Memoir of Priscilla Pitt, by John Marsh Pitt 1899

Local History Notes 33: by John Marsh Pitt 1899

Local History Notes 33: by John Marsh Pitt 1899

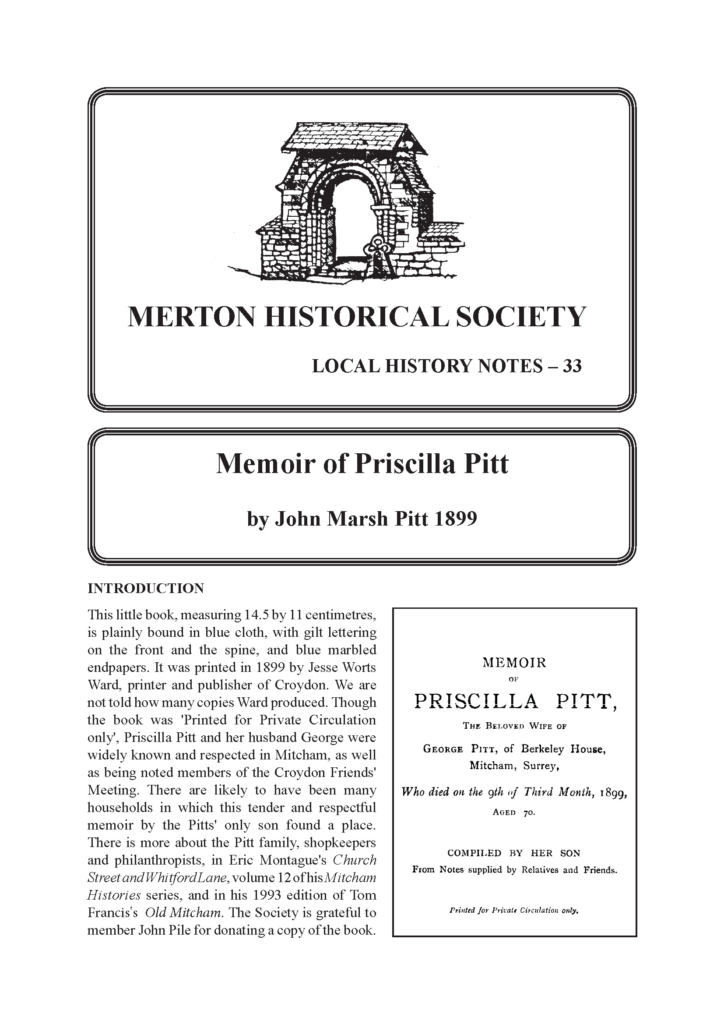

John Marsh Pitt produced this Memoir to his mother shortly after her death in 1899, and the Society is grateful to member John Pile for donating a copy of the book for reproduction. ‘This little book, measuring 14.5 by 11 centimetres, is plainly bound in blue cloth, with gilt lettering on the front and the spine, and blue marbled endpapers. It was printed in 1899 by Jesse Worts Ward, printer and publisher of Croydon. We are not told how many copies Ward produced. Though the book was ‘Printed for Private Circulation only’, Priscilla Pitt and her husband George were widely known and respected in Mitcham, as well as being noted members of the Croydon Friends’ Meeting. There are likely to have been many households in which this tender and respectful memoir by the Pitts’ only son found a place. There is more about the Pitt family, shopkeepers and philanthropists, in Eric Montague’s Church Street and Whitford Lane, volume 12 of his Mitcham Histories series, and in his 1993 edition of Tom Francis’s Old Mitcham.

From the Introduction to the Society’s edition

Click on the image on the right to download a free pdf of this publication.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

LOCAL HISTORY NOTES – 33

Memoir of Priscilla Pitt

by John Marsh Pitt 1899

LOCAL HISTORY NOTES – 33

Memoir of Priscilla Pitt

by John Marsh Pitt 1899

INTRODUCTION

This little book, measuring 14.5 by 11 centimetres,

is plainly bound in blue cloth, with gilt lettering

on the front and the spine, and blue marbled

endpapers. It was printed in 1899 by Jesse Worts

Ward, printer and publisher of Croydon. We are

not told how many copies Ward produced. Though

the book was ‘Printed for Private Circulation

only’, Priscilla Pitt and her husband George were

widely known and respected in Mitcham, as well

as being noted members of the Croydon Friends’

Meeting. There are likely to have been many

households in which this tender and respectful

memoir by the Pitts’ only son found a place.

There is more about the Pitt family, shopkeepers

and philanthropists, in Eric Montague’s Church

Street and WhitfordLane,volume 12 of his Mitcham

Histories series, and in his 1993 edition of Tom

Francis’s Old Mitcham. The Society is grateful to

member John Pile for donating a copy of the book.

PREFACE

The great respect shown by friends and neighbours at the decease of PRISCILLA PITT, makes

it seem desirable that a short memoir of her life should be prepared as a memento of her loving

character, and as an encouragement to those of us still living, for

“Lives of good men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.”*

As regards the photographs here reproduced, it is questionable if PRISCILLA PITT would herself

approve of their insertion, but we have felt that her objection would merely arise out of modesty.

Her countenance being unusually emotional and varied in expression, it was impossible to get

any one portrait to do her justice, hence we have selected four, each taken, without preparation,

in the garden.

Having but a humble opinion of herself she would always shrink from display.

This Memoir is not written to exalt the creature, for what she was, she was through the Grace of

God, who will equally work His good works in us if we will be obedient to His requirements.

Copy of Memorial Card

Poem printed on flyleaf – author not identified

“What monuments, splendid in

marble,

Are built where our conquerors

lie!

But what is the fate of such

women?

To do what is good and to die!

All honour to true wives and

mothers

Who bravely their crosses have

borne,

And hundreds and thousands are

victors,

But never have diadems worn.

And whether in cottage or

palace,

Obscure, or of royal renown,

Humanity, rectitude, duty

And love, are of woman the

* from A Psalm of Life by Longfellow. It should read ‘Lives

crown.”

of great men …’. Further verses are quoted on page 6.

MEMOIR

PRISCILLA MARSH was born at Peckham, the 24th of

Eleventh Month,* 1828, and, while an infant, was moved

to 32 (now No.50) Park Lane, Croydon, where her parents

resided for nearly half-a-century, adjoining the large

Friends’ School, and near the Friends’ Meeting House.

Her father, JOHN FINCH MARSH, who had been a linen

draper in Whitechapel for many years, retired on a small

income in 1828. He was an “acknowledged” Minister of

the Society of Friends, travelling in the ministry several

times in parts of England, three times through Ireland, and

once on the Continent. His voice was often heard at the

Croydon Meeting House, his ministry being simple and

affectionate. He was one of the old school of Friends,

wearing the stand-up collar, coat, drab breeches and

gaiters, and broad-brimmed hat. It might be said of him,

“An Israelite, indeed, in whom there was no guile.” His

strongest characteristic was love, which his face clearly

bespoke.

Her mother’s maiden name was HANNAH LUCAS, daughter of a London corn dealer. She had

a noble and stately form and bearing, and, like her husband, was for over 50 years a recorded

Minister in the Society. She wore the spotless garb of the early Quakers.

The subject of this Memoir had but one sister to outlive infancy – HANNAH MARSH, afterwards

HANNAH BOWDEN –several years her senior, who qualified for teaching, and wrote a number

of excellent poems, which were edited and published by PRISCILLA PITT after her sister’s

decease at the age of 36. The hearts of these two were very closely knit. HANNAH once told

a friend that PRISCILLA “had the most delicate perception and the most pure refined mind of

truly any person she had ever met.”

PRISCILLA PITT always treasured up a deeply affectionate regard, amounting to reverence,

for her parents and sister, and was devotedly attached to her numerous aunts, uncles, and near

friends. Everything which they had used or touched was looked upon as sacred; and many times

in after life did the tears come to her eyes as she recalled her happy days of childhood.

When about 19 years of age she was visited with a severe brain fever, and lingered on the

borderland of Eternity for weeks, it being thought impossible for her to recover. In this illness

she evidenced

the true unfaltering foundation of her simple trust and childlike confidence, in

which the dread of death was entirely removed.

On attaining her majority she displayed remarkable benevolence by providing substantial benefits

to the many poor amongst her neighbours, by whom at that early age she was greatly loved; but

she declined all celebration of the event in the form of personal enjoyment.

She received a good education at two schools, and with several of her schoolmates kept up

intimate correspondence till their deaths. She was trained in domestic duties and in sound

Quaker principles, wearing the “plain dress” like her parents, with whom she remained until

her marriage at 32 years of age.

* Note the Quaker way of styling the months and days

Priscilla Pitt 6.8.1894, aged 66

GEORGE PITT attended Friends’ Meetings for

the first time in 1853 at Croydon, frequently,

walking to and from Mitcham twice a day on

Sundays. Becoming convinced of Quaker

principles, he was admitted into membership

in 1857. An acquaintance with PRISCILLA

MARSH thus formed, resulted in his proposal

of marriage, but her parents doubting the

suitor’s ability to keep a wife discouraged

his overtures. Still, they loved each other,

and love laughs at difficulties, and finally in

Tenth Month, 1860, they married, and came to

reside at London House, Mitcham. Here they

carried on a third-class drapery and clothing

business with the smallest beginnings, not

clearing expenses for some months, but by great

industry and thrift they soon turned the corner

and succeeded beyond expectation, retiring in

nine years on a small capital in favour of their

assistants.

Five precious children were born here, but He who gave saw fit to take away, which loss,

though borne in resignation, was a most terrible wrench, and was the immediate reason of their

retirement from business.

They moved to Berkeley Cottage, living on an income which, though only moderate, yet was,

with their plain habits, enough. In after years they bought or built numbers of cottages, and in

this way were always kept in contact with the poorer classes.

After being two years without any children, they had, in 1871, a son born, their present and only

surviving child taking his grandfather’s name, “JOHN MARSH.” To rear this child became “the

prayer, the hope, and delight of his parents,” especially of his mother, whose gratitude knew no

bounds when he arrived at manhood.

JOHN FINCH MARSH died in 1873, at Croydon, aged 84, and GEORGE PITT’S father

having died six years previously, at Richmond, aged 63, the two widows were invited to join the

household at Mitcham, all moving into “Manor House,” next door, in 1876. Here HANNAH

MARSH died next year, aged 87, and the family moved into Berkeley House in 1880. This

house had just been vacated by WALTER FRY, grandson of the celebrated ELIZABETH FRY.

Here G. PITT’S mother, ELIZABETH PITT, died in 1881, aged 74.

The household having been thus reduced, GEORGE and PRISCILLA PITT, then being about

50 years of age, decided to travel in foreign countries. This they did at intervals, visiting all the

chief places of interest in Europe, Egypt, and Palestine. Also America (twice), Canada, India

(very largely), China, and Japan. In 1895 they went to Central Asia as far as Samarkand, over

the Caspian Sea and Desert of Kara Kum, also down into Persia, and home across the Caucassian

Mountains and Black Sea, visiting the Crimea.*

* George Pitt published a poem entitled AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A MITCHAM WORKING MAN, describing these

foreign travels. It is reproduced in E N Montague Mitcham Histories 12: Church Street and Whitford Lane

(MHS 2012) pp.121-125

At marriage 1860

The peculiarity of these extensive travels was the

extreme cheapness of their cost, being perhaps

not more than one-third of that ordinarily spent.

Such travelling was thrilling and delightful,

but, much as G. PITT enjoyed it, he could not,

owing to his deafness, have accomplished it

without his wife’s company and aid. He called

his wife his ear and mouthpiece, his French

and German linguist, and declared there was

not another woman in England like her, for she

never complained, did not mind roughing it,

and was always cheerful. They seemed to be

able to go anywhere and do anything, together.

PRISCILLA PITT was an unusually active

person, thinking nothing of walking about all

day. On her 70th birthday she took a skipping-

rope and showed her grand-children that she

could still enjoy that juvenile exercise. She

was an early riser, often being up at five or six

o’clock, and was generally the last to retire at

night. She was a great believer in fresh air,

and would open the windows whenever a chance presented itself, and until her last few years

enjoyed a cold bath most mornings. She had a great love of the country, and appreciated the

beauties of nature intensely – the flowers, the trees, and the song of the birds, and would often

regret that the beauties of the sky were so little appreciated.

In 1880, when at Manor House, PRISCILLA PITT started a Band of Hope, getting about 300

children to join. The meetings were held in the large parlour, and were very lively. Many of the

members still remain true to their pledge. Two of them, whom she afterwards visited in America,

had their framed Pledge Cards still hanging up. This juvenile attempt was the nucleus of the

larger Adult Society formed in 1893 – “The Berkeley Teetotal Society” – in which she always

took an active part in helping by writing and speaking. She was a thoroughgoing abstainer,

saying that she would not even give the Queen a glass of wine if she called upon her. She had

no sympathy with those who violated the meaning of “Temperance” by making it stand for

halfway measures, a dilly-dallying with evil.

No, if a thing was unnecessary and injurious she would entirely abstain, and make no occasion

of stumbling to her weaker brethren. She first signed the pledge as a child at Croydon when the

movement began. Often did she assure people that sooner than see her only son take to drinking

she would rather follow him to the grave.

In 1895 PRISCILLA PITT was elected a District Councillor and Guardian of the Poor for several

parishes united. She attended the many meetings regularly, and zealously performed her duties.

Her work was much appreciated by her colleagues, and she was especially beloved by the poor,

whose cause she championed. Even after her term of 21 years expired she still served on the

Boarding-out Committee till the day of her death.

In 1896 it was almost arranged to visit the sites of Babylon and Nineveh and make a tour through

Tunis. The ship had even been selected to start by, when she took a severe chill and her breathing

became short and laboured so that the idea had to be abandoned.

Priscilla Pitt 6.8.1898, aged 70,

and her grandson Ernest

This bronchial affection became chronic, and was more or less obvious for the last two years,

and in the Winter of 1898 another cold obliged her to give up her usual duties and keep indoors.

This was a great trial to one naturally so active. Except when very unwell, or away from home,

she would never give up the rent collecting, because she liked to talk to and sympathise with the

poor tenants. Often did she take them comforts or make arrangements for their welfare. They

loved her in return, and a large number of them followed her to her last resting place.

Even though chiefly confined to the house for the last few months, she went out occasionally

where duty called.

The last two meetings she attended were the Parish Meeting in support of the International

Crusade of Peace, and a week before her death, a Committee of the Society for the Prevention

of Cruelty to Children, in both of which subjects she took a lively interest.

The following day she became suddenly worse and the doctor was called in, who gave even then

a favourable report, but in two days she wanted no telling to keep in bed, for her strength rapidly

declined. Her laboured breathing prevented lying down and taking the much-needed sleep, so that

though towards the last the bronchitis subsided, she could not rally from the trying exhaustion.

She was, however, quite conscious, and gave at intervals loving advice and encouragement to

all who came in, affectionately mentioning a large number of friends and neighbours by name.

About two hours before she died her son brought her father’s Bible and read his favourite Psalm,

the 103rd, which soothed her. A short time before the end she rallied enough to say, “I’m so

comfortable.” Noticing the emotion of her son she kissed him and said, “Don’t fret,” which

were her last words. At 3.30 in the morning on the 9th of Third Month, 1899, she peacefully

breathed her last.

We shall deeply miss her but we cannot mourn. “Not enjoyment and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way,

But to act that each to-morrow,

Finds us further than to-day.”

It would not be out of place to quote what PRISCILLA PITT wrote of her mother, being equally

applicable to herself, viz :- “Who can mourn for such departed ones? Who can have any other

desire than to keep the same faith, if we have received it; and in the love and strength of our

Lord to overcome the world and all its delusive pleasures, the wicked one and all his snares?

So that, like those who have preceded us in the holy warfare, we may go forward conquering

and to conquer. Like choice fruit that continues to ripen till it leaves the tree” – so PRISCILLA

PITT remained bright to the end, being ripe and ready to be gathered.

She insisted on being laid in the same grave with her husband, to whom she had been so closely

devoted for upwards of 38 years, and desired that it might be in the Graveyard adjoining the

Friends’

Meeting House, Park Lane, Croydon, because here her parents and sister, her five

children, and many friends were laid, but feared this was impossible as the ground had been

closed years before. However, as a special favour, and seeing that PRISCILLA PITT was the

longest resident member in Croydon Meeting, the Friends’ very kindly gave their consent.

In the numerous testimonies received by the family after her decease the chief point in her

character referred to was her innate unselfishness and love. It would be extremely difficult to

point to another person in whom unconsciousness of self was more marked. She practically

never wished for self-indulgence, her one idea being to think of the welfare of others. “It was

impossible to be in her company long without noticing how she embraced every opportunity

for the spontaneous exercise of this gift.”

Her nature was affectionate in the extreme. She would often quote the words, “That time is not

lost which is spent in cementing affection.”

Her innocent child-like nature was combined with a fear of giving pain even to the least of God’s

creatures. She would often lift a worm off the path lest it should be trodden upon. Once when

driving a party of friends out into the country she pulled the horse up short, fearing they might

run over a nimble sparrow in the road !

She was not merely truthful herself to a degree seldom attained, but could not even believe other

people were anything else. Even when people used irony, and it was evident to bystanders from

the tone of voice that only innocent dissimulation was intended, she would often fail to grasp

the subtlety, and remark, “I don’t understand thee; I do wish people would say what they mean!

This did not arise from ignorance, for few enjoyed poetry and metaphorical expression more

than herself, but from her perfect guilelessness.

On her death-bed she more than once remarked in a humble way, “I feel that my soul is united

to the Divinity in regard to one thing – my love of truth and honesty.”

If she saw a thing to be right she would do it, whether in season or out of season, regardless of

what people thought of her. Few people were more unconventional, either in dress or address.

Her voice was occasionally heard protesting in Meetings against anything which she felt was

wrong. She believed in Christian simplicity, and could never allow of an admixture with

worldliness. She was exceedingly fond of her Bible, and would frequently, read it to herself,

and also regularly to the household. She knew many passages by heart, and could repeat long

chapters and hymns learnt as a child; at the same time she disliked the criticising spirit which

has lately entered into juvenile Christians who doubt and disbelieve a great portion of Scripture.

She loved early Quaker writings, and others of a deeply spiritual nature. At one time she

translated from the French 16 large books in manuscript for her husband.

In religious matters she was stronger in practice than in precept, seldom talking of creeds or

doctrines. The popular orthodox faith of “only believe” she could not understand, and therefore

could not preach. She understood righteousness that is by faith – to be the doing of all things,

whether eating or drinking, to the glory of God. She felt that God is no respecter of persons,

but he that feareth God and doeth righteousness is accepted of Him. If others could show their

faith without their works she would rather show her faith by her works. At the same time she

had no unity with mere creaturely activity, and said on her death-bed words to this effect, “We

may as well go to theatres and balls as to meetings in support of even philanthropic objects if

it is done out of the Divine ordering. We lay more burdens on ourselves than God lays on us.”

She believed that “the Word” (or Christ) is nigh us, even in our mouths and in our hearts, and

that to obey it is the accepted righteousness. Thus she was not a talker about the Word, but a

doer; and living in that frame of mind she seemed to have a new nature and to possess the Peace

which passeth understanding. She said, “The principles of our profession are opposed to our

making promises in advance, but we should seek for direction at every step.”

When the end came it was not like dying but going home. Those who saw the mortal form

after death remarked that her face seemed to wear a Heavenly calm. The room felt radiant with

glory and happiness. One could hardly help saying, “Let me die the death of the righteous, and

let my last end be like hers.” Then let us remember that we, too, are called to live the life of the

righteous, that our end also may be peace.

JOHN MARSH PITT, SHAMROCK VILLA, MITCHAM, 15th Fourth Month, 1899.

Berkeley Cottage Berkeley House

Berkeley Cottage Berkeley House

Annotated detail from 25-inch Ordnance Survey map of 1895,

showing locations of Manor House, Berkeley Cottage and Berkeley House

ISBN 978-1-903899-65-6

Published by Merton Historical Society – December 2012

Further information on Merton Historical Society can be obtained from the Society’s website

at www.mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk or from

Merton Library & Heritage Service, Merton Civic Centre, London Road, Morden, Surrey. SM4 5DX

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY