A History of Fry’s Metal Foundries and the Tandem Works

Studies in Merton History 12: by Michael J Finch

Studies in Merton History 12: by Michael J Finch

We were delighted when Mike Finch contacted us to ask if we would like to publish his history of this landmark site and the world famous Fry brands produced there and elsewhere.

As he explains in his Introduction:

The task has been made somewhat easier for me because my working life of over forty years started at Fry’s Tandem Works. As a result I have, on my journey, collected a wealth of information about the business and the people who worked there, with help from the monthly magazine, The Fry Record. I also had the memories of five members of my family who worked at the Tandem Works, including my grandfather, who was the works carpenter for 42 years from 1923 to 1965. My mother, Brenda, worked in the wages department from 1953, my father, Tony, worked in the foundry from 1954, and two uncles, Jack and Eric, worked in Fry’s Diecastings from 1942 and 1944 respectively.

Many people who remember the name ‘Fry’s Metals’ may feel the company came to an end when John Fry sold his interest in the company to Goodlass Wall in the 1940s, while others may say it was when the Tandem Works closed in 1991. Whatever the case, the fact remains that the Fry brand is still alive and well today and can be seen on DIY shelves in one form or another. It may not reflect the business of a hundred or so years ago, because the needs of the industry forced the necessary changes that have occurred over the years. The development of metal alloys and fluxes in the early days in particular, and the method of making them, plays a part in many products used today, whether they carry that old familiar Fry logo or not.

This account focuses primarily on the foundation of Fry’s, the companies that existed long before Fry’s that shaped Fry’s future, and the people who made it happen through belief, determination and hard work, not to mention the willingness to take chances. It is a fascinating story of success and a rise from nothing that justifies the effort to tell the story, because there is little information otherwise available. The fact that information is scant is the biggest surprise, given the enormous impact Fry’s Metals had on the print metal industry in those early days, the number of people they employed, not just at the Tandem Works, but also at the branch foundries and overseas, and the impact of the company on local communities.

Michael J Finch

Studies in Merton History: 12

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – 2023

2

Published and printed in United Kingdom by

Merton Historical Society

2023

ISBN 978 1 903899 83 0

Copyright Michael J Finch and Merton Historical Society

In memory of my Grandfather

John Henry Burrage

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Roger Bilham for his advice and detailed research into many aspects of this

book and to Merton Historical Society for their help and advice and making publication possible. I

am especially grateful to Allan MacDonald – Head of HR Business Partners at Element Solutions Inc

(ESI) who own the rights of Fry’s Metals – for the company’s permission to use the pictures.

I would also like to thank Eric Shaw, Terry Cuzner, Walter Davies and Tony Ingham for their

contributions.

The author and the editorial team of MHS have made every effort to check the factual accuracy of

statements made, but in a complex narrative there may be some points that remain open to challenge

or correction.

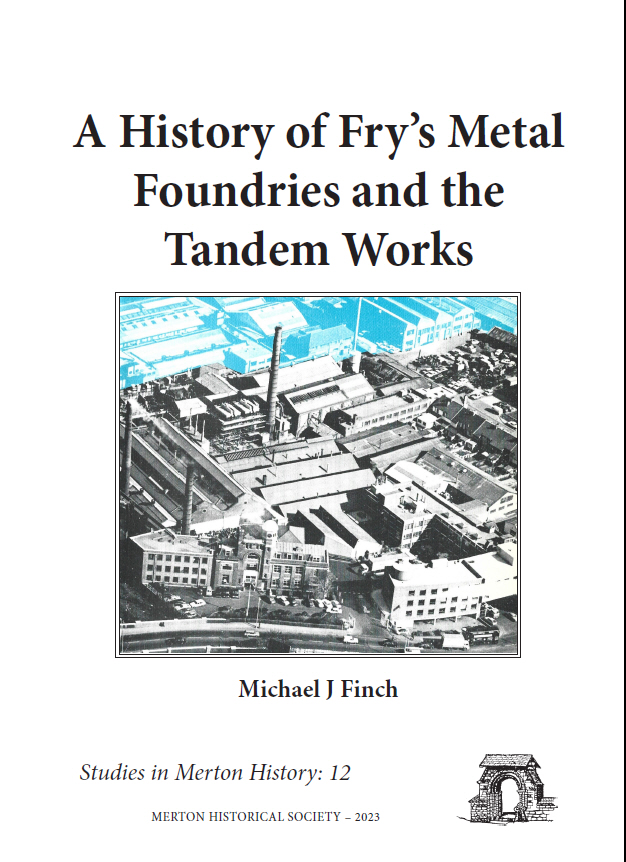

Front cover: This aerial view of the Tandem Works c.1960 formed the main cover in traditional Fry blue for the monthly ‘Fry

Record’. The part shaded blue is beyond the boundary of Fry’s Metals.

3

CONTENTS

Introduction 4

Chapter 1 – Early Years of the Tandem Works 5

Chapter 2 – The Origins of Hallett & Fry 9

Chapter 3 – John Horace Fry 11

Chapter 4 – A Seed was Sown: Holland Street Foundry 13

Chapter 5 – The First World War 21

Chapter 6 – After the First World War 23

Chapter 7 – Fry’s Diecastings Ltd 31

Chapter 8 – The Second World War 33

Chapter 9 – Expansion and Contraction 37

Appendix A – Branch Foundries & others in the Fry Group 41

Appendix B – Mergers, Demergers, Acquisitions & Sell-offs 48

Bibliography 57

Glossary 59

Tandem Works from Christchurch Road c.1960

INTRODUCTION

To research and write a sufficiently comprehensive account of Fry’s Metal Foundries, its origins and

the history of some of the more significant companies within the Fry group has been a demanding

challenge. The task has been made somewhat easier for me because my working life of over forty years

started at Fry’s Tandem Works. As a result I have, on my journey, collected a wealth of information

about the business and the people who worked there, with help from the monthly magazine, The Fry

Record. I also had the memories of five members of my family who worked at the Tandem Works,

including my grandfather, who was the works carpenter for 42 years from 1923 to 1965. My mother,

Brenda, worked in the wages department from 1953, my father, Tony, worked in the foundry from

1954, and two uncles, Jack and Eric, worked in Fry’s Diecastings from 1942 and 1944 respectively.

My grandfather, John Henry Burrage, known as ‘Jack’ to his friends and colleagues, quickly became

a good friend of John Fry, and long after John Fry retired, and until his death, he often wrote to my

grandfather to keep in touch, leaving behind a wealth of letters and information for me to draw on

for this book. Jack became much more than a works carpenter to the Fry staff throughout his working

career, as he was often called upon to mend their shoes, make furniture, toys and desks for their

children, and on odd occasions help them move to a new house by using the company van. He was

also remembered in John Fry’s will for being a good friend and one of many loyal employees.

Many people who remember the name ‘Fry’s Metals’ may feel the company came to an end when John

Fry sold his interest in the company to Goodlass Wall in the 1940s, while others may say it was when

the Tandem Works closed in 1991. Whatever the case, the fact remains that the Fry brand is still alive

and well today and can be seen on DIY shelves in one form or another. It may not reflect the business

of a hundred or so years ago, because the needs of the industry forced the necessary changes that have

occurred over the years. The development of metal alloys and fluxes in the early days in particular,

and the method of making them, plays a part in many products used today, whether they carry that

old familiar Fry logo or not.

This account focuses primarily on the foundation of Fry’s, the companies that existed long before Fry’s

that shaped Fry’s future, and the people who made it happen through belief, determination and hard

work, not to mention the willingness to take chances. It is a fascinating story of success and a rise from

nothing that justifies the effort to tell the story, because there is little information otherwise available.

The fact that information is scant is the biggest surprise, given the enormous impact Fry’s Metals had

on the print metal industry in those early days, the number of people they employed, not just at the

Tandem Works, but also at the branch foundries and overseas, and the impact of the company on local

communities.

Detail from an advertsisement on the inside cover of Fry’s Printing Metals booklet (1936)

CHAPTER 1

Early Years of the Tandem Works

When Herbert F Höveler landed on these shores from Germany in 1891, the treatment in Britain of

metal scrap and residues was in its infancy. At that time, Britain had the first call on plentiful supplies

of ores and virgin metals from many parts of the world, because of her predominance in international

trade, and therefore had not felt the necessity of paying special attention to the re-use of scrap and

residues. It is evident that in those days the average scientist regarded such arisings with contempt.

