village Club flourished. T P

Harvey, generally esteemed in his day as one of the finest all-rounders

the game had produced, was captain for about 20 years. Other

outstanding local players towards the turn of the century included A

Ferrier-Clarke, G Jones and William Wright Thompson (captain and

also honorary secretary of the village club) who before World War I

was managing director of R R Whitehead Bros Ltd, the felt

manufacturers at Mitcham. All three played for Surrey. Still later,

Mitcham boasted such great players as Tom Richardson, the Surrey

fast bowler, Herbert Strudwick who kept wicket for the county, and

Andrew Sandham who was long remembered for the centuries he

scored for Surrey in the mid-’thirties. Without question, these three

were the finest cricketers that Mitcham produced, and each achieved

international fame, playing for England on many occasions.

Contemporaries who earned Surrey caps included J Keens, F Pearson,

B Sullivan, and E Bale, and there have been many others too numerous

to mention down to the present day.

With such a tradition, and the inspiration offered to local youths, it is not

surprising that Mitcham Green became a training ground for cricket,

and on fine summer days towards the end of the Victorian era seemingly

every corner was being taken by players of all ages and proficiency.

Tom Francis, a keen cricketer himself, used to recall in his lantern slide

lectures that it was not at all unusual to witness three cricket matches

being played on the Green simultaneously,20 and Emma Bartley observed

in her memories of Mitcham during the 19th century that “on cricket

match days there were generally five marquees erected for the

occasion.” Such was the enthusiasm for the national game that in

those days, when long hours in the local shops and factories meant

young cricketing buffs found their playing time severely limited, matches

were arranged starting at dawn, drawing stumps at 7.30 or 8 am. One

notable match took place in the summer of 1870 between “The Upper

Mitcham Early Risers” and the “Lower Mitcham Peep-o’-Day Boys”.

THE CRICKET GREEN

More often than not the younger set would be followed by players

from the “Old Buffer’s Club”, whose headquarters was the old Britannia

inn, now a private house, 40 Cricket Green. The “Old Buffer” was the

pen-name of Fred Gale of the Croft, Commonside East, a celebrated

cricketing writer who did much for Mitcham cricket.

Memories such as these, highlighted by events like appearances of the

great Dr W G Grace, or the use of Mitcham Green in the early 1880s as

a practice ground by the first five or six visiting Australian elevens

(including one composed entirely of Aboriginees), and international

ladies’ matches in which during the late 1940s Mitcham’s own Hazel

Saunders excelled, ensure that the Green will long remain one of

Mitcham’s most cherished possessions. ‘Burn’ Bullock, one-time

honorary secretary of the Mitcham club, and licensee of the King’s

Head from 1941 until 1954, was at one time a professional cricketer

and played for Surrey for a number of years, mainly in the second XI.

‘Burn’ virtually carried the Mitcham club through the difficult war-time

period, and in the years that followed brought many famous clubs to

play on the Green. In a rare gesture the brewers after his death changed

the name of the old inn to the Burn Bullock in his memory, and the sign

now portrays Burn in his cricketing whites. Another ardent player and

supporter of Mitcham Cricket Club, Tom Ruff, a local shoe repairer

who died whilst mayor of Mitcham in 1961, is commemorated by a

simple stone memorial unveiled that May on a corner of his beloved

Green where in spring the crocuses bloom in profusion. Finally, mention

must be made of Frederick Cole. ‘Fred’ was the club’s president in the

1980s, and had been associated with Mitcham cricket for more than 50

years, both as a player and an official. His contribution to the club over

so long a period is certainly no less than that of others who, quite rightly,

are remembered from the early years of the village and its sport.

Notwithstanding its very long history (or perhaps because of it) the

Mitcham Cricket Club remains one of the strongest in the county and,

indeed, in the south of England.

THE CRICKET GREEN

The Village Playground

Cricket may have dominated the games played on the Green, but for

centuries the Green also served as the focal point of village recreation

and celebrations. It would be speculative to suggest that here were the

village archery butts, required as training grounds for bowmen by

successive English kings, not the least of whom was Richard II, son of

the Black Prince, whose emblem of the white hart can still be found in

one of the inns overlooking the cricket pitch. Equally fanciful would be

the thought that here, perhaps when progressing to her favourite palace

at Nonsuch, Elizabeth I paused to watch villagers dance in her honour,

and received their loyal addresses. Certainly during the national rejoicing

that accompanied Victoria’s Golden and Diamond Jubilees, and the

coronations of Edward VII and George V, the village was en fête. Old

photographs show buildings bedecked with flags and bunting, and the

Green itself swarming with people watching and taking part in the sports

which were de rigueur on such occasions. A first-hand account has

come down to us of the festivities marking the marriage of Albert

Edward, Prince of Wales, to Alexandra of Denmark in 1863, and is

worth recounting in full:

“That was a red letter day for Mitchamers, when England’s most popular

Prince was married to one of the kindliest ladies who ever shared the

throne. Public dinners were given in most parishes throughout the

kingdom; at Mitcham it was given in the National Schools, and old

Jacky Winders, the butcher, with ruddy face and ample waist, carved

the enormous joints of beef supplied for the occasion. Everyone who

cared was invited to take part in the feast, and well they were regaled

with the roast beef of Old England, plum pudding and a draught of

good beer, not like the chemical preparation retailed under that heading

today. That was before the great temperance movement in the late

‘sixties, and it was not considered a sin to partake, in moderation of

course, of the national beverage. After the dinner there were great

sports for all and sundry on the village green. Running and walking

contests were not confined to youths of the sterner sex, but matrons

over forty and rosy-cheeked broad-bosomed lasses were invited to

take part in races at distances to suit their age; not only did the long

jump, standing jump and high jump entice many competitors, but the

pole jump, at which the cross bar at 13 feet was cleared, and the hop,

THE CRICKET GREEN

Costumed participants in an Elizabethan Pageant

on the Lower Green in 1911

skip and jump, seldom heard of today, gave opportunities for display

of great vigour. The latter may seem too childish for these days of

professional sport, but to clear 40 feet at the combined effort of hop,

skip and jump might heavily tax the agility of the professional footballer.

There were no professionals in any branch of sport in those days, and

no gate money.

“After ‘Kiss in the Ring’ and similar games in the evening the sport of

the day was concluded by an enormous bonfire on the Common, the

reflection of which might be seen for many miles around. The position

of the fire was about half way across the part of the Common now

occupied by the railway, which was not cut until the following year”.21

Such was the enthusiasm with which the villagers threw themselves

into local celebrations that the Green seems rarely to have been left in

peace for long. Even an event such as the “christening” of a new fire

engine was regarded as a heaven-sent opportunity for rejoicing.

THE CRICKET GREEN

Nothwithstanding the cold of a January day in 1884 when Miss

Czarnikow of Mitcham Court broke a bottle of champagne over

“Caesar”, the parish’s newly-acquired horse-drawn steam engine,

hundreds turned out to cheer.21

Each year had its sequence of events, starting with Easter Monday,

when there was plenty of simple enjoyment and sports. Greasy pole

climbing, hurdle jumping, walking and running matches and sack races

attracted the athletic, whilst “bobbing” for treacled rolls, dipping for

oranges, and grinning through the horse collar caused plenty of laughter.

As always, donkey rides were popular amongst the old and young. On

Whit Mondays the benefit societies of the parish, rejoicing in such names

as the Amicable Society, the United Friends, and the Saturday Nights

Club22 met for their annual dinners, preceded by a parade round the

Green with bands and banners – a sight guaranteed to bring out the

crowds. The parade over, members of the societies and their families

would sit down to their dinners in the various inns and halls, and after

the inevitable speeches and toasts, dancing lasted well into the night.

The annual Epsom race week created another eagerly awaited diversion.

On Derby Day in particular, when the Green and the main road right

through Mitcham was thronged with people, schools were shut, since it

was impossible to induce sufficient children to attend. Until the latter

half of the 19th century there was no way of reaching the Downs other

than by road. As late as 1865 there were tollgates on the turnpike road

from London to Sutton – one at Figges Marsh and the other at Rose Hill

– and the press of traffic in the morning and again in the evening caused

jams which lasted for hours, everything moving at a walking pace. At

this time Royalty went by road like everyone else, and for years it was

the custom of the future Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, to stop

briefly for refreshment at the King’s Head whilst the horses were changed.

The cavalcade included scores of four-in-hands, and every conceivable

variety of vehicle from coaches and landaus to broughams and gigs and

the humble donkey cart. Always thrilling were the private carriages

bearing coats of arms of the nobility on their doors, and driven by liveried

servants resplendent in gold braid and buttons. Outshining all were the

beautiful dresses and hats worn by the society ladies, accompanied by

immaculately dressed gentlemen.

THE CRICKET GREEN

The toy shops along the way used to do a roaring trade on these days,

the “quality” delighting in buying trinkets and small toys which they

threw to the children who lined the roads to see them go by. They also

tossed out handfuls of coppers, for which the village urchins would

noisily scramble. “Everyone seemed to have plenty of money to throw

away at this time, both rich and poor”, remembered one old Mitchamer

in 1912 “for there was money and toys in one continual stream being

thrown on all sides as they passed along the road. Nothing of that sort

now”, he observed ruefully.21

Apart from cricket, Mitcham Green is probably associated most in the

minds of the present generation with the annual crowning of the May

Queen, and the procession from the Roman Catholic church in Cranmer

Road to celebrate the feast of SS Peter and Paul on the 29th June.

The May ceremony, formalised in a pretty Saturday afternoon’s

diversion, now attracts mainly the participating children and their

admiring parents. Although there is mention of a maypole to be seen

on the Upper Green in the late 18th century, the earliest record of the

crowning of the May Queen in Mitcham is a faded photograph dating

to about 1900 in the Merton Local Studies Centre collection. This

portrays a decorously-posed group of young ladies, a little older than

the children who take part today. None of the surviving personal

reminiscences of Mitcham life in the mid-19th century mention the

May Queen or the maypole, and both are relatively recent revivals of

old traditions. It was John Ruskin who sems to have been responsible

for awakening interest in May Day celebrations in the 1870s and 1880s,

and the Catholic procession is an even later addition to the Mitcham

calendar, but well-established by the 1930s.

The “Dig for Victory” campaign of the Second World War saw the

southern part of the Cricket Green pressed into temporary service as

vegetable gardens, which remained in cultivation until the early 1950s.

The land was then cleared and returned to grass, one ash tree (an

allotment holder’s bean pole that had taken root) being left as a memento.

The ugly chestnut paling which also dated from the war-time period

was removed in the 1970s, to be replaced by a slightly more elaborate

version of the old oak post and iron bar barrier which surrounded the

Green before the war. Sadly the new fence, with its double rails and

THE CRICKET GREEN

lower part enclosed with chain link, no longer provided budding gymnasts

with a horizontal bar over which to perform somersaults. New iron

railings, thought to be more aesthetically pleasing and therefore better

suited to the Conservation Area, were provided in the early 1990s.

Also gone are the hollow remains of several fine old elms which were

a delight to small boys and girls. Until the late 1960s and early 1970s

half a dozen or so survivors remained outside Mitcham Court, opposite

Barclays Bank, and across the road from the Tate Almshouses. To the

regret of many, Dutch elm disease and the need to widen the road by

the traffic lights finally necessitated their removal.

Today the Cricket Green forms part of the Cricket Green Conservation

Area, declared by the London Borough of Merton in 1969 and extending

from the Three Kings Piece as far as the parish church in Church

Road. A rare survival of a village green in the London suburbs, it is still

surrounded by much that is evocative of old Mitcham, and although at

peak hours the presence of heavy traffic is disturbing, at other times,

typically on a summer’s evening with a game of cricket in progress, one

can imagine that time has stood still.

The White House, Chestnut Cottage and Victorian villas

overlooking the Cricket Green. 1972

Chapter 2

THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL

During the reign of King Edward the Confessor, Aelmer, a Saxon thegn,

was in possession of an estate in Wallington hundred which, although

its location was not made explicit in Domesday Book, can be argued

with a degree of certainty to have been in central Mitcham. The case

rests mainly on what is known of the subsequent history of the ‘tithing’

of Mitcham, which came to form part of the Surrey estate of the de

Redvers family, earls of Devon and Wight from the early 12th century,1

and as the manor of Vauxhall was granted to the prior and convent of

Christ Church Canterbury in 1362.

At the time of the Domesday survey Aelmer’s former holding comprised

two hides and one virgate, or about 270 acres (108 ha), of which nine

acres were “meadow”. The latter were probably water meadows and,

if we are correct in locating the estate in Mitcham, would most likely

have been close to the Wandle. Three plough teams, a fair number for

a holding of this size, worked the arable land, and the 13 households

living on the estate can be estimated to have comprised in all between

60 and 70 persons.2 Aelmer seems to have been a man of considerable

wealth and standing, for he is recorded as holding no fewer than 12

separate estates elsewhere in Surrey. He also owned two watermills,

and possessed a half interest in three others. The name Aelmer was

by no means uncommon, however, and it must be admitted that the

Domesday entries may relate to more than one individual. By 1086,

when the survey was conducted, England was a conquered nation, and

the former Saxon landowners had to a large extent been dispossessed.

Aelmer’s widely scattered properties were confiscated and re-distributed

amongst several Norman nobles, including the Count of Mortain, one

of the Conqueror’s half-brothers. Mortain’s principal estate in Surrey

was the manor of South Lambeth, previously in the hands of the canons

of Waltham Abbey, and when he died his lands, which included a

substantial part of central Mitcham held as a tithing of the Lambeth

manor, were inherited by his son.3

Amongst the Anglo-Norman knights who allied themselves to Henry I

in the struggle for power with his brother, Duke Robert of Normandy,

was Richard de Redvers. Until his death in 1107 de Redvers remained

THE CRICKET GREEN

one of Henry’s staunchest supporters, and his loyalty was rewarded with

the grant of lands in Devon and the Isle of Wight. Mortain, on the other

hand, suffered the penalty for supporting the Norman faction and,

following the defeat of Robert at the battle of Tenchbrai in 1106, forfeited

his property in Mitcham which, together with the manor of South Lambeth,

passed into the hands of de Redvers. Tenure was subsequently inherited

by Richard’s son Baldwin, the first earl of Devon, and a century later,

under King John, the estate was held by William de Redvers, who died in

1216.4

Following the death, also in 1216, of Baldwin de Redvers the 6th earl, his

widow Margaret married Falkes (or Fawkes) de Breauté of Fawkes Hall,

or Vauxhall.4 De Breauté, energetic and ruthless, was one of King John’s

executors and a loyal member of the Council responsible for the affairs of

state during the minority of Henry III. The de Redvers’ manor of South

Lambeth, including the tithing at Mitcham, passed into his hands on his

marriage to Margaret, and it is from him that the manor of Vauxhall

derived its name. When Falkes died in 1226 his houses in Lambeth, and

the rest of his property associated with the manor, were granted by Henry

III to de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, to hold until the son and heir of Baldwin

de Redvers should come of age.

Baldwin, the 7th earl of Devon and Wight, married Amicia de Clare,

daughter of Gilbert, 5th earl of Gloucester and Hertford, during the royal

Christmas celebrations at Winchester in 1240. The couple were betrothed

as children in 1223, and the match had the approval of Henry III, before

whom the marriage took place amidst great celebration.5

Within five years Baldwin was dead, “cut down in the flower of his youth”,

leaving Amicia a widow at the age of 25, with three small children one of

whom, Baldwin, became the eighth earl of Devon. In 1259 a “Bartholomew

de Lisle”, presumably acting during the eighth earl’s minority, had granted

the advowson of the parish church of Mitcham to the prior and convent of

St Mary at Southwark.6 (The grant is likely to have been in confirmation

of earlier grants by the family, for it is clear the church had actually been

in the possession of the priory for a hundred years or more.)7 The

formalities were completed and the grant confirmed the following year

by Baldwin, acting through Adam de Stratton his clerk.8

THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL

In 1260 Baldwin, by this time one of the group of young bachelors who

were intimates of Prince Edward (later to become Edward I), had been

moved to give further expression of his favour to the Church by granting

to Eustace, the prior of Merton, a moiety, or half share, in a watermill.9

Baldwin was now in possession of the family’s Mitcham estate, and

from future references to the mill as “Pippes” or Phipps mill it is clear

that it stood on the bank of the Wandle at Phipps Bridge. With this

knowledge, and also the history of other properties in Mitcham held in

later years of the manor of Vauxhall, it is possible to be fairly confident

that the estate was that in Mortain’s tenure in 1086, and that it extended

from the Wandle eastwards across central Mitcham as far as

Commonside West.

Baldwin was poisoned in a palace plot in 1262,10 and the inquisition

post mortem confirmed that amongst his property was an estate in

Mitcham, held as “an appurtenance” of his manor of South Lambeth.11

A copy extract from the report of the enquiry gives the rents of free

tenants in Mitcham due to “Lord Baldwin de Insula in Surrey …… in

1263”.12 These rentals were “assized”, ie the amounts were verified

by the court, and found to total £3 8 5½d. The tenants’ names and the

size of their holdings were recorded, and included “The Prior of Merton

(who) renders 20s for the mill which is called Pypesmoln” and “Hugh

at Church” (presumably the parish priest) who held a virgate of land.

The extent of the de Redvers’ lands in Mitcham is of course difficult to

determine precisely, but if we take a virgate to represent very roughly

15 acres (6 ha), the average for Surrey, we arrive at an estate of roughly

two and a half hides, or some 300 acres (120 ha). This is very close to

the size of Aelmer’s holding in Wallington hundred at the time of the

Conquest, and gives further support to the belief that the de Redvers’

estate embraced much, if not all, of the land held by Mortain in Mitcham

in 1086.

Following Baldwin’s murder the manor of South Lambeth or Vauxhall

was held in dower by his widow Margaret. She remarried, taking Robert

de Aguilon as her second husband, and was still in possession in 12789,

when they had to answer a writ of quo warranto, requiring them to

prove their right to tenure.3 Margaret and Robert retained lordship of

the manor, holding it “of the inheritance” of Baldwin’s elder sister, the

THE CRICKET GREEN

Lady Isabella de Fortibus, but after Margaret’s death tenure of the

family’s estates passed to Isabella, a lady much given, either by

inclination or force of circumstance, to litigation.13 The widow of the

count of Albermarle, she was one of the wealthiest women of her time,

and was involved in one of the worst judicial scandals of the 13th century,

in which over 700 officials, high and low, were implicated. Lady Isabella

died in 1293, immediately after being persuaded (some would say

tricked), into selling her hereditary lordship of the Isle of Wight and her

manors to Edward I for £4,000.14

The whole of the Mitcham estate thus passed into the hands of the

Crown, and we find reference in 1301 to “Pippes” mill being held in

capite, ie directly of the king, the prior of Merton paying homage as a

tenant-in-chief to Sir Ralph de Marton on behalf of Edward I.15 In

1315 Hugh de Courtney petitioned for the property of the late Isabella

de Fortibus, countess of Albermarle and Devon, but the outcome is not

known.17 An enquiry into the extent of the manor of Vauxhall in 1318

further confirmed that it included the watermill known as Phipps Mill

at Mitcham, still held as a manorial tenant by the prior of Merton.18

In September 1337 lordship of the manor of Vauxhall, together with

Kennington, passed into the hands of Edward Duke of Cornwall, the

“Black Prince”. Vauxhall was amongst various properties Edward

granted to the prior and convent of Canterbury in 136219 to guarantee

the expense of maintaining, in the crypt of the cathedral, a chantry

chapel which he founded the following year as the price of papal

dispensation to marry his beautiful cousin, the widowed Joan of Kent.

Edward, one of the most charismatic figures of the Middle Ages, was

born in 1330, the eldest son of Edward III. At the age of 16 he had been

left in command at Crecy when his father retired from the field, and

deployed the English long-bowmen with such skill and effect that the

French were completely routed. Understandably idolised by his men

and the country, he came to epitomise the popular ideals of chivalry and

bravery. Edward died in 1376, and although in his will he directed that

he should be buried in the lady chapel in the undercroft at Canterbury,

popular opinion demanded a more honourable place for the nation’s

hero, and he was accordingly interred close to Becket’s tomb on the

south side of the chancel of the cathedral.20

THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL

At an inquisition post mortem held following the death in 1392 of Sir

John Burghersh, lord of the manor of Ravensbury, it was confirmed that

he had been in possession of the copyhold tenancy of “a parcel of land

called Allmannesland” which he held of the prior of Christ Church,

Canterbury, lord of the manor of “Faukeshall”, paying six shillings a year

as a quit rent in respect of all feudal services due.21 During the priorate

of Thomas Chillendon (1391-1411) leaseholds came to be granted on

many of the Canterbury estates, and in 1424 “Allmannesland” was held

by John Arundel of Bideford, who had acquired tenure by right of his

late wife, Margaret née Burghersh.22 Half a century later it was held

by Sir Richard Illingworth, chief baron of the exchequer to Edward IV,

who died in 1476.23 Today the land and the house which has stood on it

since the latter half of the 18th century are known as Park Place, and

the property was still copyhold of the manor of Vauxhall in the 1820s.

The name “Allmannesland” (in some later documents it is shortened to

“Almonds”) clearly enshrined the folk memory that it had once been

common land, and today it lies between the Cricket Green and Three

Kings Piece, both of which survive as public open spaces. In 1236 the

Statute of Merton had declared legal the taking of common land by the

lord of a manor provided sufficient pasturage for the commoners’ cattle

remained on the parish waste, but we have nothing to indicate whether

the enclosure of Allmannesland occurred before or after the manor came

into the hands of the prior and convent of Canterbury.24

In 1428 the prior of Christ Church was confirmed to be holding two

hides (of which one hide, or about 120 acres (48 ha), carried the annual

obligation of paying one-fifth of a knight’s fee) in Mitcham, described as

having once been in the king’s hands and subsequently of Edward, the

former Prince of Wales.25 The estate, which was to prove a most

profitable one in future years, together with the lordship of the manor of

Vauxhall, passed into the possession of Canterbury Cathedral following

the Dissolution26 and, apart from a brief period during the Commonwealth,

remained under the control of the dean and chapter until the 19th century,

when it was appropriated by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.

Whereas there appears to be no surviving map or terrier of the tithing of

Mitcham, there are numerous clues to the extent of the manor of

THE CRICKET GREEN

Vauxhall’s jurisdiction. Phipps Mill, which we have already mentioned,

lay at the western extremity of the estate, and Allmannesland to the

east. Hall Place, off Lower Green West, one of the larger medieval

houses known in Mitcham and believed to have been the seat of the

Illingworth family during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, is said

to have been held of the manor by another Sir Richard Illingworth in

1512, and passed to his son William.27 Hall Place had both a dovecote

(an asset customarily restricted to the demesne farm of a manor) and an

open hall. Both features imply that the house had a status above that of

the rest of the dwellings in the vicinity, and that it was at one time the

residence of someone of at least local importance.

In the 16th century, land to the south of the Cricket Green, forming the

northern part of the grounds of the “mansion house” of Thomas Pyner,28

seems to have been held of the manor. By the early 17th century the

former Pyner estate was subdivided for redevelopment, providing the

site for what in later years was known as the Manor House, Lower

Mitcham. Although this property was mainly freehold, court rolls show

that a quit rent (for what one assumes was a portion of the grounds)

continued to be demanded of owners throughout the 18th century. From

rent rolls of the manor it can also be seen that the King’s Head29 and

the land overlooking the Cricket Green on which the Tate family’s house30

stood in the 18th century were likewise held of the dean and chapter of

Canterbury.

References to the manor pound occur several times in the court rolls,

one of the earliest being from the Commonwealth period, when Mitcham

pound was reported to be “much decayed” – a hint that it was little

used, and certainly neglected, in the mid-17th century. The occasion

was a survey of the manor of Vauxhall conducted in 1649 pursuant to

one of Cromwell’s early Acts, by which lands held by the dean and

chapter of Canterbury were sequestrated in October of that year. (The

estates were restored to the archbishop after the Restoration.)31

The need for a secure pound which could be used when the occasion

demanded seems to have become an issue of some importance towards

the end of the 18th century. The annual Mitcham fair attracted large

numbers of gypsies and other travellers who, after the fashion of their

THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL

kind, no doubt left their horses and other stock to graze on the Common

and the various greens of Mitcham with scant regard for the rights of

commoners and copyholders of the manors. Whether or not the renewed

interest in the condition of the pound had any connection with efforts

being made in the early 1770s to suppress the fair it is difficult to say,

but the coincidence of dates suggests the two might have been linked.32

At the court leet held on November 7th 1775, it was reported by the

four officers from the tithing of Mitcham that the pound belonging to

the manor of Vauxhall was out of repair.33 Although the court rolls

record the decision that the pound ought to be repaired by the lord of

the manor, nothing seems to have been done, for two years later the

headborough, William Oxtoby, reported to the court that the pound was

still “greatly out of repair”. In 1780 the officers again presented to the

court that the common pound for the “liberty of Mitcham” continued to

be “so out of repair that no estrays or trespassing cattle can be secured

therein to the great loss and damage to the Lords’ Tenants of the said

Manor, and that the pound ought to be repaired by the Lords of the

manor”. A year later, by now obviously exasperated at the lack of

response to their previous presentments, the jurors threatened “a suit or

prosecution against the lords for their neglect” if they failed to put the

pound in “good and sufficient repair” by January 1st 1782. With their

bluff called (if, indeed, it was a bluff,) and still with no apparent

satisfaction from the dean and chapter, it was minuted at the court leet

in November 1782 that “Whereas the parish of Mitcham has for the

last five years presented the said pound of the said parish as being

useless and have received no redress”, the frustrated jury “do hereby

firmly make this their presentment that if the pound is not repaired by

the Lords of the Manor within one year the said jury will not keep the

court”.34 The court was reconvened in November 1783, but no Mitcham

business was conducted, apart from imposing a fine on the constable,

Thomas Chesterman, £5 for non-attendance. The fine had little effect,

for both constable and the headborough were fined for non-attendance

at the meeting in 1784. Oliver Baron, a local magistrate who had been

a prominent member of the justices’ committee appointed to suppress

the fair, died in 1786, and thereafter the officers and copyholders seem

to have lost interest not only in resolving their dispute with Vauxhall,

THE CRICKET GREEN

but also in the condition of the pound, and in 1787 it was reported to

have “totally fallen down”.35

After a lapse of nearly 20 years, during which nothing much seems to

have transpired, a new name, that of William Sprules, appears as pound

keeper in the court leet roll for 1801. This may be of some significance,

for certain landowners were beginning to show interest in the enclosure

of Mitcham Common, and for a while the vestry was to be much

concerned with the proper control of common grazing and the protection

of the rights of pasturage which had been enjoyed for generations by

the copyholders of the several manors of Mitcham. This was, of course,

during the Napoleonic wars, when there was a heightened awareness

of the increased output (and profit) which could be gained from marginal

land by recourse to modern husbandry. Several of the parishes adjoining

Mitcham were to lose their commons to enclosure at this time. In the

event, neither Mitcham Common nor any of the Mitcham greens were

enclosed, and remained “waste of the parish”.

Until the 18th century Vauxhall pound had been located off Lower Green

West, opposite the present fire station, but it was then moved to a site

on the Green itself, where it is shown on the tithe map of 1847. “Old

Billy Sprules”, who died in 1848, was still remembered as the pound

keeper by an elderly witness giving evidence in the case of the

Ecclesiastical Commissioners v Bridger and others in 1890.36 Within

his memory, he said, cattle straying from the Common had been placed

in the Vauxhall pound – proof that it played a part in the management of

the manorial waste at least until the middle of the 19th century. After

Sprules’ retirement, Newland, the landlord of the Cricketers, is said to

have acted as pound keeper, and had charge of the key.37 The land

occupied by the inn today must itself once have been enclosed from

the Green with, one assumes, the consent of the dean and chapter, but

precisely when this happened is not known.

The Lower Green and several of the houses overlooking it, including

No 7 Cricket Green (the White House), certainly remained within the

jurisdiction of the manor during the 19th century. Emma Bartley, who

lived at No7, recalled in her reminiscences of old Mitcham38 that changes

of copyhold tenure were still being formalised in the mid-19th century

THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL

by observance of the age-old ritual of “grant of livery of seisin”, with

the new owner, on admission to the tenancy of the manor, being required

to swear an oath of fealty to the lord of the manor in the person of his

steward.

Perhaps reflecting rising land values, manorial administration seems to

have become far more vigilant in the 18th century, and the formal consent

of the dean and chapter of Canterbury was deemed necessary by the

parish officers in 1765, when the Mitcham vestry wished to enclose a

plot on Lower Green West 12 feet by 20 feet for the erection of a watch-

house or lock-up.39 “Leave and license” was granted at “the small

acknowledgement of 1d per annum” on the condition that the Vestry

should be responsible for keeping the building in good repair. It is

understood their successors, the Urban District Council of Mitcham,

still considered it prudent, if not strictly necessary, to seek the

concurrence of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners when the erection of a

new fire station on Lower Green West was under discussion in the early

1920s.

In the case of the lock-up, which it was considered would be a “publick

Utility”, it had been the unanimous decision of the “parish in Vestry

assembled” that enclosure of a small part of the Green for the purpose

could be justified. There was no such unanimity in 1788 however,

when William Pollard, a newcomer to the parish who was the owner of

Park Place and a copyholder of Vauxhall, objected to the proposed

enclosure of part of Lower Green West to provide a site for a Sunday

School building. Plans had to be changed, and the school was erected

on an alternative site donated by the owner of Hall Place.40

Early in the 19th century, when the enclosure movement was at its height,

there was a real danger that a substantial part of the Green might be

enclosed. John Middleton, who had been commissioned by the dean

and chapter of Canterbury to conduct a survey of the waste lands lying

within the manor of Vauxhall, reported of “Mitcham Green” in 1806:

“Nearly one third of this is rough ground; to the enclosure of which

no person would object.

“The other part, of 8 or 10 acres, is a fine turf, in the middle of the

village, on which there is much Cricket playing. This Green is

THE CRICKET GREEN

surrounded by mean houses and Cottages, many of which are holden

of the manor of Fauxhall. What proportion of the inhabitants would

consent to a division of it, I have no means of Knowing, but this

Green is a good sheep pasture, and is the best feature of the village.

A few acres of nice green turf, adjoining the turnpike road, and in the

centre of a village, seems to contribute its just proportion to the benefit

of society.”41

Middleton concluded, after advising the dean and chapter of his valuation

of the land and its mineral rights if it were to be enclosed, that experience

had shown that where commons or greens were overlooked by persons

from London, living in “Genteel houses”

” … to obtain an act of Parliament without opposition cannot be

expected. It would chiefly be from persons who have not any right of

common joined by three or four who have …”

He invited the dean and chapter to consider whether they wished to

incur the expense of soliciting the tenants of the manor for their consents,

and then the charges for presenting a Bill, in the

” … small uncertainty as to whether the acts may be obtained or not,

for the value of their interest in case they should succeed.”

In a letter dated November 27th, Middleton advised the dean and chapter

that whereas enclosure of commons and wastes was of such obvious

benefit to the nation that it could be taken for granted “that the Legislature

will afford it every facility”, opposition could not be repressed and was

well known to involve the parties concerned in considerable expense for

perhaps little gain. As an alternative, he put forward the following

suggestion:

“Various persons have made many encroachments within the last eight

or ten years, and others have been enclosed for a longer time, these

persons may be induced to accept such grants” (of land, on payment

of a sum of money to the lords of the manor) “in preference to being

ejected by law. These several grants might be managed in such a

manner as to create a disposition in other tenants and inhabitants of

the manor to solicit for similar indulgences. Particularly the tenants

who compose the Homage Jury may be invited to negotiate with the

steward of the manor for such slips of waste as adjoin, or be

conveniently for their respectively tenements. I think this would

THE MANOR OF VAUXHALL

induce them to solicit for grants to be made to themselves on paying

for them. It would also increase the habit they are now in of giving

their consent to other grants, being made to strangers. By a union of

making grants in the first instance, and blinking at encroachments

till the parties can be brought into Court to accept a grant of them,

something considerable may be done in the short time; this system

seems to be calculated to continue for many years, or until all the

waste or Common land belonging to the Manor become enclosed.”

This course of action, devious as it might have been, seems to have

found some favour with the dean and chapter. Middleton’s advice would

certainly appear to have been followed in the case of a group of adjacent

properties at the northern corner of the Green, where the tithe map of

1847 shows very clearly that the land on which they stood must once

have been part of the Lower Green. In about 180742 Edward Tanner

Worsfold, the owner of Hall Place, a copyholder of the manor and a

member of the court leet from 1788 until 1804, acquired from a Mr

Spencer a plot of land at the corner of Lower Green and the turnpike

road leading to London which, for a number of years, had been occupied

by three very small cottages. These were soon demolished, and in about

1808, on the best part of the cleared plot, with a southerly aspect

overlooking the Cricket Green, he built Elm Lodge, an attractive villa

in the Regency style. Whitford Lodge and Whitford Cottage, which

stood on the remainder of the land to the rear until bombed during World

War II, were of later date, and had probably been erected around the

middle of the 19th century. All three remained copyhold of the manor

of Vauxhall until 1925, when they were enfranchised on application

being made to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.43

Management of the Lower Green, but not the mineral rights, passed

into the hands of the Board of Conservators elected after the enactment

of the Metropolitan Commons (Mitcham) Supplemental Act 1891. This

remained the situation until April 1924 when, following the passing of

the Mitcham Urban District Act of 1923, the Mitcham greens were

vested in the new local authority. Like the Urban District Council it

superseded, the Borough Council of Mitcham, which received its charter

in September 1934, showed little compunction in building on the Green

when councillors deemed the development to be in the public interest.

THE CRICKET GREEN

The Vestry Hall, erected in 1887 on the site of the village lock-up,

already occupied a considerably larger parcel of land than that originally

sanctioned in the 18th century, and was doubled in size in 1930 by the

building of a large extension to the rear. The need to provide

accommodation for the growing number of staff employed at the Town

Hall led to the construction of an ugly outbuilding on yet another portion

of Lower Green West shortly before World War II, and this, although

intended to be only a temporary structure, still stands today, occupied

by the Wandle Industrial Museum.

In recent years the desire to improve the movement of road traffic has

resulted in road-widening on several occasions, again at the expense of

the Green. Occasionally pleas are heard for a site to be made available

on the Green for a new cricket pavilion but, obvious as the advantages

would be for the cricketers, it is to be hoped that such an encroachment

on what remains of the Green will be always be rejected in the wider

interests of the Conservation Area.

The Vestry Hall and the Cricket Green seen from outside the King’s Head

(Copy of postcard c1905)

Chapter 3

THE BURN BULLOCK

(FORMERLY THE KING’S HEAD)

The Burn Bullock or, to give the inn its earlier name, the King’s Head,

occupies a commanding position at the corner of the Cricket Green and

the main London Road. It is certainly the most impressive and, so far

as one can tell, probably the oldest of the various inns and public houses

that abound in Mitcham,1 and 200 hundred years have now elapsed

since it was described in a guide to buildings and other items of interest

on the road to Brighton as a “large, good-looking inn”.2 Happily, although

the name has changed, the building has altered little in external

appearance since that time. The compiler of the guide was J. Edwards,

and his modern counterpart would have little cause to disagree with his

assessment, for the inn has withstood the passage of time remarkably

well. “Modernisation”, where it has taken place at all, has been discreet

and for the most part gradual, serving to reflect the passing years through

subtle changes which have actually added to, rather than detracted from,

the historical interest of the premises.

The earliest evidence we have for the inn’s age is in its architecture – the

rear of the building showing every indication of being of late 16th or

early 17th century in date. Here heavy structural timbering survives,

and is particularly in evidence on the ground floor, where it adds to the

attractions of the lounge bar and dining room. Much of the exposed

woodwork shows signs of having been re-used, a reminder that by Tudor

times good structural timber was scarce and therefore expensive in this

part of Surrey. Externally the rear wing, with its gablets, its tile-hung

upper storey, oriel window and massive chimneys, again speaks more

of the late Elizabethan period than of the Jacobean. So much for the

superficial features; a more detailed and expert examination, particularly

of the roof timbers, would undoubtedly prove revealing.

The first documentary evidence for the building is in an indirect reference

to the “farm house of Sir Julius Cesar”(sic). This is contained in a 20year

lease dated 20 March 1604/5 involving a neighbouring property to

the south, granted by George Smyth of Mitcham to a John Bowssar,

citizen and vintner of London.3 Sir Julius Caesar, who had been knighted

THE CRICKET GREEN

The King’s Head and gardens, the National School and the Almshouses, shown

in a plan produced for an auction in 1888. (Courtesy of Surrey History Centre)

THE BURN BULLOCK (FORMERLY THE KING’S HEAD)

by James I two years previously, was the owner of a mansion to the

south of the Cricket Green, standing in grounds which are now covered

by the houses in Mitcham Park and Baron Grove. One of the leading

lawyers of his day, he had been host to Queen Elizabeth on three

separate occasions, and was to become Chancellor of the Exchequer

in 1606, and Master of the Rolls in 1614.4

Another important document dealing with the history of the King’s Head,

for many years hanging in a glazed frame in the dining room, seems

most unfortunately to have been removed during a change in management

in the 1970s.5 Its present whereabouts are unknown, but the writer

recalls that it was a lease or conveyance of around 1620 granted by Sir

Henry Savile of Methley in Yorkshire, who was Sir Julius Caesar’s

son-in-law. The actual transaction possibly took place in 1623, when

Sir Henry and his wife sold other land in Lower Mitcham which she

had inherited. Precisely what property the document related to cannot

be confirmed until the deed is traced, but Lily Bullock, the licensee in

the 1960s, believed it to be an early lease of the King’s Head. One can

only hope that such a valuable piece of evidence for the early years of

the inn has not been lost forever, and that it will re-emerge in the fullness