Bulletin 192

December 2014 – Bulletin 192

Some Thoughts on Mitcham and the Great War – Tony Scott

Merton’s Medieval Rebels – Peter Hopkins

More about Lonely Lonesome and ‘Blake’s Follies’ – John W Brown

and much more

PRESIDENT:

VICE PRESIDENT: Eric Montague

CHAIR: Keith Penny

BULLETIN No. 192 DECEMBER 2014

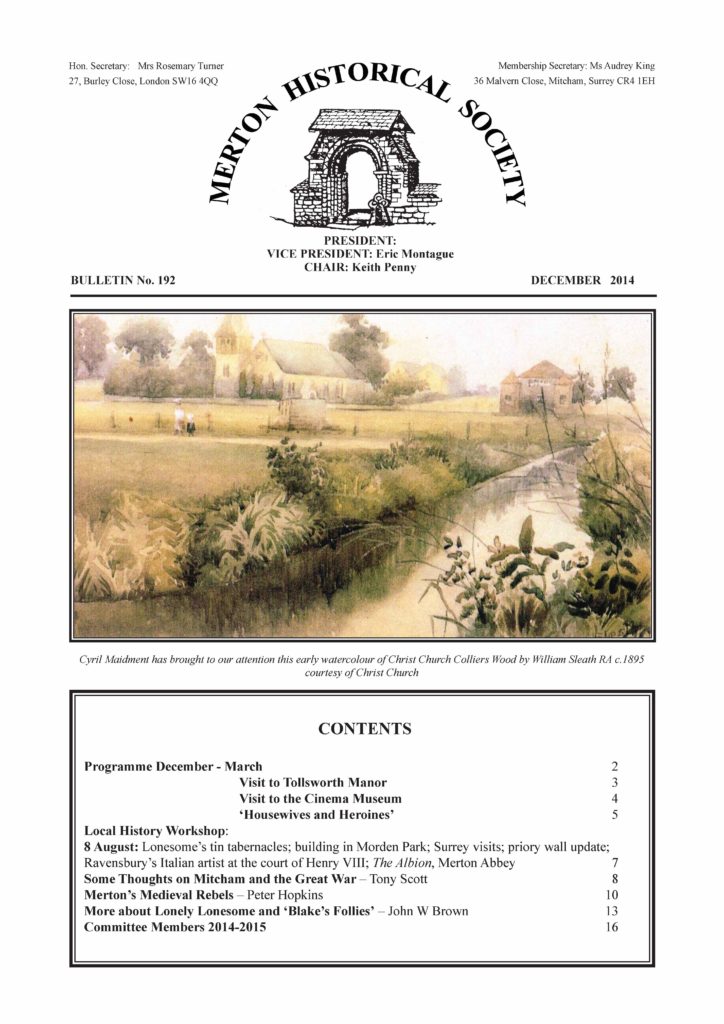

Cyril Maidment has brought to our attention this early watercolour of Christ Church Colliers Wood by William Sleath RA c.1895

courtesy of Christ Church

CONTENTS

Programme December – March 2

Visit to Tollsworth Manor 3

Visit to the Cinema Museum 4

‘Housewives and Heroines’ 5

Local History Workshop:

8 August: Lonesome’s tin tabernacles; building in Morden Park; Surrey visits; priory wall update;

Ravensbury’s Italian artist at the court of Henry VIII; The Albion, Merton Abbey 7

Some Thoughts on Mitcham and the Great War – Tony Scott 8

Merton’s Medieval Rebels – Peter Hopkins 10

More about Lonely Lonesome and ‘Blake’s Follies’ – John W Brown 13

Committee Members 2014-2015 16

PROGRAMME DECEMBER 2014 – MARCH 2015

Saturday 13 December 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Traps, Tradition and Transformations: the curious history of Pantomime’

Illustrated talk by Dr Chris Abbott, researcher of performing arts (puppets, circus etc)

Saturday 10 January 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Recent Researches’

Short talks by several MHS members

Saturday 14 February 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Seven Streets, Two Markets and a Wedding’

Ten archive films for discussion, with Ben Benson, The Touring Local Cinema

Thursday 26 February 12 noon Taste Restaurant, London Road, Morden

Annual Lunch – booking form enclosed

Saturday 14 March 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Past and Present: How Merton, Morden and Mitcham have changed’

Presentation by David Roe, Keith Penny and Mick Taylor of the MHS Photographic Project

Visitors are welcome to attend our talks. Entry £2.

Christ Church Hall is next to the church, in Christchurch Road, 250m from Colliers Wood

Underground station. Limited parking at the hall, but plenty in nearby streets or at the Tandem

Centre, 200m south. Buses 152, 200 and 470 pass the door.

PROGRAMME DECEMBER 2014 – MARCH 2015

Saturday 13 December 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Traps, Tradition and Transformations: the curious history of Pantomime’

Illustrated talk by Dr Chris Abbott, researcher of performing arts (puppets, circus etc)

Saturday 10 January 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Recent Researches’

Short talks by several MHS members

Saturday 14 February 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Seven Streets, Two Markets and a Wedding’

Ten archive films for discussion, with Ben Benson, The Touring Local Cinema

Thursday 26 February 12 noon Taste Restaurant, London Road, Morden

Annual Lunch – booking form enclosed

Saturday 14 March 2.30pm Christ Church Hall, Colliers Wood

‘Past and Present: How Merton, Morden and Mitcham have changed’

Presentation by David Roe, Keith Penny and Mick Taylor of the MHS Photographic Project

Visitors are welcome to attend our talks. Entry £2.

Christ Church Hall is next to the church, in Christchurch Road, 250m from Colliers Wood

Underground station. Limited parking at the hall, but plenty in nearby streets or at the Tandem

Centre, 200m south. Buses 152, 200 and 470 pass the door.

VISCOUNTESS HANWORTH

We are saddened to learn that the distinguished archaeologist Lady (Rosamond) Hanworth died recently. For a

number of years she was President of this Society. An obituary will appear in our next issue.

WILLIAM JOHN (‘BILL’) RUDD

We have learnt with sadness of the death in hospital on 30 October of Bill Rudd, a stalwart of our Society, and

one of its vice-presidents. The funeral took place on 13 November, and a number of MHS members were able

to attend. There will be an obituary in the next issue.

FROM THE EDITOR

This is the 73rd Bulletin I have edited. And it will be the last. The editor’s chair, I am happy to say, is passing

to David Haunton, who will do an excellent job.

I am immensely grateful to all my contributors – volunteers or conscripts. Such a publication is only as good

as its contents, and it has been a joy to receive the range and high quality of material offered. Thank you all.

Special gratitude is owed to Peter Hopkins. The tiny legend Printed by Peter Hopkins at the foot of page 16 does not

do justice to the skill and tact with which he moulds an unwieldy pile of text and pictures into a coherent and

elegant publication. Peter deserves the warmest praise from the Bulletin’s readers.

Judith Goodman

WHERE ARE THEY NOW ?

We would like to contact the authors (or representatives) of three of our Local History Notes. If you know the

whereabouts of Michael Read (LHN 16 Growing up in Mitcham(1939-1963)), Pamela Starling (LHN 23 A

Mitcham Childhood Remembered 1926-45) or Kathleen Watts (LHN 25 A Child’s Eye View of Mitcham) could

you kindly inform Peter Hopkins or the Editor.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 2

VISIT TO TOLLSWORTH MANOR

On a brilliant sunny day we were welcomed to Tollsworth Manor, one of the granges of Merton priory, by Carol

and Gordon Gillett, the current owners of this historic house, situated in the little village of Chaldon, Surrey.

Before taking us on a tour of the house and gardens, Gordon gave us an illustrated talk on their history, the

various owners and the odd things found during restoration. The chimney yielded a circular stone with a dial

scratched on its surface (a sundial ?) of c.1650, one child’s shoe of similar date and a heavy work shoe of

c.1660. A witch’s bottle of c.1670 was found in a wall, its odd contents originally sprinkled with urine, while

a woman’s single day overshoe of c.1750 was found in the roof. (Gordon occasionally asked us questions of

history, which luckily we could mostly answer.)

Merton priory was already a landowner here by 1201/2 when

one William Hansard granted it ‘certain lands in Tullesworth

lying next to the grange of the prior’. We do not know when the

original house was built: it would have been a simple timber-

framed open hall house, to which a two-bay solar (1 on the

plan) containing private rooms was added in 1326-58 (dated

by dendrochronology). It seems that the original hall was then

taken down, and replaced by the existing hall (2-2) in 1433-36

(another dendro-date), giving the most unusual situation of a

solar being older than its hall.

In 1542, after the Dissolution, the property was leased to Richard

Aynescombe, but ownership passed to Sir William Roche

and others in 1544 [together with the priory’s Spital estate in

Morden].The ‘dairy’ (3), of uncertain original use, was added

c.1550; it is unclear whether the staircase (1/3) was installed at

this date, or earlier, with the solar. However, it is probable that

the solar was extended by a third bay (4) by 1604 (dated by an

inscribed stone). Shortly after 1607 (another inscribed stone), Gabriel Aynescombe installed the inglenook

fireplace and chimney and clad the outer walls of the original timber-framework in local Merstham stone. These

quarries have two strata, one harder than the other, and it was the softer (cheaper ?) stone that was used at the

grange, and at the nearby church. The Aynescombes were people of considerable wealth – the Surrey Hearth

Tax records nine tenant farmers in 1664.

The 18th-century Window Tax resulted in the bricking up of two windows in the loft, which was apparently

used as living space. However, the ‘bakehouse’ extension (5) dates from the early 18th century and features an

enormous domed baking oven, with an internal diameter of perhaps four feet (1.3m). The Jolliffe family (Lord

Hylton) bought the estate in 1788, and it underwent various vicissitudes, mostly a tale of damage and neglect.

In the First World War the farm was being run entirely by women, but in 1917 Lord Hylton evicted Mrs White,

the tenant, when her stock included 70 head of cattle and 11 shire-horses. Eventually, in 1936, the house, but

not the surrounding farmland, was sold to the Youth Hostels Association, in a derelict state. The ground plan

was eventually completed by the YHA (6, see

PS. overleaf).

The Gilletts bought the house in 1983; the

enormous garden, which was a combination of

building-rubble tip and neglected forest when

they moved in, is now beautifully laid out with

lawns and borders. There is enough room for a

paddock, housing an amiable elderly pony, and a

duck-pond. Because of foxes, the ducks are only

allowed onto the pond under supervision (often

supplied by the dogs of the household), but from

which they are summoned home by Carol with

sharp handclaps – and they come!

We were richly entertained to tea and lots of home-made cakes, while one of our number, fresh from marshalling

at the 24-hour races at Le Mans, was delighted to recognise, in a photo on the wall, his younger self on the

‘Jaguar pits balcony’ at Le Mans back in 1953! We thanked our hosts for an enormously enjoyable afternoon,

particularly so on learning that our visit fees benefit their local charity, a hospice.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 3

PS. In his forthcoming book, Abbey Roads, Bill Rudd recalled that the YHA relied on volunteers in order to

reduce running costs. The Wimbledon Group he belonged to, together with two skilled members of the Kingston

Group, were largely responsible for the building of an extension to the rear of the Chaldon hostel, the partly

medieval Tollsworth Manor. It was in 1950 that Bill had been one of the members of ‘a long run of weekend

working parties’ at Chaldon. David Haunton

Plan and photo reproduced from Janette Henderson’s new book In Search of Merton Priory’s Granges

VISIT TO THE CINEMA MUSEUM 19 September 2014

Kennington has many corners of interest to the

curious wanderer, and The Cinema Museum

turned out to be one of those museums whose

buildings, as well as the contents, deserve

attention. It occupies the Master’s House of

the Lambeth Workhouse, a vaguely Moorish

building begun in 1871, which visitors approach

between two contemporary lodges, one each for

the day and night porters. The buildings were

erected after an outcry following the exposure

by a journalist, James Greenwood, of the

hideous conditions in the previous workhouse,

an outcry that also led to the suicide in 1877 of

the sometime Master. Among the 800 or more

inmates in 1898 were Charlie Chaplin and his

mother and brother, a cinematic connection

with the building’s present use.

The workhouse lasted until 1922, when the buildings were absorbed into the adjacent hospital. After that closed

during the 1970s, the buildings decayed until most were demolished for new housing, although the Master’s

House was retained for offices, which allowed the Cinema Museum to move there 17 years ago.

All this was explained by Ronald, our guide, as we sat in a small cinema with the usual tip-up seats. He introduced

five short documentary films: a remarkably clear and steady silent depiction of the great flood in Paris in 1910;

a wartime Ministry of Information film about the dangers of spreading rumours; an ‘advanced’ advertising

feature from 1935 by the GPO film unit, produced by painting coloured shapes on the celluloid of the film;

The Elephant Will Never Forget, an elegiac record of the last days in 1952 of London’s double-deck trams (its

director made it against the orders of his superior and was duly dismissed); a Rank colour film about London

coffee bars in the 1960s. All, apart from the GPO film, recorded eras distant in culture, if not so much in time.

Notable in the films was the near-universal smoking of cigarettes, and this practice related to one of the exhibits

seen during Ronald’s tour. ‘Florodol’, a fragrance both disinfectant and antiseptic, was sprayed inside cinemas

to combat the smell of smoke and odours from cinemagoers who did not have the ready access to baths or

showers that we now enjoy. It also addressed concerns about public health. The white screen of the cinema

needed regular cleaning and repainting, because of the yellowing effect of nicotine.

Ronald explained the cut-in system of showing films that ran as a continuous programme, apart from breaks

for the purchase of refreshments, so that people might well arrive during the middle of one film, watch the

second one and then catch up with the part of the first film that they had missed. Usherettes (female, because

they were cheaper to hire), looked out for vacant seats, and the cinema advertised outside if only single ones

were available, so that those who wanted to sit as a couple would know to wait till later.

The tour took us through a mixture of studio photographs, equipment (lots of projectors), uniforms and items

of cinema décor, much of which came from Ronald’s native Aberdeen, rescued by him from a store in which

the contents of ten closed cinemas awaited disposal. Afterwards we took tea in the cavernous first-floor former

chapel. Ronald described the museum as an eccentric sort of place, a judgement it would be hard to contest,

but it certainly does take the visitor back into the days of ‘going to the pictures’.

Keith Penny

The Cinema Museum, The Master’s House, 2 Dugard Way (off Renfrew Road), London SW11 4TH.