Non-ferrous scrap metal was used only for requirements of the lowest grade, and oxides and residues

were thrown away as dirt. On the other hand, Germany had been forced by economic pressure to pay

serious attention to the question of metal recovery, and scientists and industrialists in that country had

devised processes and had installed plant for that purpose.

Herbert Frederick Höveler, German industrial chemist and metallurgist, was born 3 February 1859 in

Papenburg, then in the Kingdom of Hanover. He had acquired first-hand experience in Germany in

the treatment of scrap and residues, and found fertile fields in Britain for the development of his ideas.

In 1894 he formed the Tandem Smelting Syndicate Ltd, listed at Jubilee Buildings, 97c Queen Victoria

Street, London EC, and a little later started a small works in south-east London. In this project, he

had the assistance of his old company Höveler & Dieckhaus, anti-friction metal manufacturers, which

had businesses at 74 Broad Street and 3 Stockwell Avenue, London, in tandem with 449 Papenburg

Industriewerk, Germany, trading since 1891 as metallurgical smelters and analytical chemists. It is

believed that the name ‘Tandem’ arose from his intention that the two factories, one in Germany and

the other in England, should co-operate in technical matters. In other words, they should work ‘in

tandem’.

Höveler was a keen and inventive metallurgist and within a few years he claimed to have discovered

metallurgical processes and new eutectics which remain the basis of many present-day practices. The

prospects of business in the efficient treatment of scrap and residues were such that he decided to

build a completely new works and, for that purpose, he acquired land in Christchurch Road, Mitcham,

where today the Tandem shopping centre stands. By 1904 Höveler was residing at 45 Christchurch

Road, Streatham, and rumour had it that, in choosing the site for his new works, the scales were

weighted in favour of the Mitcham location, in the area known locally as Merton Abbey, because of

the identical road name.

The building of the Tandem Works commenced in 1906 and the factory was occupied by the Tandem

organisation early in 1907. The residential accommodation at the Tandem Works from around 1911

was occupied by the works manager, John Menzies, his wife, Annie, and a servant, Florence Cackett,

whilst the Hövelers and two servants occupied their Streatham residence. Mr Höveler was so foxed

by English weights and measures that he stuck to metric and, looking at the plans of the original

office and works buildings, it is clear that he drew up the measurements in metres and left the builder

to make the conversions. In the factory he installed kilo scales and printed conversion tables which

continued through the later years of Eyre Smelting Co. as well as Fry’s Metals. For this reason, come

decimalisation and conversion to metric weights in the early 1970s, Fry’s Metals was a little ahead of

the game.

Höveler was interested in many things other than metals. The Tandem Works soon housed the

Ĉekbanko Esperantista (Esperanto Bank), which he founded in 1907, where deposits and withdrawals

were based on the Spesmilo, devised before World War I by René de Saussure and introduced in 1907.

Esperanto is an artificial language devised in 1887 as an international medium of communication, and

Höveler invented the propaganda ‘keys’, miniature-format newsletters about Esperanto with concise

grammar and vocabularies. The first English version, written with Edward Alfred Millidge in 1905,

appeared in 18 languages by 1912. By the end of April 1914 there were 730 accounts in 320 cities and

43 countries including London, the Madeira Islands, Sicily and Palestine.

Another business carried on in the Tandem Works was the manufacture of a cure for asthma called

‘Vixol’, with the vanillin being extracted from tobacco stalks. There is no guarantee of truth for the

idea that the concoction originated when Höveler found his asthmatic condition was relieved by the

inhalation of the fumes which were emanating from the pots while metal was being cleansed. He is

said to have devised a liquid which, when sprayed, gave off similar fumes. The spraying apparatus itself

was manufactured at the Tandem Works by Charlie Beck, subsequently known as a skilled pot-hand

and a respected member of the works staff. For many years asthma sufferers in various parts of the

world inquired whether supplies of ‘Vixol’ were still available.

Höveler was also a pioneer of the use of oil for heating and developed an oil-burner which was not only

used in the works, but also marketed with some success. It was a liquid-fuel burner for use with furnaces

and boilers and comprised an outer portion, preferably fixed to the furnace or boiler, composed of two

concentric nozzles and a barrel, in which slid an inner portion composed of two concentric tubes, a band,

and an inner regulating needle, the inner portion being held in position by friction only, so that it could

be easily removed for cleaning purposes or when it was desired to replace it. Höveler’s burner patents,

together with burners, spare parts and accessories, were advertised for sale by a controller appointed by

the Board of Trade in The Times of 23 February 1918.

The Tandem Works

Back then the Tandem Works was a very different place. In the early days, the bases of No.1 and No.3

chimney stacks were surrounded by fowl houses, complete with chicken runs, the occupants of which

made regular but involuntary contributions to the breakfast and dinner tables at the Tandem Works.

No.1 stack housed bantams, No.3 stack was at one time the home of turkeys and chickens, while

ducks and geese lived somewhere in the rear. Bacon and fish were smoked over a pit adjacent to No.3

stack, and allotments and pigsties abounded in the area which was in later years occupied by Fry’s

Diecastings Ltd. The perimeter of the works was lined with fruit trees and shrubs, there was a bank of

shrubs along the railway siding, and a grape vine coiled itself around the middle chimney. A narrow-

gauge rail track ran alongside the factory to bring and send materials.

Along the top road that later separated Fry’s Metal Foundry from Fry’s Diecastings there was a row of

apple trees (later cut down and used as greenwood poles for refining). Behind these trees were allotments

belonging to the office staff and workmen, together with a large kitchen garden for the occupier of the

flat over the works in which Mr Höveler used to live at times during his ownership. This garden boasted

fruit of all types, including a large walnut tree, and just outside the laboratory there was a large Victoria

plum tree which bore excellent fruit, and around the far chimney near the smelting shop were hen coops.

The Tandem Smelting Syndicate, Merton, c.1910

The bridge on Christchurch Road, in front of the office block was much narrower than in later days,

with wooden steps on the far side leading to a footpath by the side of the River Wandle, which led into

the High Street opposite Wandle Bank.

In 1914 the name of the English company was changed to the Tandem Smelting Company Ltd,

presumably in order to disassociate the business as far as possible from its formerly desirable German

partner.

Following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Höveler, who was still a German national,

found it difficult to carry on business. Although the majority of shares in the company were held by

enemy aliens, the Board of Trade permitted the continuation of the business because production was

of national importance.

Troubles, particularly of a financial nature, increased, and in the end the business was wound up by

the Board of Trade. The liquidator offered it for sale by public tender, with the result that in 1917 it

was purchased by the Eyre Smelting Company Ltd, manufacturers of antifriction metals. Fry’s Metal

Foundries, who had already started operating their metals business in Holland Street, Southwark, five

or so years earlier, also put in a bid, but it was not high enough.

Herbert Frederick Höveler died at home, 78 South Side, Clapham Common, on 30 August 1918, aged

59. The cause of death was pneumonia with gangrene of the lungs. Two days before he died, he made

a will leaving all of his property to his wife Thekla, who was also the sole executrix. She was granted

probate in February 1919, and the value of the estate was £4,276 3s, equivalent to around £250,000 to

£300,000 in 2020.

Eyre Smelting Co. Ltd

Eyre Francis Wall Ievers was born 10 April 1873 at Tonbridge, Kent, one of eight children of Eyre

Ievers and Jane Perrier née Osburne, who were both born in Ireland. Eyre Francis was educated at

Tonbridge Castle Preparatory School (1880-1884) and Tonbridge Grammar School (1884-87). He

was apprenticed at the locomotive works of Neilson & Co. in Glasgow (1887-1890), following which

he studied at the Crystal Palace Engineering School (1890-1891) and King’s College, London (1892-

1893), while working as an improver at a Great Eastern Railway running shed. In 1893 he went to

Argentina, employed by the Buenos Aires & Rosario Railway as a draughtsman in their workshops at

Campana (1893-1895). For the next two years to 1897 he was a District Locomotive Superintendent,

then Works Manager (1897-1898), Assistant Locomotive Superintendent (1898-1901), and Acting

Locomotive Superintendent (1901-1902). He returned to England

where he was manager of the Eyre Smelting Co. from 1902 to 1904, and

export manager for the Galena Signal Oil Co. from 1904 to 1908. Ievers

made many trips to the USA and Argentina, including in 1904, 1910,

1926, 1931, 1936 and 1939. Together with Harry Pearce, he applied in

1901 for a US patent for a multiple expansion rotary engine, which was

assigned to the Francis Eyre Company of New York.

The Eyre Smelting Company was

established at Tonbridge in 1902 and

had a London address, presumably

the company’s registered address,

at St Helen’s Place, Bishopsgate, and

later at 28 Victoria Street. Products

included white metal bearing alloys

and Bamber’s non-encrusting zincs

(zinc anodes). After the move to the

Tandem Works, the range increased

Tandem Smelting Syndicate advert from 1909 (left) & Eyre Smelting advert

from 1919 (right), reproduced courtesy of Grace’s Guide to British Industrial

History (https://www.gracesguide.co.uk)

considerably. Products included type metal, solder, brass and bronze ingots and castings, and Höveler

liquid fuel burners. Eyre Smelting Co. produced Eyre bearing metal and other white metals, chiefly for

use in railway carriage, wagon and locomotive bearings.

Large tonnages were supplied to the British-owned railways of South America, India and Egypt.

The main production at the Tandem Works for a few years from 1918 was chiefly tin alloy, some

stick solder poured in stone moulds, antimonial and soft leads, some printing metal, and anti-

friction bearing metals for home and export, the main exports being to South American and Indian

railways.

In 1921 Eyre Smelting Co. installed a blast furnace acquired

from the old works on the Thames of the Atlas Metal & Alloys

Co. Ltd, which was taken over by the company (see Appendix

B).

Ievers died aged 84 on 8 December 1958 at his house in

Epsom. There was an inquest on 11 December, at which it

was found that he had committed suicide by gassing himself

while the balance of his mind was disturbed. His wife, Ellen,

had died in 1951.

Eyre Francis Wall Ievers c.1945

Eyre Smelting Co., Tandem Works, c.1918

CHAPTER 2

The Origins of Hallett & Fry

George Hallett & Co. was an old-fashioned antimony-smelting business launched long before the

days of limited companies. It was founded in 1806 as a refiner of antimony, with a foundry south of

the Thames about a quarter of a mile south-west of Blackfriars Bridge, and from 1841 to 1861 it was

located at 52 Broadwall, Blackfriars, near where Waterloo Station now stands.

Hallett’s purchased large quantities of antimony ore from China, Bolivia, Spain and Smyrna in Turkey

and smelted them in contact with scrap iron and some chemical fluxes in plumbago crucibles in high-

temperature furnaces to produce, after three smeltings, what was named ‘Star’ antimony. The star was

the natural crystallisation of antimony and a sign of its purity, and ‘Star’, sold as the oldest brand in the

world, was guaranteed 99% antimony. The smelting of antimony ore and the manufacture and sale of

antimony was Hallett’s main business, with a few minor sidelines that included antimony sulphide for

firework makers and for manufacturing chemists, but their retail trade was comparatively small. Later,

the production of printing metals followed, and they also obtained patents for antimony compounds

in paints.

Over the years, many thousands of tons of ore, packed in sacks, arrived at their foundry, and also

crude antimony, packed in two-cwt. wooden cases, from the Far East and elsewhere. The parcels of ore

were wheeled on a narrow-gauge railway into the smelting works some hundred yards or so away and

stacked neatly in large symmetrical piles near to the furnaces where they were to be fired.

George Hallett invited his godson, Thomas Henry Fry (1845-1920), a budding young lawyer, to join

the firm to help him in the management of the antimony-smelting foundry at Blackfriars. Thomas

Henry, a son of law stationer Thomas Homfray Fry, was to become the father of John Horace Fry, the

founder of Fry’s Metals. The name of the firm was subsequently changed to Hallett & Fry. Thomas

Henry devoted himself to the reorganisation of the whole business, putting it on a paying basis,

including a regular and increasing output per furnaceman, and gradually introducing a few sidelines.

For the staff of about one hundred, wages were low, though considerably higher than elsewhere at the

time, but life was happy. In fact, the work of furnaceman and the regular employment were popular,

and at changes of shift there were always men waiting, hoping for the chance of a job. There was an

excellent relationship between the office staff and furnacemen where the office staff knew their wives

and families, as well as their troubles.

Some ten years later, in 1873, George Hallett, who had an address at 296 Rotherhithe Street, died, and

for a while Thomas Fry managed the smelting business alone. Later on, owing to one of their side-

lines, ‘artificial manure’ (heaven only knows what it was!) emitting unpleasant odours, the firm was

obliged to transfer its manufacture to new premises at 202 Rotherhithe Street, on the south bank of

the Thames two miles below London Bridge, where they successfully carried on smelting ores which

arrived by barge from various London docks.

A few years later, in 1877, Alexander Miller (born in Paddington in 1856, died 1953), a friend of the

Hallett family, joined the firm, changing his name to Alexander Miller-Hallett for inheritance reasons.

In 1892 Miss Emily Caroline Hallett, the sister of George Hallett, bequeathed her fortune and her

antimony business based at Norway Wharf to Alexander, and he thereby acquired an extensive estate

at Goddington, (between Orpington and Chelsfield) in Kent, comprising a mansion with a dozen or

more retainers, lodges, woodlands, a farm with a prize herd of Jersey cattle and fine pedigree stock. He

had his own cricket team and occasionally travelled to Rotherhithe on horseback, 12-15 miles each

way and he was likened to the country squire, as he attended the London Metal Exchange daily with

silk hat, morning coat, gloves, buttonhole and walking stick. Quite a sight, even in those days!

Most of their buying and selling was done on the London Metal Exchange, which had originally been

established in Lombard Court in 1877 as the London Metal Market & Exchange. After 1880, the

United Kingdom changed from being a nett exporter to a large importer of metals. With improved

communications, news of shipments of goods arrived before the actual metal, and merchants could

offer material at a certain price with definite delivery dates (futures), so the LME was created to

rationalise the situation. It later moved from Lombard Court to the Old Jerusalem Coffee House in

Cowper Court and afterwards to Lombard Street. On 30 July 1881 the Metal Market & Exchange Co.

Ltd was incorporated, and in 1882 this company moved to Whittington Avenue, once the site of the

Roman forum.

There were no chemists or metallurgists in Hallett’s, for they were considered rare and costly creatures,

and the manufacturing process was carried on by rule of thumb for over a hundred years, though

times were changing and progress was in sight. Chemical analyses were costly and usually took a week

to get results and so were avoided as much as possible. Professional analysts were only employed to

check qualities between seller and buyer, with three well-known companies for that group of metals:

F Claudet in Coleman Street, E Riley, and later Edward Montague. The first two charged one guinea

for a single element for alloys, five guineas for the antimony content of ores, and five guineas for a

complete assay. Montague later competed with the well-established firms at about half their charges,

and sometimes Johnson Matthey (bullion company) was used.

The work at Hallett & Fry was very hard, and furnacemen worked from 6 a.m. to 5.30 p.m. Monday

to Friday and 6 a.m. to 12.30 p.m. on Saturday. On nights the men worked 60 hours per week, in five

12-hour shifts. The furnaces were lit at midnight each Sunday and burned until midday the following

Saturday. They were then let out, to reline and repair them, so that they should always be kept in good

working order. In order to withdraw the crucibles from the furnaces, the men first pushed back the

sliding cover made of red Welsh tiles. Straddled across the furnace they fixed the tongs carefully to

the top of the crucible and lifted it some four feet or so prior to tipping the molten, almost white-

hot, contents into the cast iron moulds. Frequently the men’s gaiters caught fire after this operation,

which they performed 30-33 times per shift and which must have been doubly uncomfortable during

summer.

At 202 Rotherhithe Street it must have been quite an interesting sight on a summer’s day to see the

antimony ores arriving by barge on the Thames and to see the barges or lighters swung into position by

tugs right out in the river, so that they would gradually drift into the correct position for unloading at

Norway Wharf, right under the two cranes awaiting their arrival. Even more exciting must have been

to watch this performed in a strong tide. From 1904 to 1908 the Rotherhithe Tunnel was built beneath

the factory, and in 1907 the LCC agreed to pay Hallett & Fry £800 for easement under the premises

and water supply, with more to be paid if there was any damage caused by the tunnel within two years

of its opening. The site of Norway Wharf is now occupied by Horatio Court, built during the 1990s.

CHAPTER 3

John Horace Fry

(13 May 1876-6 September 1967)

John Horace Fry was born at 282 New Cross

Road, Hatcham, the left-over name of a

medieval manor in the parish of Deptford.

He was one of six children to parents

Thomas Henry Fry and his wife Emily, née

Dannit. As we have seen, Thomas Henry

Fry started his metal career as an antimony

refiner and manufacturer of similar alloys at

Broadwall, within a quarter of a mile from

the later Holland Street foundry. He died

on 10 November 1920, naming three of

his sons as executors. His address was The

Elms, Belmont Hill, Blackheath, and he left

£46,043, equivalent in 2020 to about £2.25

million.

John was a cousin of the Fry family of Bristol,

where a young Quaker physician, Joseph Fry,

had begun around 1753 making chocolate at

his apothecary’s, which was the beginning

of J S Fry and Sons, possibly the oldest

chocolate firm in the world. Joseph Fry

also went into typefounding around 1764,

forming a partnership in the Bristol Letter

Foundry with printer William Pine for the

Bristol Gazette. His sons Henry and Edmund

later went into the typefounding business

with his widow, Anna.

On 1 May 1894, a fortnight before his

eighteenth birthday, John Fry joined Hallett

& Fry as a junior, almost straight from

Eastbourne College, where he had been reasonably successful in his education and particularly

enjoyed being on the sports field. John Fry’s eldest brother was born in 1873/4 at New Cross and was

christened Thomas Hallett Fry, but he did not join the antimony business and died on 7 July 1910.

Rotherhithe could be a pleasant enough spot in those days, and John Fry found plenty of interest in

the laden barges and other river traffic, whilst supervising the weights of incoming crude antimony,

antimony ores, etc. Towards the end of 1899, at the age of 23, he left home and Rotherhithe for nearly

two years to join the 69th Imperial (Sussex) Yeomanry in the South African, or Boer, War. He was

present early in 1900 at the early surrender of Johannesburg and Pretoria to Lord Roberts and Lord

Kitchener, subsequently fighting in the veldt against Generals Smuts, Louis Botha, De la Rey and

other Boer leaders in the Transvaal. He rejoined Hallett & Fry at Rotherhithe in October 1901 and

the business continued successfully for the next few years under the equal partnership of his father,

Thomas Fry, and Alexander Miller-Hallett.

In 1909-10, after 47 years’ service, his father wished to retire from active participation. Being an old-

fashioned concern, there were no shares and no very definite rules as to how to deal with matters of

partnership, particularly resignation and so on. There were conversations, disputes, delays, and finally

The English painter Mr. Francis Hodge painted the

portrait of John Fry. Mr. Hodge had the distinction of

painting portraits of His Majesty King George VI, the

Archbishop of York, Field Marshal Montgomery, and

in 1946 had two of his portraits exhibited at the Royal

Academy. A copy of an oil painting presented to John Fry

by the staff upon his 70th birthday.

Thomas Fry retired in 1911 without having been able to make any satisfactory agreement concerning

the succession to his half-share of the business. Alexander Miller-Hallett did not make it easy, and

after a long association he felt he would like to become the sole proprietor of the business. Owing to

the loose terms of the original partnership, the only promise Thomas Fry was able to obtain was that in

due course, when Alexander Miller-Hallett wished, his son, John Fry, would be given the opportunity

to purchase a shareholding similar to that of Alexander’s eldest son, George, so that eventually they in

turn would become equal partners. No price was discussed, and so it was by no means a satisfactory

arrangement from young John Fry’s point of view. Meanwhile, George, educated at Rugby and Trinity

College, Cambridge, joined the firm as its junior member in 1906, after spending a year in Angers, in

France, and in spite of his father’s attitude he and John Fry always remained good friends.

There were then three junior partners – John R Hollingworth, joined 1887, John Fry joined 1894 and

George Miller-Hallett, joined 1906. With his colleagues, part of John Fry’s duty was to inspect all

the metal produced, including the manufacture of ‘Star’ antimony and printing metals. They helped

with the mixing of the ores and the subsequent blending of the metal, so as gradually to leave all

the sulphur and iron behind in the slag. A simple elementary process, with no guile, or chemists or

metallurgists on the staff, but it produced a beautiful crystalline ‘H’ brand ‘Star’ antimony over many

years – and handsome profits, too. With very little chemical experience, they could all be proud of this

old-fashioned Thames-side business, and they became experts in quality control.

After Thomas Fry’s retirement, John Fry accepted a three-year agreement. Less than a year later, in

late 1911, finding that the position was becoming difficult, and feeling that the outlook offered little

promise of progress or opportunity, he approached Alexander Miller-Hallett and discussed the whole

situation with him in a frank and friendly manner. Miller-Hallett met John Fry in the same spirit, but

was quite determined to run the business in his own way and for his own benefit, and was not prepared

to make any changes or concessions. John Fry told him quite openly that he believed he knew how to

develop one of the sidelines, printing metals, and asked him for a half-share in this one direction only.

Miller-Hallett would not discuss the matter, nor would he permit John Fry to make any special efforts

to introduce new sales methods, as advertising was also frowned upon as being undignified and in

bad taste. He told John Fry that he and his father had been partners for many years and now he would

like to become sole proprietor for a while and had no intention of sharing any part of the business.

When in turn he wished to retire, he would agree that his son George and John Fry might eventually

be given the opportunity of becoming equal partners. John realised that this might be years ahead. In

fact, Alexander Miller-Hallett lived to the age of 98 – another 42 years!

John Fry could see little daylight ahead and the outlook was grim. Living with his young wife at

18 Eliot Park, Lewisham, his occupation recorded as ‘antimony refiner’, he realised that it would be

wise to examine the position carefully. After serious consideration, partnership not being available, he

asked to be released from the agreement, to which Miller-Hallett readily agreed. John Fry reminded

him that, as his early training had been in metals he might, to some extent at any rate, become a

competitor in their principal sideline, though not actually in the smelting of antimony. They were then

selling 100-150 tons of antimony and 15-20 tons of type metal per month and Miller-Hallett at that

time might have had, practically for nothing, a half share in the Fry’s Metal Foundry business which

was about to emerge.

After John Fry’s resignation in 1912 the name of the firm was quickly changed to Hallett & Son, the

Fry name disappearing after some fifty years.

CHAPTER 4

A Seed was Sown: Holland Street Foundry

John Fry had no very definite plans, only ideas, but was already turning things over in his mind. For

some three years previously he had been attending evening classes in metallurgy and chemistry at the

Northampton Institute in Clerkenwell, under the direction of Alfred Holly Mundey (1868-1951), in

charge of the Metallurgical Section, a kindly gentleman and an expert in chemistry and metallurgy.

John Fry studied the practical nature of metals, the assaying thereof, and under Mr Mundey’s valuable

and sympathetic guidance learned for the first time something of specific gravity, melting points

and other properties of the various metals, and was also introduced to eutectics. Mr Mundey’s full-

time work was at Woolwich Arsenal where he was a foreman, which in those days was probably

comparable with being a foundry manager in commercial life. He spent about three evenings a week

at the Northampton Institute to improve his income, and he and John Fry became good friends. On

the evening of 27 November 1911 Mrs Fry met them on the way home from the institute, and they

stopped for some light refreshment, to rest and to discuss the changing situation at Hallett & Fry. John

Fry outlined his early thoughts in regard to the possibility of starting a new business, and his wife

supported him wholeheartedly, enthusiastically and very courageously, as it meant risking their whole

economic future. In the event of starting, he asked Mr Mundey whether he would like to become

consultant metallurgist at a modest fee, to which he readily consented. A lucky day for John Fry.

So it was that in a meeting on 27 November 1911 between John Horace Fry, Nancy Louise Fry and

Alfred H Mundey, they made the decision to launch Fry’s Metal Foundry. After leaving Hallett’s there

was no time to be lost. For the next few weeks, John wandered, and sometimes cycled, through the

streets on the south side of the Thames in the neighbourhood of Blackfriars Bridge, visiting many

empty properties, chiefly old and derelict. He found quite a small foundry at 25-27 Holland Street,

Southwark, just a few hundred yards across Blackfriars Bridge from Fleet Street. It was a vacant, dark

and very limited property by Falcon Wharf and Falcon Drawing Dock, previously used as a small

bronze and brass jobbing foundry, then called the Falcon Brass Works, and once responsible for the

assembling and finishing of the iron railings outside St Paul’s Cathedral. Where the wharf met the

north end of Holland Street had previously stood the Falcon Tavern which Samuel Pepys visited.

Holland Street was off the beaten track yet sufficiently close to Blackfriars Bridge and to Fleet Street

to be interesting. John Fry thought it capable of producing between 1,000 to 2,000 tons per annum

and making a possible profit of £2 to £5 per ton, which in those far-away days seemed a reasonable

proposition.

The Holland Street premises belonged to Alderman Sir William Treloar, carpet salesman and ex-Lord

Mayor of London, with a large thriving business in Ludgate Hill near St Paul’s Cathedral. Holland

Street was named after Lord de Holland, a favourite at the court of Queen Elizabeth I. At the south

end was a dairy complete with cows, and a little way further on a warehouse and house belonging to

the Treloars of Ludgate Hill. A little further on past Nos. 25-27 you came to Castle Yard, named after

an old coaching inn of Victorian days, occupied by Sennett Bros, fur merchants, one of whom was a

knight and a sheriff of the City of London.

John Fry sought an interview and was offered a lease – twenty-one years at £100 per annum. He

realised this would make rather a big hole in his small available capital, which had to be protected with

great care. As John endeavoured to obtain a reduction in rent, Sir William, a wise man, countered with

seven years at £90 p.a., then seven years at £100 p.a. and finally seven years at £110 p.a., which John Fry

accepted. But this rent had to be earned – and quickly!

John Fry’s mind was busy with possibilities for the future, but his name was not yet known in the

printing industry. Being a modest sort of person, he would probably have settled on something more

impersonal, but Mr Mundey suggested that John Fry’s name should be associated with the new firm,

and so it became Fry’s Metal Foundry.

25-27 Holland Street were originally ancient cottages and John Fry knocked out the ground floors and

installed a dross furnace and a couple of melting pots. The offices where Mrs Fry kept the books were

on the rickety, sloping two floors above, and John Fry was his own manager and executive.

The rate of progress may be gauged by

noting that further freehold premises in

Holland Street were added: No. 30 in 1913,

No. 29 in 1914, No. 26 in 1915, No. 42 in

1918. On 1 January 1920 Fry’s opened

a new foundry at 32-42 Holland Street,

together with an experimental foundry

and chemical laboratory. Three separate

groups of premises combined to form the

London works, and the headquarters had

been rebuilt and extended to form a model

foundry and offices. The new buildings

were designed by architect Reginald C Fry,

winner of the Daily Mail Ideal Homes Exhibition at Olympia in 1911, and brother of John Fry.

The Fry’s Foundry premises at No.42

comprised two double-storeyed

parallel buildings connected by an

apexed roof of glass covering the main

foundry, opening on to the entrance

yard and terminating in a fine clock

tower with four dials. The clock was

synchronized hourly from Greenwich

and illuminated at night. Anyone

within sight was not likely to miss

these dials at night, or the name of the

foundry cast in shining white metal

letters, as befitting the firm’s activities,

which were suspended upon a tall wall

facing the entrance.

In those early days in Holland Street the neighbourhood had some very distinctive smells, such as

Kohler with his foul-smelling

printing ink driers. He used

to mix up his contents on the

ground floor right below the

cashier’s department, and in

one of his department’s rooms

he stored his tins of Golden,

Aurol, Flintol and Blackol,

which all smelt the same. This

was flavoured by Mrs Trent’s

breakfast aroma of bacon and

eggs, also from the ground floor.

Mix all this with the smell of re-

melted tin, lead, Wakeley’s hop

manure and Epps’s cocoa and

you could enjoy the aroma from

as far away as Southwark Bridge.

Front entrance of Fry’s Metal Foundry 42 Holland Street,

Blackfriars, 1919

The office staff at Holland Street, Blackfriars, foundry.

John Fry front centre. c.1919

The workforce at Holland Street, Blackfriars, foundry. c.1919

J Bowbrick & Sons, a Southwark firm of builders,

was called in to prepare the foundry for melting

pots, concreting a considerable area and, later on,

building their first reverberatory furnace from

plans prepared by Mr Mundey. The Bowbrick

brothers were a great help in launching the new

foundry which, with their limited experience,

took quite a time to get into satisfactory working

order. Roger Bowbrick was born, one of thirteen

children, on 9 March 1887 in St Saviour’s

parish, Southwark, to John Bowbrick, a house

decorator, and Annie, his wife. In September

1913 he married Violet Florence Turner at the

Southwark Register Office and was by then a

journeyman metal founder.

Like Roger, Violet was a south Londoner, in her case from Camberwell. His son John, known as Jack,

became a metallurgist at Fry’s Metals, where he was living with his parents in 1939. He gradually

became a source of strength in the foundry, continually experimenting in all directions under Mr

Mundey’s guidance, removing impurities from metals and furthering any new ideas which came along.

Roger died at his home in Sutton of various heart complaints in 1978, just before his 89th birthday.

Violet survived him until 1983. Miss A F Bowbrick also served loyally in the clerical department for

many years, and her two brothers worked occasionally in the foundry.

The foundry itself had a well-equipped chemical laboratory on the second floor, then presided over

by ‘Pa’ Davidson, late of the Great Western Railway, assisted by Ernie Baker and George Berry. On the

ground floor there was a model foundry for experimental work, eight two-ton gas-fired melting pots,

one seven-ton melting pot, a tilting crucible furnace for high temperatures, and more than a dozen

other furnaces of different patterns and dimensions around the perimeter, the offices being one storey

up, directly over the pots.

The policy began of providing customers with a free and frank technical service, a policy which was

something of a rarity in those days, when a supplier rarely evinced much interest in his products once

they had left his works.

John Fry had an enviable ability of finding and encouraging young men to work. In the first handful

of recruits were P M Parish and G W Gibson, who over 30 years later became chairman and managing

director respectively. In the office was John Fry himself, chief office manager, secretary and cashier;

buyer of (scrap) tin, lead, ‘Star’ antimony (from Cookson), and ingot tin; traveller, salesman, mixer of

metals, etc. W Leslie Sarjeant (still in his teens, and a distant relative by marriage of John Fry’s elder

brother) straight from Felsted School, Essex, was the assistant, with a typewriter which he was still

learning to use. A lively little cricketer, likeable and friendly, he died during the run of the Printing

Exhibition in 1929, aged about 34.

In the foundry were Sydney Chambers and Ted Moss, two untrained local youths both in their teens,

and Roger Bowbrick joined them a few months later. C S Rowden joined them in 1916, and Mrs A M

Hallett in 1918.

John Fry had five brothers, but unfortunately none was able to join him in his interesting adventure,

though most helped Fry’s Metal Foundry progress in one way or another. In the early days, architect

Reginald Cuthbert Fry, who resided at a boarding house in Eastbourne, planned and guided the erection

of larger premises, built at the end of the 1914-1918 war on the opposite side of Holland Street, and

he was always ready with advice on architectural, building and practical matters until his early death

in 1935. Engineer Sydney Norman Fry, (the founder and proprietor of Fry’s Motor Works and agent

No. 25 Holland Street, Blackfriars

for acids) was their first engineer

and he introduced the valves for

the bottom-pouring melting pots.

Sydney resided with his mother

at the Old Ship Hotel in Brighton.

After an early difficulty, under his

guidance these valves were gradually

installed in melting pots in all the

foundries, as they acquired them,

making a significant improvement.

Edgar Vivien Fry, then managing

director of Kemball, Bishop & Co.,

chemical manufacturers, gave them

useful and profitable orders for

metal ‘eggs’ (large containers used in the manufacture of tartaric and citric acids), and Wilfred Thomas

Fry (income tax accountant), the youngest brother, advised and helped on income tax and financial

matters, a business which he had inherited from the eldest brother, T Hallett Fry.

So, almost unknown in the industry he had chosen, in July 1912 John took down the shutters and

started off, with little money, a few tons of lead, tin and antimony, and no actual orders, but his plant

was handily situated in Blackfriars, not far from Fleet Street, then the home of the English newspaper

industry. Only one order was even promised to him, by his godfather, Horace Cox, who was then the

proprietor and editor of Field and Queen, of Breams Buildings, EC, a school friend of his father’s. Later,

he had to fight to retain even that order. The first accounts of Fry’s Metal Foundry, for the six months

to 31 December 1912 show a capital of a mere £3,000, and the turnover for the first six months of

business came to the princely sum of £2,397 16s 3d. The wages entry conjures up visions of sweated

labour, as the total bill for six months was only £42 17s 10d. The total plant and machinery cost

amounted to £402 18s 8½d. Profit was £23 17s 0d.

They were indeed venturing into the unknown, and economy was essential if they were not to founder

on the rocks in less than twelve months. Generosity was impracticable, as everything had to be acquired

and paid for, and all out of their limited capital of only £3,000 borrowed from his father.

Manufacture of printing metals

John Fry soon realised that with Hallett & Fry’s 200 tons per annum he had only been touching the

fringe of possibilities in the printing and newspaper world. Stereotype was already in use, invented in

1750-51 by William Ged, a goldsmith from Edinburgh, using a plaster of Paris mould, later superseded

by papier mâché. Stereotype was a fixed type

in the form of a plate, upon the surface of

which was a cast of a reproduction of the

faces of all the type which had been set up by

the compositor, together with any pictorial

matter which was to be printed. Linotype,

Monotype and other typesetting and type

casting machines had only recently arrived

in most newspaper works.

The actual manufacture of printing metals was

still in its infancy. In addition, the newspaper

industry was badly served by several second-

rate metal firms, and none of these, John Fry

and Mr Mundey were sure, understood the

Early team members at Holland Street

The Daily Telegraph Linotype machines running Fryotype

science of metallurgy and the best

methods of mixing alloys, or the

correct percentages which were

necessary for the comparatively

new machines. At the bookstall on

Charing Cross Station the young

salesman was intrigued by Mr Fry’s

constantly asking him to procure

a copy of every daily newspaper in

the British Isles. He enquired why

he wanted them, and when he told

him he wanted to learn the names

and addresses of all the proprietors

and printers, he suggested he should

buy a copy of Willing’s Press Guide,

which he promptly did. Fry’s Metal

Foundry was already another important step on the way, and that young man could never know how helpful

his suggestion proved to be. Willing’s Press Guide gave John Fry much useful information, and ideas too. It

became the basis of their valuable records department. Later Kelly’s Directory of Printers and the Post Office

Directory of Trades were regularly used by ‘Records’ and for their advertising campaigns, with excellent results.

John Fry, who came from a family of antimony refiners, realised that there was ample scope for the

manufacture of printing metals (alloys of tin, antimony and lead) using sound metallurgical principles

coupled with a deep knowledge of the requirements of the printing industry. His venture became a

success and the blue horse-drawn carts of Fry’s Metals soon became a familiar sight on Blackfriars

Bridge as they hauled their loads of metal ingots to Fleet Street newspapers, printers and foundries on

the other side of the Thames, and returning with scrap type for refining back at the works.

During the first years, Mr Mundey used to come from Woolwich Arsenal on Friday evenings to see

how things were progressing, and it must be borne in mind that in those days they had no knowledge

about the removal of impurities from the type metal, such as copper, zinc, etc. There was no laboratory

at the start and the method was to take two samples very carefully which were then sent to Montague

Brothers, who generally let them have the results the following day. As time went on, they were getting

many more orders and had more lads in the foundry, who were very useful in delivering metal to

the city by hand truck. The system was five cwt. for one boy, ten cwt. for two boys, and for larger lots

they sometimes hired a horse van. On several occasions John Fry drove his brother’s horse and van to

deliver metal and collect dross himself.

Fry’s had a fleet of three horse-drawn vehicles, one

lorry and a tricycle, but they gradually hired attractive

blue delivery vans and white and grey horses from E

Wells & Son, of Rotherhithe. Motor cars were gradually

arriving on the streets, but horse and van were more

economical. Their carmen wore smart blue uniforms,

first one driver, then two, gradually half a dozen or more

– smart-looking men – and as the years progressed,

they began to be noticed in Fleet Street, and generally

in the land of printing. The carmen were representatives

of the firm and took pride in their vans, and particularly

in their horses, which competed in the annual Cart

Horse Parade and regularly won prizes. Around 300,000

horses were on the streets of London in the early part of

Advertising in the early days

Holland Street horse-drawn delivery

the twentieth century, and the Cart Horse

Parade, an initiative to encourage owners

to take better care of their horses, was

established in 1885. The first parade was

in Battersea Park and took place on Whit

Monday. A second annual parade called

‘Van Horse Parade’ started in 1904 on Easter

Monday with the Cart Horse Parade moving

to Regents Park in 1888. The Cart Horse and

Van Horse Parades merged to be one single

annual parade in 1966. The parades still take

place today but alas no longer in London.

As even the horses could not work 24 hours a day, the company acquired a neat little hand truck, and

promised and made prompt delivery, by pulling all the ingots by hand through the streets. On urgent

occasions, one or two of their enthusiastic office staff were known to lend a helping hand with delivery

by aiding as second or third assistant, pulling this heavy load up the somewhat steep slope from

Blackfriars Bridge towards Fleet Street and the neighbourhood, where the printers, Fry’s customers,

dwelt in considerable numbers, and were waiting for their metal.

The same carmen stayed with Fry’s to drive the motor vans, first small two-ton vans, gradually

progressing to 5-10 tonners. Fry’s Metals were proud of their delivery fleet, and so were the drivers.

An attractive advertisement! It is worth mentioning at this point that from 1946 until his retirement in

1984, Fry’s driver Dick Roberts drove a total of 840,000 miles delivering for the business.

Meanwhile, office furniture, filing cabinets, carpets, etc. were arriving at the Holland Street premises

and careful thought and attention were given to such things as notepaper design, whose quality and style

were to be the best they could afford, so as to try and attract attention and to be an early advertisement

for them. As the company was unknown, such trivial matters were important to John Fry and he

knew that there had to be intelligent and attractive advertising. (Hallett & Fry had been altogether

too dignified, and maybe complacent, to seek business and never advertised.) Fry’s Metal Foundry

set out on an entirely different plan and everything was done modestly to attract attention. Gradually

John Fry made himself known to editors and proprietors of all the printing trade journals through his

personal contact and later friendships with Harry Whetton, editor of British Printer, William Liberty

Field (father of ‘Billy’ Field, of Hoe’s Printing Presses), the editor of Printers’ Register, and Charles

Baker, editor and proprietor of Newspaper Owner, subsequently Newspaper World. It was he, a kindly

old gentleman, who suggested to Mr Fry that they should coin and use the word ‘Fryotype’, which they

promptly did, with considerable advantage. Stonehill & Gillis, proprietors of British & Colonial Printer

& Stationer, also became good friends and were very helpful and encouraging in those early years.

Holding, as they did, a comparatively small proportion of the increasing printing metal trade, they

quickly realised that there were considerable opportunities for development within the more important

world of newspapers in the Fleet Street area, and also with the provincial dailies, by acquiring and

introducing to the trade more chemical and metallurgical knowledge of alloys and the recovery of

oxides, as well as general technical skill and knowledge of printing requirements.

Technical and commercial progress

John Fry was sometimes asked why Fry’s Metal Foundry made such rapid progress. It was a difficult

question for him to answer, but he would say: largely concentration, perseverance and luck (perhaps

90-95%, with just a sprinkling of ‘the indefinable’, say 1%). John Fry liked to quote Julius Caesar

with ‘There is a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune’. The position

(Holland Street), paying promptly, turning over their capital rapidly many times a year, the records

department and expert technical representatives, reasonable prices for ‘Fryotype’, quality, reliability,

Delivering ‘Fryotype’ printing metal from Holland Street to the print

industry. The Epp’s Cocoa Powder sign still evident on the building wall.

and the knowledge and use of eutectics, were all a good recipe for their success. Recovering of dross,

exporting, and a research department, undoubtedly helped them to establish and enhance their

growing reputation in the field of printing metals and white metals.

The trade realised they were experts and not just rough and ready metal mixers, such as had formerly

served them. Until Mr Fry commenced in the business, little was known of the properties of printing

metals, although approximate compositions for the metals required for the different machines

had become established by custom and use. Mr Fry saw the need for a scientific approach from the

metallurgical angle, and he formulated the policy of studying the requirements of the trade, which was

followed ever afterwards. He and his staff investigated the physical properties of the alloys needed for

the different types of composing machines in stereo plants, the effect of the properties of tin, antimony

and lead in the metals, the harm which certain impurities could cause in working conditions, and the

way the metal flowed through the machines. Whilst the machines that cast the characters so quickly to

an accuracy of one thousandth of an inch were real miracles of production, their output would not have

been possible without the actual print metal. The information was passed on to the trade by lectures

(particularly by Mr Mundey), by articles in trade journals, and through the representatives and sales

staff. In 1936 the first edition of their book Printing Metals was produced, and this was accepted as the

standard work on the subject within the industry. It should be added that all the characters produced on

these machines were subsequently re-melted and the metal used again and again.

In 1914, much as in the days of Hallett & Fry, life wasn’t too easy in the foundry, as the hours were very

long – 6 a.m. until 6 p.m. weekdays and 6 a.m. until 1 p.m. on Saturday, but after a while they changed

to a 7 a.m. start. It was a whole day’s work to pour one pot, as each round was poured at a specified

temperature and, as the pots were coke-fired, that often proved awkward. The method of pouring was to

fill one round of moulds and then, when they were set, to put more moulds on top and carry on like that

until the pot was empty, which took four rounds, with the pot being stirred the whole time. Each ingot

was then trimmed at the ends with a hammer and carried to the scale, which could only weigh ten cwt.,

and then the finished batch was numbered and stacked in a cupboard. All this was done by hand as, at

that time, they had nothing on wheels to help them. After a while, they had a four-wheeled truck and a

couple of sack barrows, and this made work much easier. The pots were built high to enable the pourer to

take the four rounds of moulds and they had a long spout with the valve setting in the bottom of the pot.

The firm was very particular with packaging and, if ingots were sent in sacks, they were first carefully

laid in a new sack and then sewn up with the label attached. If a cask was needed, it was stencilled ‘Fry’s

London’ on one end and a label on the other. The antimony used to come from Cookson’s, one ton at a

time, and the tin, which they had in five-cwt. lots, was collected by truck from the wharf by Southwark

Bridge. For the five-ton order from Amalgamated Press in Lavington Street close by, they started very

early in the morning and delivered it with a borrowed truck and their own truck, and stacked it on the

pavement, so by the time their customer started work, the whole five tons was there waiting.

Once Roger Bowbrick married in September 1913, he and his wife, Violet, lived on the premises at 25

Holland Street, so that each evening at 9 p.m. he could go downstairs to the furnace room and bank

up the fires ready for the next day and also keep a watchful eye on the furnace, to make sure it was

working. He performed this task for many years every evening before a working day.

The Printing Exhibition, held in June/July 1914 at the Royal Agricultural Hall, Islington, and later at

Olympia, was excellent publicity and a considerable help to Fry’s development. Fry’s had a small stand

by the gangway, and the only other printing metal firm exhibiting was T G & J Jubb, who had quite a

large stand in the centre of the hall. The Fry stand was tastefully furnished in the ‘Fryotype’ colours of

blue and silver, with ample space to welcome and entertain visitors. Added attractions were a section

of a laboratory in action, with a mock-up of a working foundry unit and the respective assistants busy

interviewing their customers. There was a series of these printing exhibitions every four years, and of

course other exhibitions too. Things were progressing well and by 1916 John Fry and his wife Nancy took

up residence at 9 Victoria Street, Westminster (by 1951 their address was 10 Albion Gate, Hyde Park).

Holland Street casting shop,

c.1914

Holland Street casting shop,

c.1920

The Leads Department, c.1918, showing rolling

and casting machine.

Holland Street Store, c.1920

CHAPTER 5

The First World War

World War One changed the direction of production to bullet metal to help the war effort. During the

early days of the War, Fry’s rented, at a very reasonable rate, an empty shop on the north side of Fleet

Street between Chancery Lane and Fetter Lane to display their goods. As they had been in existence

for only a little over two years, the First World War hit Fry’s quite hard. The government imposed an

excess profits duty of 50% rising to 80% by 1917, to be levied on profits in excess of pre-war standards.

They hadn’t yet fully established themselves, and had only just succeeded in reaching three figures

of profit, in 1912-13 of around £250, but they were paying their way, learning at the same time and

making progress. There were the inevitable wartime ‘controls’ to harass them, and office staff P M

Parish, V C Woodroffe, P J Ross, J W Peters, G H Marks, P W Sleigh, F Mitchell, M J O’Riordan, S O

Johnson, S C Davidson, G V Maddams and W Moneta, and many of the foundry staff too, left to join

the war.

All this was a real blow

to such a young firm and

hardly the promising start

they wanted. But even

though they could not

earn profits, they learned

to develop and to handle

considerable quantities of

metals, to increase output

and cover a wider field.

The government badly

needed output, and large

orders were thrust upon

them at a fast pace. As

manufacture of shrapnel

bullets increased, chiefly

for Walker Parker (who

became part of Associated

Lead Manufacturers and

subsequently the Cookson

Group), two more two-

ton pots were put in on

the ground floor of No.30

and were kept very busy. A

few additions were made

in the office. After a little

while, Lane Brothers of

Rotherhithe came along

with a machine for making

shrapnel bullets. This

should have made about

500 bullets at each charge,

but it was full of snags. The

moulds were inefficient and were not producing good castings, and as a result output was slow and

costly. They soon returned to the production of bullet metal, which reached heavy tonnages. Fry’s

Metals may not have been making large profits, but the war did, if nothing else, enable them to think

Roll of Honour of staff members who served in the First World War

big. Large deliveries were required, and Fry’s had to provide them. Large stocks, and overdue payments,

were left on their hands for considerable periods of time, which was difficult to cope with. In normal

times payment in advance was necessary, which with small capital of course limited progress, but in

wartime this position was reversed.

The sales of melting pots soon reached 1,000 and they introduced dross containers, a considerable

improvement on the sacks, which were very unhygenic and inefficient. ‘Fryotype’ thermometers for

testing the temperature of molten metal had also been sold in large numbers.

They were working night and day at full capacity and at the same time bombs were falling. The government

also requested all newspapers and printers to surrender as much type metal as possible, and with a small

staff continually depleted by the demands of army and navy they were kept extremely busy. On one

occasion a Zeppelin caused considerable damage in Holland Street, and several girls in a neighbouring

tea factory, less than a hundred yards away from Fry’s, lost their lives. To add to the hardship, on several

occasions the Thames overflowed its banks and swept downhill towards the Holland Street foundry and

they only just managed to escape disaster with the help of the erection of tide boards.

As if things weren’t hard enough in those war years, with a number of staff members serving in the

war, Fry’s had a very disturbing time during the great influenza epidemic of 1918-19. They had to

close the foundry at one point as many of the employees were taken very ill, including one foundry

man who died. The heavy snow at that time didn’t make life any easier.

Publicity map showing location of Fry’s premises in Holland Street

CHAPTER 6

After the First World War

Progress so far had been the result of hard work, with little manufacturing experience except that

of foundry manager Roger Bowbrick, which was somewhat limited, and of course A H Mundey.

Mr Mundey was still employed at Woolwich Arsenal but joined Fry’s Metal Foundry full time after the

First World War. Now there was a surge in trade, better opportunities for men returning from the war

and, as Fry’s was growing, each new member of Fry’s Metal Foundry found a job awaiting him and

he was not taking someone else’s place. Mundey, John Cartland, A W Howe and others were giving a

series of lectures on metallurgy at the London School of Printing and elsewhere. Parties of students

from colleges and schools who visited the works were taken on conducted tours around the foundry

and given lectures. There was tremendous activity – even excitement for the future ahead!

Mr Mundey was without question a good teacher and was able to teach the printing trade through

Fry’s salesmen how best to use printing metals. Mr Mundey delivered a lecture in 1923 to the printers

of Dundee on the subject of metal in the newspaper office. Characters in a romance woven out of

this apparently unpromising material were Tubal-Cain, the first metallurgist, or artificer, on record,

who was chronicled in the book of Genesis as a worker in brass and iron, and a biblical beauty who

pencilled her eyebrows with antimony sulphide. The first type, according to Mr Mundey, was carved

out of birchwood twigs about 600 years ago. Schoolmasters in England had found another use for

the birch twigs, and so the alchemists had to scout around for a substitute and something better and

so they came to lead. Obviously one of the first physical properties of a metal that an alchemist who

was assisting a printer had to make sure about was its ready fusibility. He cast lead into a mould and

got a type easily bent and easily distorted, then looked around to find something to harden it. There

were several other metals known in those days, including antimony and tin. He must have added tin

first and found he had made an alloy. Then he added antimony and found the result was hard, and

thus metal type was instituted. Lead was already known to the ancients, for if we looked at our Bibles,

we would find in Numbers that some of the spoils of the Midianites consisted of lead. Tin was also

known before history recorded it. The British Isles were the great source of tin to the ancients, and the

Phoenicians were said to have come from the Mediterranean in their high-prowed boats to get British

tin from the Scilly Isles and Cornwall.

Fry’s employed printers as travellers who could talk to the customers in their own language, and Mr

Mundey taught these men enough to help the printer to use his metal more efficiently and to a higher

standard. Another feature of the business was what they called ‘reviving metals’ which enabled the

printer to bring back into condition any metals that had ceased to work as they should. These reviving

metals were sold in sticks of about 3lbs each in weight and were distinguished by different brand

names. For Linotype there was a reviver called Frilo, for Monotype, Fromo and for the Typograph

there was Frypo.

Much of the strong competition in the early days came from the likes of T G & J Jubb Ltd of Leeds,

J Holland & Co. Old Kent Road, M Harrison & Sons, Old Kent Road, Hallett & Son, Rotherhithe,

Morris Ashby Ltd (contract with the Monotype Corporation), Wilson & Jubb Ltd, Leeds, Lavin

& Webb (contract with the Linotype Co.), Cookson & Co. Newcastle, manufacturers of ‘C’ brand

antimony, Capper Pass & Sons Ltd, Bristol, Locke, Lancaster & Co. Ltd, Millwall, A Roddick etc. Apart

from the likes of A Roddick, who was drinking heavily, they were mainly scrap metal merchants who

tried to do a bit of type metal business. Jubb’s in Leeds were handicapped by their distance from the

south, and Cookson’s always had only the local trade on the north-east coast. As John Fry said: ‘We

did the job pretty well as far as quality and delivery was concerned, but it was thought that the biggest

factor was the Fryotype service.’

Fry’s Metals faced a turbulent political outlook which was by no means clear, but what they had was

plenty of faith, ideas, ideals and pent-up energy. With the arrival and growth of the car industry, the

manufacture of accumulator batteries was increasing rapidly, and with it the use of antimonial lead.

This all helped in widening the field open to Fry’s, including the by-products, such as the oxides of

these metals (or dross, as it was called in the industry). The correct treatment of this material was little

understood, and quantities were increasing rapidly. Here was an opportunity and John Fry always

knew it.

After the Great War, the activities of the company were broadened to include the manufacture of

anti-friction bearing metals, solders and fluxes, and an entry was made into the field of diecasting. In

the early days the diecasting industry was producing mainly pram hub caps and gramophone sound

boxes, in the then poor-quality zinc alloy. At the 1924 Wembley Exhibition Fry’s had a modest exhibit

with a showcase of diecastings, with small mascots distributed from an Oriental stand that had been

arranged in the diecasting department for a London customer.

A new foundry in Charlton, south of Woolwich, was opened which was rather run down in respect of

the interior. It had previously been used as an iron foundry, and most of the roof was missing, having

been blown off by the big explosion across the river at Silvertown, East London, in 1917. There was

no running water, only a well and a Cupola furnace that had been used for iron, with no water jacket,

but they had a new gas engine installed to power the fans. Dross was sent with one man from Holland

Street, and, with an old chap who had worked at this particular place before, Roger Bowbrick started

up the furnace. It got going alright but after a few hours came trouble. At first, he could not keep the

tuyeres clear of slag and the bearing ran hot, and to cap it all, the furnace started to fume badly. They

soon had people from the neighbouring houses on their case and, after many threats, they demanded

that the furnace was shut down. Roger Bowbrick had to open the bottom valve and let the metal and

slag run on to the earth floor and they were kept busy all night clearing up the mess. A little time

afterwards, they collected their tools, dross, metal, etc. and returned to Holland Street, and that was

the finish of the Charlton foundry.

Back in Holland Street they were still very busy, as John Fry had purchased a site at No. 42 Holland

Street that had been used by a firm of van builders and he was having a new foundry and offices built

there. In 1919 the new block was completed and officially opened by Mrs Fry. It was a great step

forward and for the first time there was a laboratory. The offices were set out for all the staff, with the

exception of the cashier’s department, which stayed at No. 25. The foundry was very well equipped

and had four two-ton pots, two five-ton, one one-ton and one ten-hundredweight (half-ton) solder pot

and a large gas tilter. Fry’s had expanded a lot since 1914 and did a lot of refining for customers at their

own works. At the Daily Telegraph they had a two-ton pot, and two Fry’s men went there twice a week

to clean and ingot their Linotype metal for them, which continued for several years until the Daily

Telegraph did it themselves. Fry’s were now supplying metal to several London newspapers including

the very first order from the Daily Mail. New moulds were cast to hold 56lb [half-cwt], as that was

what their rivals Jubb’s were using.

The making of batches and the

methods of removing impurities

such as zinc, copper and arsenic had

been greatly improved and metals

could now be ‘mixed together’ in

any proportions. Many of them

could also be separated, chiefly by

means of heat control. Gradually

Fry’s were becoming well known for

their manufacture of solders, which

had increased in the capable hands

of C W Hart and his colleagues in

the laboratory and works, along with

Holland Street laboratory c.1919

their growing array of salesman. Large Russian orders for tin-rich alloys were received and financed

by the bank, which were very welcome. In due course further development and introduction of other

alloys belonging to the same metallurgical group, tin, antimony, lead and copper, were made, e.g.

antifriction bearing metals, and antimonial lead, too, was steadily increasing in output.

A little while after completing a large and difficult Russian order, there was very serious trouble at No.

27 Holland Street. They were trying to make the last lot, which held high tin, copper etc., from the

liquating furnace into some usable form. The metal was heated to a high temperature in a two-ton

pot and aluminium was stirred into it. The resulting dross was dried using zinc chloride and removed

before the remaining metal was poured. This was a very hot and nasty job and each evening Roger

Bowbrick took towels, etc., to the men to keep them happy, and was glad when the whole parcel had

been treated. There now remained the villain of the piece, namely the dross. This was in a heap and

in bins in the foundry ready for bagging and there were four men on night shift work to complete the

job. On the first night (Monday) they had to stop, as there was a storm and the men were working

under a glass roof, which leaked rather badly, and they sat around on the bags they had already filled.

They thought everything was OK, but among the four men on the job was one who had started that

evening and, during the following day, news reached Roger Bowbrick that the new chap would not

be coming in that evening, as he had been taken ill and had called in a doctor. Then he heard that

Driscoll, another company employee, was also bad, and his wife had taken him to St Thomas’s Hospital

where he had been admitted. This caused quite an upset and the next news was that the new man had

died on his way to Guy’s Hospital (Wednesday) and that Driscoll in St Thomas’s was very ill, and the