Website: www.cinemamuseum.org.uk.

photograph: Judith Goodman

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 4

‘HOUSEWIVES AND HEROINES: WOMEN OF IMPORTANCE IN MERTON’

On 11 October a large audience was treated to a virtuoso account by Sarah Gould, Merton’s Heritage Officer,

of women from many walks in life who have had connections with our area.

She began with royals. Eleanor of Provence (c.1225-1291), consort to Henry

III, stayed at Merton priory, with her husband in 1236. Catherine Parr (15121548),

sixth wife of Henry VIII, in 1544 was granted the manor of Wimbledon,

and is thought to have visited in the following year. Elizabeth I (right) visited

Mitcham several times in the 1590s, and her household treasurer Gregory

Lovell lived at Merton Abbey. Queen Henrietta Maria, wife to Charles I, for

11 years from 1638 owned Wimbledon manor house. Queen Victoria launched

the first competition of the National Rifle Association on Wimbledon Common

in 1868. Her daughter-in-law Queen Alexandra supported local charities,

including Queen Alexandra’s Court, for widows and orphans of servicemen.

Wimbledon’s Alexandra pub, and Road are named after her. Queen Mary, with George V, visited the area during

the First World War, and she also dropped into Pascall’s sweet factory in Mitcham later on.

Some notable women followed. Lively and sharp-tongued Sarah Churchill (1660-1744), Duchess of

Marlborough and chatelaine of Blenheim Palace, in 1723 bought the manor of Wimbledon and built a new

house, which passed to the Spencers on her death. Beautiful and clever Lady Georgiana Spencer (17671806),

born in Wimbledon Park House, loved parties, gambling and politics, but later succumbed to debt and

disease. Such was her fame that her death in her Piccadilly house drew huge crowds. Vivacious heiress Sophia

Johnstone (the fortune came from pins) married a handsome Sicilian, who became Duke of Cannizzaro. In

1817 the couple leased Warren House, Wimbledon, as their country retreat, and entertained lavishly there.

Sophia supported musicians and collected important manuscript and printed music. Her name survives in that

of Cannizaro (dropping one ‘z’) Park.

Lady (Emma) Hamilton (?1765-1815), born Emy Lyon, the daughter of a Cheshire blacksmith, was able to

use her extraordinary beauty to rise in the world. Mistress to Sir Harry Featherstonehaugh of Uppark, and then

to Charles Greville, a son of the Earl of Warwick, in 1784 she was passed by the latter to his uncle Sir William

Hamilton, our envoy in Naples. They married seven years later, and Emma’s talents for singing and languages,

her good humour, and her energy, enabled her to grace the role of diplomat’s wife. Later her liaison with Nelson,

and the ménage à trois with Hamilton, formed one of the scandals of the age. Merton Place (long demolished)

was their retreat from prying eyes.

By contrast, a pair of working women. ‘Widow Bignall’, aged 88, was photographed in Mitcham c.1894 by Tom

Francis. She supported herself by making baskets from osiers (young willow shoots). And Nelly Sparrowhawk,

of Romany descent, was well-known in Mitcham, hawking lavender in the local streets.

Some stars of stage and screen: Florence Gough, in Wimbledon c.1913, was a Tiller Girl. This famous troupe

featured up to 32 dancers, all the same height and weight, doing tap and high-kicking routines. Polish-born

Rula Lenska, of Rock Follies, Minder and West End roles, was in Gladstone Road, Wimbledon 1979-83. Kate

O’Mara, of Triangle and Dynasty fame, lived for a time in Merton Hall Road and Lansdowne Road. Doris

Hare (1905-2000) had a nearly 90-year career in radio, stage and television in everything from Shakespeare

to On The Buses, and was made MBE for wartime services to the Merchant Navy. She lived in Burghley Road

for many years. Sylvia Peters, famous BBC voice from 1947, and later TV presenter, lived for a time at two

Wimbledon addresses. Edinburgh-born (1934) Annette Crosbie has lived in Manor Gardens, Merton Park, for

many years. She made her name as Catherine of Aragon in The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1970) and has had a

busy career since. She is best known now as the long-suffering wife in One Foot in the Grave. She was made

OBE in 1999. Theatre and film actress Jane Baxter (1909-1996) was in Belvedere Road in the 1980s. Barbara

Lott (1920-2002), best known perhaps for Sorry, with Ronnie Corbett, lived in Church Road, Wimbledon.

Much-loved comedy actress June Whitfield OBE (b.1925) has lived in Wimbledon for many years. Kathleen

Harrison (1892-1995) of Here Come the Huggetts fame was in Wimbledon for the last 40 years of her life. Even

Joanna Lumley (b.1946) lived in Wimbledon for a year. Ballet dancer, teacher and choreographer Laetitia

Browne lived in Ridgway Place.

And then there were the literary ‘heroines’. Scottish-born Margaret Oliphant (1828-1897), author of the

Chronicles of Carlingford series and other books, lived near Wimbledon Common at the end of her life. Anne

Thackeray Ritchie (1837-1919), daughter of Vanity Fair author W M Thackeray, was herself a writer and

novelist, and made Wimbledon her home. Georgette Heyer (1902-1974) was best known for her witty and

well-researched Regency novels, but also as a respected crime writer. She was born and raised in Wimbledon.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 5

Ethel Mannin (1900-1984) is perhaps best remembered for Confessions and

Impressions (1930). Children’s author Elizabeth Beresford (1926-2010)

is famous as the creator of The Wombles of Wimbledon Common. Another

children’s writer was Dorothy Sheppard (1917-?), who lived in Denmark

Road. More novelists with local connections include Mollie Chappell

(1914-?), Jean Stubbs (1926-2012), Mavis Cheek, Michelle Paver, ‘chick

lit’ author Madeleine Wickham (b.1969) and Edna O’Brien (b.1930), who

wrote her Country Girls trilogy while living in Cannon Hill Lane, Merton.

An array of charitable souls: Elizabeth Gardiner (d.1719) of Morden left

£300 for the education of poor children of the parish. A hundred years ago

and more, Ethel Crickmay of High Street, Wimbledon, raised funds to

buy and care for a succession of shire horses, all known as ‘Jack the trace

horse’, to help haul loads up the hill to the village. Vera Corner Halligan,

of Grand Drive, Raynes Park, was made MBE in 2002 for her lifetime of

work with the Sea Rangers. Mary Smith MBE of Vineyard Hill Road was

honoured in1966 for her work in housing. Agnes Maynard of Woodside

was a pioneer in the Girl Guide movement before the first World War. Annie

Collin (1852-1957) of Grosvenor Hill founded and ran Friends of the Poor,

which supported a range of charitable projects. Evangelical Charlotte Marryat (mother of the novelist)

raised funds for Wimbledon’s almshouses, and in Mitcham Mary Tate financed the almshouses that are now

known as Mary Tate Cottages. Shopkeeper’s wife Priscilla Pitt (1828-1899) of Mitcham was a Quaker, active

campaigner for pacifism and temperance, and supporter of what became the NSPCC. Keziah Peache (18201899)

of Wimbledon supported many charities and financed housing for poor families ‘of good character’, such

as Bertram Cottages between Hartfield and Gladstone Roads.

In the realm of art: Distinguished artist Angelica Kaufmann (1741-1807) is thought to have painted decorative

schemes at Cannizaro and Lauriston House. Margaret (‘May’) Morris (1862-1938) was William Morris’s

younger daughter and a skilled designer and needlewoman. She was briefly part of the design team at the Morris

works at Merton Abbey. Joyce Bidder and Daisy Borne, notable 20th-century sculptors, shared a Wimbledon

studio. Nancy Kominski (b.1915), familiar as a TV artist (‘Paint Along with Nancy’), lived in Wimbledon, as

does well-known portrait-painter June Mendoza.

Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932) created gardens in Wimbledon and Merton Park.

Courageous campaigner for social and political reform, Josephine Butler (1828-1906), lived in Wimbledon.

Another brave activist – first with the Cyclists’ Touring Club, and then with the Suffragettes, was Rose Lamartine

Yates (1875-1954) of Merton Park. Margaret Roney (1873-1957) was Wimbledon’s only female mayor.

Women MPs have included Conservative Janet Fookes and Angela Rumbold. Siobhain Mcdonagh is the

Labour MP for Mitcham & Morden, having previously been a Merton councillor. The present Home Secretary,

Conservative Theresa May, was also a Merton councillor.

Second World War heroine Violette Szabo (1921-1945), who was awarded a posthumous George Cross, had

worked briefly in a Morden factory, making aircraft switchgear.

And some sportswomen: Mitcham Athletic Club had a great reputation and produced fine athletes. The best

known is probably high-jumper Dorothy Tyler, née Odam, who competed in 38 international events – including

four Olympic Games (1936-1956), in which she won two silver medals. Dorothy died in September 2014. Finally

Sarah spoke about Virginia Wade (b.1945), whose education included time at Wimbledon County School. She

was ranked in the world top ten women tennis players for 13 years, and famously she won Wimbledon in 1977,

the Queen’s Silver Jubilee year.

Sarah was warmly thanked and applauded for this impressive and fascinating account of notable women.

photo of Edna O’Brien

by Van Paliser 1969 for Penguin

‘FIELDS UNSOWN’ EXHIBITION

This thought-provoking little exhibition displays some of the source material for Attic Theatre Company’s

play Fields Unsown, performed in Morden Hall Park in September. It includes some family items kindly

made available by Madeline Healey. If you missed it in the Morden Hall Stable Yard in October, and in

Mitcham Library (home of Attic Theatre) in November, it will be on view at Merton Heritage and Local

Studies Centre in Morden Library throughout January.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 6

LOCAL HISTORY WORKSHOP

Friday 8 August 2014 – six present – Peter Hopkins in the chair

.

Keith Penny had discovered the architect H P Burke Downing (see June 2014, p.7) had married a 25-yearold

lady in 1937, when he was about 70. He lived in Colliers Wood for about 40 years.

Keith had a slight error in his

article on Lonesome (see June

2014, p.9). There were actually

two ‘iron mission huts’, and

the locations were not stated

accurately. The first – the

Streatham Baptist hut, built in

1887, with a match-boarded

interior capable of holding 100

people – was in Leonard Road;

the second one was the Anglican

Good Shepherd Mission Room

off Lilian Road and south of

Marian Road (plot 6726 on the

1910 Valuation map, TNA IR

121/8/3) This was a corrugated

iron rectangle with bellcote, built

in 1906, run by the Church Army

and later financed by Sales of

Work yielding as much as £200

a year. The Army left in the mid

1930s as the parish was reorganised. The site was originally bought from the Gas Mantle Manufacturing

Co. (alias Dura Incandescent Co.), and was sold in 1936 to a Mr Marchant, with a restrictive covenant

forbidding its future use as club or billiards rooms, or for the sale of alcohol. The shape of the plot can still

be distinguished on a Google Earth view of 1985, containing substantial housing.

.

Madeline Healey mentioned that a house was being built where there was previously a sports-related

building in Morden Park. She noted that this land, behind Hillcross Avenue and near the railway, was not

restricted to be only for sports.

.

Sheila Harris has recently visited (on a coach trip) Abinger Church, and the nearby ‘Goddards’, the house

designed by Edwin Lutyens, with gardens by Gertrude Jekyll. This is owned by the Landmark Trust, and

part is open to guided tours on Wednesday afternoons, Easter to October. Sheila thoroughly recommends

visits to both.

.

David Luff reported on the Priory wall (see September 2014, p.10), and two lines of large holes that he has

discovered close to the wall. One line lies north-south, the other at right angles; one example that David

cleared of its filling of car tyres and bricks proved to be 24 inches (0.6m) deep. Dave Saxby could not offer

an explanation. David suggests these are holes for substantial posts and may represent a medieval building

just outside the Priory wall.

.

Peter Hopkins has been pursuing traces of Anthony Toto, an Italian Tudor artist. He held two cottages and

12 acres in Mitcham, and in 1542 was given a 40-year lease of the Manor of Ravensbury in Mitcham and

Morden. Within only four years he succeeded in upsetting many local people to the extent that court cases

were brought. He was a serjeant-painter to Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary, ornamenting royal palaces

(including Hampton Court), temporary banqueting houses (one in Hyde Park), and flags and streamers for

the royal ships. Peter is preparing a long article on this interesting man for future publication.

Peter had accepted on behalf of the Society the gift from Mrs Pat Brown of a clear glass jug from The

Albion pub, surprisingly of 1 litre (1.75 pints) capacity. It is engraved WITH / COMPLIMENTS / FROM /

M.JONES. / “THE ALBION” / MERTON ABBEY S.W. / XMAS. 1923 in rather square-cut letters. If you

can supply any information about the item, the occasion or Mr Jones, please contact the Editor.

David Haunton

Dates of next Workshops: Fridays 19 December, 30 January, 13 March at 2.30pm

At Wandle Industrial Museum. All are welcome.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 7

TONY SCOTT offers

SOME THOUGHTS ON MITCHAM AND THE GREAT WAR

Mitcham has two public war memorials. The obvious one is in Lower Green West very close to the fire station

at the Cricket Green and the other is in Mitcham parish cemetery in Church Road. This latter is the simple, but

very effective ‘Cross of Sacrifice’ memorial, composed of a metal cross inset in a stone cross, on a hexagonal

plinth with a two-tiered base. It is similar to many around the country and overseas and is to a design of Sir

Reginald Blomfield. There are no individual names on the monument and it bears the inscription:

‘This Cross of Sacrifice is one in design

and intention with those which have

been set up in France and Belgium and

other places throughout the world

where the dead of the

Great War are laid to rest.’

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has identified 52 First World War graves scattered through the

cemetery, each having the standard format Portland stone headstone.

The memorial in Lower Green West bears the inscription on the front face:

‘Their name liveth for evermore

To the men of Mitcham who falling, conquered,

in the Great War. 1914-1919.’

There then follows on the front face 123 names in alphabetical order, surname and initials, with no rank,

regiment, decorations or date of death. There are similarly 156 names in each side and 153 on the rear face,

making a total of 588 names. The date range of 1914-1919 is not a mistake, for although the Armistice took

effect on 11 November 1918, by common consent any serviceman who died during 1919 as a result of the war

was considered as one of the war dead.

The memorial was unveiled on 21st November 1920 by Lieutenant General Sir Herbert Edward Watts, KCMG.

In more recent years an additional rectangular stone plaque was fixed to the steps below the front face. This reads

‘and to the memory of the men, women and children who lost their lives in the Second World War. 1939-1945’.

There is a smaller rectangular stone plaque fixed below this, which reads

‘and those killed in other conflicts’.

The War Memorial,

Lower Green West

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 8

I would imagine that virtually all of the names on the memorial were soldiers with perhaps a few from the newly

formed Royal Flying Corps. I would not expect any sailors from Mitcham. Most of the men would initially

have been in the East Surrey Regiment, because ever since the Cardwell reforms of the army in 1871/2 when

numbered Regiments of Foot were combined into County Regiments, ‘local recruitment’ was the army policy.

It was only after the tremendous losses of the Battle of the Somme in July and August 1916 that a serious

drawback to local recruitment was realised. When a regiment ‘went over the top’ and suffered very serious

losses, it was possible that virtually all of the men from a specific village who were of military age were killed

on the same day. Dispersion of soldiers into any regiment that had suffered losses or needed expanding was

the new policy from late-1916.

Returning to the list of the fallen. They were all Mitcham young men, many of whom drank in the pubs that

remain today, probably attended schools that are still there today (at least in name although most have been

re-built) and worked in the fields where subsequently many of our houses have been built.

At least two of the Mitcham men whose names are on the war memorial had locally distinguished parents:

Douglas Walter Drewett, born 1883, died 30th October 1918 aged 35.

He was the second son of James Douglas Drewett JP who lived with his wife Bridget in a large house called

Ravensbury facing the Fair Green near the clocktower. This was demolished to build the Majestic Cinema and

on this site now is the red brick two–storey block on the corner of Majestic Way. J D Drewett was at various

times Chairman of Mitcham Parish Council and Vice-Chairman of Surrey County Council.

Lieut. William Herbert Mostyn Simpson of the East Surrey Regiment, born 1893, died of wounds in Belgium

on 19th December 1914, aged 21.

Herbert Simpson, as he was known, was the eldest son of William Francis Joseph Simpson, the lord of the manor

of Mitcham Canons, and his wife Winifred. They lived in Park Place, Commonside West. Herbert Simpson was

the great grandson of William Simpson who married Emily Cranmer in 1818 and who in due course inherited

the lordship of the manor from the Cranmer family. Herbert Simpson was expected to inherit the lordship of

the manor from his father.

As it was British Government policy until at least after the Second World War not to repatriate the bodies of

those who died in conflict, who were those military personnel who are buried in Mitcham parish cemetery?

The answer may lie in the local military hospital/convalescent wards.

At least one of the male dormitories of the Holborn Union Workhouse in Western Road, Mitcham was used as

a military convalescent home, so also was the Catherine Gladstone Home in Bishopsford Road, just outside the

parish. Locally, but not within Mitcham parish, Edward Gilliat Hatfeild offered Morden Hall to the War Office

in 1915 for use as a military hospital and between 1915 and 1919 nurses looked after wounded soldiers of below

officer rank at Morden Hall. I am not suggesting that only Mitcham men occupied these beds, but there were

similar hospitals/convalescent homes around the country. The 52 gravestones in Mitcham cemetery represent the

men returned injured to the UK, only to die in this country, probably in the immediate Home Counties. Most

would have been Mitcham men but some may well have been men from further afield whose remains, for some

reason, were not returned to their home area. Some must have died from infection following wounds, some

from the long-term effects of gas and some, I am sure, died of influenza which was a great killer at that time.

This little explanation and collection of thoughts may stir some ideas and thoughts in the reader. It may in a

small way bring home the shock, horror and sadness that hit many families in Mitcham, rich and poor, during

those fateful war years when the news of the loss of their son, brother or father was received in the War Office

telegram.

‘BIGGER PICTURE’ PROJECT

The Bigger Picture Project of Film London, in conjunction with Merton Heritage and Local Studies

Centre, is looking for old film or video that was shot in Merton. Home movies are welcome: families

at home, parties in the park, works outings or well-known events. If you think you may have some

home-produced film of potential local interest, or know someone who has, please consider offering

it to the Project: get in touch with Sarah Gould at Morden Library or with any member of the Merton

Historical Society Committee. Film London’s website is www.filmlondon.org.uk/lsa. The Project’s

‘KinoVan’, a travelling cinema-in-a-van, will be showing films outside the Civic Centre at the Lighting

Up Morden event in early December. Keith Penny

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 9

PETER HOPKINS has been uncovering the secrets of

MERTON’S MEDIEVAL REBELS

While checking an entry in the published Calendar of Patent Rolls of Henry VI, I glanced through the index to

see whether there were any other local references. I was surprised to discover several inhabitants of Merton and

Mitcham, and one from Morden, included among a list of 3449 named individuals granted a royal pardon in July

1450 for their involvement in Jack Cade’s rebellion.1

Cade, who also used the pseudonym John Mortimer, was the leader of a contingent of Kentish protesters who

marched on London to petition the king about the corrupt and oppressive activities of the royal advisors and their

agents. Henry was a weak, though stubborn, king who mismanaged affairs at home and abroad. The Hundred

Years War between England and France was coming to an ignominious end, with most of Normandy having

fallen to the French by the spring of 1450. At home there were complaints about high taxation to pay for the

unsuccessful war, especially as poorly-provisioned English soldiers travelling to the Channel ports had become

accustomed to helping themselves to whatever food they could find. This was a period of slow recovery from

further outbreaks of plague and poor harvests, and of collapsing international trade, especially in wool and cloth.

But the main outcry was against the king’s advisors and their agents who abused their powers through the use

of extortion, bribery and oppression.

In January 1450 the House of Commons impeached the king’s most influential advisor, William de la Pole,

duke of Suffolk – and incidentally lord of the manor of Ravensbury by right of his wife. To protect him from his

enemies, the king sentenced the duke to 5 years banishment, but he was intercepted on his voyage to the Low

Countries and killed. His body was washed up on Dover Sands and a rumour spread throughout Kent that the

king intended to blame the whole county for the deed – the community was always held responsible for a murder

if no perpetrator could be identified.

Meanwhile an order went out to muster the local militia forces – the medieval equivalent of the Home Guard – to

resist threatened invasions from France. In every community across Kent men were paraded with their weapons

and encouraged to defend the realm against its enemies. As

one writer puts it, ‘The government had enemies across

the Channel in mind, but the militiamen knew that the

kingdom’s true enemies lay nearer at hand, just across the

Thames’.2

The immediate cause of the rebellion is not known, but in

May 1450 the Kentish rebels began to march on London,

and by early June more than 5000 had assembled at

Blackheath, 12 miles south-east of the capital, having been

joined by supporters from Sussex, Surrey, Essex, and further

afield. Of those who sought pardons, 58% were from Kent,

13% from Sussex, 11% from Surrey and 5% from Essex,

while the origins of 10% were unspecified.

Bedford, 2

Berkshire, 1 Bristol, 2

Cambridge, 2

Cornwall, 2 Derby, 1 Devon, 1 Essex, 170

Essex &

Middx, 6

Hereford, 1

Hertford, 1

Kent, 2007

Kilkenny, 1

Leicester, 2

London, 9

Middlesex, 15

Oxford, 3

Salop, 1

Suffolk, 17 Surrey, 391

Sussex, 438

York, 1

unspecified,

375

by unt B df d

15% were craftsmen and traders – bakers, brewers, butchers, carpenters – but

unspecified,

1361

craftsmen

& traders,

513

husbandmen,

510

yeomen, 442

esquires, 26

constables, 75 other, 51

also merchants, goldsmiths, grocers and mercers, 15% were ‘husbandmen’

– tenant farmers – 13% ‘yeomen’ – small freeholders – and 6% ‘labourers’ –

though unfortunately no description was given for 39%. 4% were identified

as the ‘constables’ of the various hundreds – the administrative subdivisions

of the counties – and it is significant that it was the elected constables of the

hundreds who were responsible for mustering the local militia. 4% were

wives, mostly accompanying their husbands though a few were widows. But

another 4% of those seeking pardons were described as ‘gentlemen’ and three

individuals were knights and 26 ‘esquires’, while 13 were clerks, parsons or

heads of monastic houses.

The king sent heralds to order the protesters to withdraw, but they refused, declaring that they were not rebels

but loyal petitioners seeking redress of their grievances. In response Henry moved his army to within sight of

Blackheath and the protesters, unwilling to fight the king – which would have been treason – dispersed under

cover of darkness. Henry then ordered a contingent of his army to pursue the retreating rebels, but the soldiers

were defeated by the mob and several of the army commanders were killed. The king fled to Kenilworth castle

while the rebels returned to Blackheath, where they were joined by many mutinous soldiers, and then entered

Southwark. On 3 July they crossed London bridge and entered the City, but initial support soon faded after a

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 10

couple of high-profile executions, followed by looting. On Sunday 5 July a battle on London bridge resulted in

many deaths on both sides, but the rebels were ejected.

During a truce on the morning of Monday 6 July the two archbishops and the bishop of Winchester were sent

by the queen to offer a general pardon, which was accepted by the vast majority. The Patent Roll entry for 6

July 1450 begins: ‘General pardon to John Mortymer, at the request of the queen, though he and others in great

number in divers places of the realm and specially in Kent and the places adjacent of their own presumption

gathered together against the statutes of the realm to the contempt of the king’s estate; and if he or any other

wish for letters of pardon, the chancellor shall issue the same severally’. On that day and the next some 3400

individuals received their pardons, and their names are listed on the rolls, with the frequent addition ‘and all others

in the said hundred’ or ‘town’. This total omits sixty who were listed twice – or more – many of them identified

as constables of the hundreds. It seems that at first the constables were sent to receive pardons on behalf of the

members of their communities, but many decided that an individual pardon was preferable to a group pardon.

One oddity is that some of those named as receiving pardons were almost certainly not among the rebels or their

supporters. Some are known to have been agents of the hated government officials. Three heads of monastic

houses are named, with their convents, men and servants – the prior of Lewes, the abbot of Battle and the abbess

of Barking (the latter being Katherine de la Pole, sister of the murdered duke of Suffolk). It has been suggested

that ‘some people may have sought a pardon in case the government tried to remedy some of the rebels’ grievances

by instituting legal proceedings against those they criticised’.3

Of the named Surrey inhabitants who

received pardons 21% were husbandmen,

18% yeomen, 10% labourers, and 25%

unspecified. 2% were constables, 5%

gentlemen and 2% wives. A wide range

of craftsmen and tradesmen make up the

remainder, many of them from Southwark,

who supplied 18% of the total pardoned in

Surrey, though it has been suggested that a

further single group of 339 where location

and occupation is unrecorded, including

114 women, 106 of them listed alongside

their husbands, are likely to have been

‘inhabitants of Greenwich or Southwark

who may have fed and accommodated the

rebels’.4 Charlwood and Streatham each

supplied 7% and Addington 6% – the

same as Merton! Next came Croydon at

5%, Ewell with 4%, and Mitcham and

Wallington each with 3%. So our area

was well represented!

Bansted, 2

Chelsham, 6

Cheyham, 5

Chipsted, 2

Collesdon, 1

Copthorne, 3

Adyngton, 24

Batrichesey, 3

Bedyngton, 6

Bermondesey, 8

Birstowe, 1

Blecchynglye, 2

Charlewode, 26

Crassalton, 8

Croydon, 20

Cullesdon, 3

Dorkyng, 11

Ebbesham, 3

Effyngham, 5

Estpekham, 3 Ewell, 14

Great Bokeham, 3

Hedle, 8

Lambehith, 5

Lambehithemerssh, 3

Letherhede, 6 Little Bokeham, 1

Lyngefeld, 4

Nutfeld, 1

Oxstede, 5

Pecham in Camerwell, 5

Totyng, 1

Lymnesfeld, 3

Merton, 22

Miccham, 13

Moredon, 1 Newynton, 3

Sanderstede, 6

Streteham, 26

Suthwerk, 71

Sutton, 3

Totynggravenyng, 10

Walyngton, 13

Warlyngham, 6

Wodemersthorne, 4 Wolkestede, 4

Wotton, 8

Two Mitcham men, Richard Stone (a carpenter) and John Bele (a husbandman), were numbers 1096 and 1097 to

receive pardons for themselves and ‘all others of that town’, probably indicating that they were the headboroughs

or chief tithingmen of Mitcham (or of one of its manors), but Stone and 7 others from Mitcham and 1 from Morden

later received pardons with the two constables of Wallington hundred, both yeomen, one from Croydon the other

from Coulsdon (2528-2538). The Mitcham group were: Robert Chertesey, draper, and Alice his wife; William

Coventre, yeoman; Cornelius John, servant; William Chilton, cordwainer [shoemaker]; William Heryngman,

husbandman; and Richard Dyssher, husbandman; while the lone representative from Morden was John Sauger,

described as a husbandman but in fact the lessee or farmer of Westminster abbey’s demesne lands in Morden,

and the abbey’s rent-collector here.

Meanwhile, 8 Merton men and 3 from Mitcham came as a group – perhaps the Mitcham men (Simon Yong,

yeoman; John Shipman, yeoman; Geoffrey Yong, smith) were from Merton priory’s Mitcham manor of Biggin.

All but one of the Merton group were yeomen – William Baynard, William Longlond, Richard Foxley, John

Salyng, John Malard, William atte Wode, William Goly – while John Bachelor was a husbandman (1213-1223).

Finally, another group from Merton came (2550-2562), led by a gentleman, Thomas Codyngton of Merton, who

was lord of the manor of Cuddington (90 years later to be taken by Henry VIII for the site of Nonsuch Palace).

His companions were John Philpot, John Ismonger, John Lyghtfoot, William Stonyng, Robert Techesey,

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 11

Thomas Carleton, John Semer, John Palmer, Ralph Carleton, John Carleton, together with John Salyng and John

Bacheler, who had been in the previous group and can therefore probably be identified as the chief tithingmen

of Merton. The Salyng family held freehold and copyhold properties in Merton later in the 15th century, and a

William Salyng became prior of Merton in 1502, while another John Salyng was one of the last canons. Many

of these names are familiar from the Merton court rolls which survive from the 1480s, while Malard, atte Wode,

Lyghtfoot, Dyssher and Bele also held copyhold properties in Morden.

Perhaps the most intriguing Merton inhabitant to obtain a pardon was

another gentleman, William Lovelace, who also had substantial property

interests in Morden and in Mitcham and adjoining parishes. He was a

citizen of London, and originated from Bethersden in Kent, where his

memorial brass of 1459 can still be seen. He seems to have been the

eldest of three brothers, each of whom obtained their pardon, Richard

(no.189), William (571) and the youngest, Robert (2140). Among the

famous Paston Letters is one describing the events of 1450 from a servant

of the Pastons’patron, Sir John Fastolf, one of the hated officials.5 Fastolf

sent his servant to Blackheath to obtain a copy of the petition that Cade

had produced, but the man was recognised and nearly killed, before

finding support from leading rebels, one of whom later married a Paston.

He was taken to the rebel headquarters at the White Hart in Southwark,

where Cade commanded a certain Lovelace to relieve the prisoner of his

possessions. It seems likely that this leading rebel was one of the three

Lovelace brothers, probably the youngest, though some have suggested it

was Richard’s son, who during the Wars of the Roses was to acquire ‘the

reputation of being the most expert in warfare in England’ but, as he was

only aged about 10 in 1450, that seems improbable!6 Robert and Richard were involved in a land purchase in

Bethersden as early as 1414 while William was granting land there in 1417, so none of them were young men

in 1450.7 In 1433 Richard, described as a citizen and mercer of London, and William, described as ‘of Merton,

gentleman’, were appointed executors to Beatrice Hayton of Merton, widow of Thomas Hayton who held the

sub-manor of Batailles in Ewell, and William was involved in litigation over her sheep, and also over his own

wool exports, into the early 1440s.8

So, as well as being a hotbed of social and political unrest, mid-15th-century Merton seems to have been a

magnet for wealthy individuals. William Lovelace died without issue, and his Kent estates passed to his brother

Richard, but he left enough personal wealth to fund a chantry chapel for himself and his parents at Bethersden.9

Beatrice Hayton, who was buried with her husband at Merton priory, left legacies totalling in excess of £35,

her husband’s estates having already passed to their daughter. Thomas Codyngton, who is described in Morden

records as a goldsmith, may have had financial problems as in 1430 he was leasing to a London grocer a

messuage and 100 acres arable in Cuddington, perhaps his manor house and demesne lands, plus pasture rights

in Sparrowfeld common for 60 cattle and horses plus 100 sheep, for the annual payment of a pair of spurs

worth a mere 6 shillings, which might indicate that he was indebted to the grocer.10 And in 1452 and 1454 we

find mention of a ‘William Banyerd alias Banyard of Merton gentilman’.11 But where did they all live? Church

House was the only substantial freehold property, and the copyhold properties seem to have been quite small,

but there were leasehold houses near the priory gate at the time the priory was dissolved,12 and I suppose it is

possible that West Barnes was already a leasehold estate before it is noted as such in the 16th century. Perhaps

one day another chance discovery will provide further answers!

1 Calendar of Patent Rolls Henry VI 5 (1909) pp.338-374, accessed September 2014 from https://familysearch.org. My Excel spreadsheet of all entries

is available at http://www.mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk/index.php?cat=morden&sec=!rebels

2 Montgomery Bohna ‘Armed Force and Civic Legitimacy in Jack Cade’s Revolt 1450’ in The English Historical Review 118.477 (2003) p.574;

Bertram Wolffe Henry VI (1981) p.233

3 Mavis Mate ‘The Economic and Social Roots of Medieval Popular Rebellion: Sussex in 1450-1451’ in The Economic History Review n.s.45.4 (1992)

pp.668, 670; R A Griffiths The Reign of Henry VI: The exercise of royal authority 1422-1466 (1981) pp.620-622

4 I M W Harvey Jack Cade’s Rebellion of 1450 (1991) p.196

5 James Gairdner The Paston Letters 1422-1509AD I (1910) letter 99 pp.131-5

6 Montgomery Bohna ‘Armed Force and Civic Legitimacy in Jack Cade’s Revolt 1450’ in The English Historical Review 118.477 (2003) p.579 citing

Waurin Croniques (Rolls Series 1891) 5 pp.327, 334; J Hall Pleasants ‘The Lovelace Family and Its Connections (I)’ in The Virginia Magazine of

History and Biography 27.3/4 (1919) p.398

7 A J Pearman ‘The Kentish Family of Lovelace’ in Archaeologia Cantiana X (1876) pp.185-7

8 The National Archives PROB 11/3/347; C 1/11/125; C 1/43/50; Calendar of Patent Rolls Henry VI 4 (1908) p.18

9 A J Pearman ‘The Kentish Family of Lovelace’ in Archaeologia Cantiana X (1876) pp.187-8

10 Westminster Abbey Muniment Room 27374, 27376 and 27377; Thomas Madox Formulare Anglicanum (1702) 485 pp.285-6

11 Calendar of Patent Rolls Henry VI 5 (1909) p.491; 6 (1901) p.133

12 The National Archives LR 2/190

William Lovelace’s brass at Bethersden.

Photo downloaded from www.geograph.org.

uk/photo/2943848, Image Copyright Julian P

Guffogg, licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic Licence.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 12

Following Keith Penny’s contribution about Lonesome in our June issue JOHN W BROWN relates

MORE ABOUT LONELY LONESOME AND BLAKE’S FOLLIES

I read Keith Penny’s fascinating article ‘Down Lonesome

Way’ in the June Bulletin, as ‘Blake’s Follies’ have always

fascinated me, and I have researched their history.

These dilapidated and deserted old houses were well known

to my father, who, as a young boy, played among the ruins

with his brothers and friends, despite the widespread local

assertion that they were haunted!

The name ‘Lonesome’ aptly described the then isolation of the

area. This outpost of Mitcham parish, abutting a distant and

oft forgotten corner of Streatham, was a notorious haunt of

Gypsies who, prior to the building of the houses in Leonard,

Lilian and Marian Roads, were the chief residents of the area.

My maternal grandfather William Charles

Brown (aka William Charles Young) used to visit

Lonesome to enjoy a pipe and a drink with the

Gypsies, and would treat any of their horses and

ponies that were sick. He was raised in Upham,

Hampshire, and had a way with horses. I remember

discovering reference to him as being an ‘ostler’,

and wondering what mysterious trade that could

be, only to discover that it meant a stableman.

Despite his frequent socialising with the Gypsies

at Lonesome he would always tell his children

never to go there, and never to play with the Gypsy

children.

Muggings and robberies were not the only dangers the lonely traveller

faced in this remote and chiefly uninhabited area. That part of Greyhound

Lane leading westward across the fields from Streatham Common

station was in poor repair and pitted with potholes, and accidents were

commonplace, particularly to horse and cart.

As referred to by Keith, the remoteness of the spot had encouraged it to

be selected as the location for the chemical works which had been built

c.1853 on the site of Lonesome Farm. The works are thought to have been

built by Thomas Forster, following the sale of his Streatham factory to P

B Cow. It probably started life as a rubber works. Forster seems to have

operated the business in partnership with a Mr Gregory, as directories

list the works as Forster & Gregory Chemical Works. Forster lived in

Streatham and is buried in the crypt of St Leonard’s church.

By all accounts the process undertaken at his works was a dirty one, and

contemporary reports refer to a foul smell coming from the plant. This

would have mingled nicely with the fragrance emanating from the local

slaughterhouse, and both would have helped to ensure the continued

loneliness of Lonesome!

The heavy clay soil forming the land thereabouts was always boggy, especially in wet weather, and was overgrown

with weeds and brambles. Occasionally tramps and Gypsies would camp in the dilapidated old houses, seeking

shelter from the ravages of the winter weather.

As Keith mentions, in the early 1900s a number of journalists ‘discovered’ Lonesome and wrote about the area,

with their articles appearing from time to time in the national press. In 1906 a reporter from the Daily Chronicle

ventured into this wildness, and his report on his experiences in trying to find this elusive spot was published in

the issue of 6 October, and is reproduced below. It paints a wonderful picture of the area at that time.He begins

his journey at Mitcham Junction station and the ‘Beehive’ mentioned in the text is the Mitcham pub of that

name and not the old Beehive coffee tavern by the entrance to Sainsbury’s supermarket at Streatham Common.

Longthornton Road Blakes Follies

Morning Leader 22 July 1901

Lonesome Lane-Streatham Vale 1912 by R Paton

Lonesome Lane-Streatham Vale 1910

by R Paton

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 13

Longthornton Road Blakes Follies

Morning Leader 22 July 1901

The Daily Chronicle 6 October 1906

DESERTED VILLAGE

Lonesome in Name and in Character

GEOGRAPHICAL PUZZLE

“Lonesome? Lonesome? Never heard of it sir.” And the ancient rustic rubbed his chin thoughtfully, and gazed

at me out of suspicious eyes. I had been dropped by a leisurely train (writes a correspondent) on the edge of an

English common, and I was in search the village with the fascinating name, which my rustic friend had never

heard of. Before the search was over I had overcome my surprise at his ignorance. Neither gazetteer, railway

time table, Post Office guide nor map had yielded the secret of Lonesome’s position in spite of diligent search.

Even in the immediate neighbourhood, I was sent off on many false trails and headed backwards and forwards

by turnings to the right and to the left, and I had lost all sense of locality. Yet Lonesome was there all the time,

huddled and hidden away in a beautiful bit of English countryside, with green fields about it and a sheltering

wood and its own way of living from one year to the other. It was an intelligent carrier who first put me on the

right trail.

“See that white board?” he said, pointing with his whip straight along the dusty road. “Well, go on till you reach

that, cross the railway bridge, turn to the left past the Beehive inn and then follow the footpath.”

The directions were precise, if somewhat lengthy, and I proceeded to follow them to the best of my ability. The

white board humped up against the sky was a most conspicuous landmark, but it was far away and distant,

and the immediate surroundings were too attractive to allow of a divided attention. The air was heavy with the

beguiling odour of many flowers, for here flowers are cultivated just as cereals are on farms elsewhere. Roses, in

their season, are grown for the making of rosewater, and herbs for the great druggists, perfumes, and distillers of

London. It was not these things however, which gave the place its charm – although they helped – but the old-

world appearance of many of its cottages and their air of complete detachment from the bustling world outside.

AN ELIZABETHAN RELIC

Through open doors women could be seen preparing the midday meal in kitchens where men might have sat and

supped in the days when Sir Walter Raleigh rode daily past with a neighbourly salute. Even the close proximity

of quite modern brick cottages could not destroy the illusion that this was a bit of Elizabethan England which had

somehow survived intact when it might reasonably be supposed to have perished. Still, this was not Lonesome,

and it was not until the Beehive was reached that I encountered the first promising clue.

On a board fixed to the end of a house was this inscription : “Footpath to Eastfields and Lonesome”. The footpath

lay between the gables of two houses, and was so narrow that two persons of only moderate corpulence could

not have passed without occasioning each other some discomfort. It ended in a road full of ruts, with fields on

either side covered with huge glass frames wherein flowers were being forced. It was moreover, a deceptive

footpath, for, instead of leading straight into Lonesome, as might have been supposed from the announcement

on the sign-post, it ended at a railway crossing and signal box.

A slatternly young woman, dallying by the side of the path with an uncouth lad, has never heard of the elusive

village I was in search of, and I began to wonder if it was not like the strange “Half Town” of Celtic romance,

which mortal eyes have never looked upon. It was here that an end was put to all my difficulties, and I got at

last on the straight road to “Lonesome”. A cycling police sergeant was my ultimate guide. “After the ghost?”

he asked, laughingly, when he had given me full and complete directions. I had not heard of the ghost, but at

once a wraith of some sort seemed to be the necessary equipment for a village with such a name.

I threw out this hint to the sergeant, but he was boisterously sceptical. “Don’t you bother about it,” he said, “it’s

only a big swan.” No doubt the matter-of-fact sergeant was right, but it was with a keen feeling of disappointment

that I accepted his explanation. Lonesome without a ghost seemed incomplete and unsatisfactory; it was not

living up to its name or fulfilling its destiny in the world.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 14

COLLAPSED HOUSES

It is not a deserted village in the fullest sense of the term, yet it has an aspect which readily accounts for its

name and explains its ghost. Right on the edge of Lonesome Wood is a double row of big houses, upon whose

hearths a fire has never been lit, and over whose thresholds no footstep has ever passed. They are approached

by a weed-strewn, deeply-rutted road, from which they are fenced off with a dilapidated iron railing. The broad

roadway which separates the two rows is covered with high grass and weeds. Each house looks as if it required

only a vigorous push to send it to the ground. One roof, indeed, has already fallen in. Intending occupants cannot

be numerous and the following inelegantly-worded notice is presumably intended for tramps who might be

disposed to seek a night’s shelter in one of the houses.

CAUTION

Any person trespassing on these premises do so at their own risk, as these buildings are dangerous, and any

person trespassing will be prosecuted by the police.

A more melancholic example of the risks of speculative building could not be conceived. As for the rest of the

village, its character may be imagined when I say that there is one butcher’s shop, where meat is sold only in the

form of sausages. All other kinds have to be brought in. For the rest it is less like a typical English village than a

suburban offshoot from a big town which has somehow got stranded in an out-of-the-way corner of its county.

There is an easier but a less interesting way of reaching the village of Lonesome than the one I have endeavoured

to describe. It is not so remote from London as the wildness of the common round about it would suggest. I have

not yet given away the geographical secret, but when I say that a thirty minute journey from Mitcham Junction

brought me back to London Bridge, many guesses should not be necessary to find it on an Ordnance map, the

only kind of map on which it is given a place.

left: Longthornton Road map 1867 Ordnance Survey

below: Longthornton Road Map 1893-4 Ordnance Survey

Longthornton Road Blakes Follies Longthornton Road Blakes Follies

Daily Mirror 28 November 1913 detail Daily Sketch 20 November 1905

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 15

HAVE YOU PAID?

Subscriptions for 2014-15 are now overdue. Please note that this will be the last Bulletin to reach you if

we have not received your payment by the time of the next issue.

A membership form was enclosed in the September Bulletin. Current rates are:

Individual member £10

Additional member in same household £3

Student member £1

Overseas member £15

Cheques are payable to Merton Historical Society and should be sent with completed forms to our

Membership Secretary.

EMAIL THE EDITOR

Please note that articles and comments may now be sent directly to the Editor by email at editor@

mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk

Letters and contributions for the Bulletin should be sent to the Hon. Editor, Mr David

Haunton, or by email to editor@mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk The views expressed in this

Bulletin are those of the contributors concerned and not necessarily those of the Society or its

Officers.

website: www.mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk email: mhs@mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk

Printed by Peter Hopkins

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 192 – DECEMBER 2014 – PAGE 16

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY