Bulletin 166

June 2008 Bulletin 166

The First Raid on Merton Part 2 Where the Bombs Fell D Haunton

Musings on Merton Water-Names D Haunton

A Tudor ‘Plott’ in Morden C Maidment

Richard James Wyatt: ‘Accomplished Sculptor …’ J A Goodman

and much more

PRESIDENT: Lionel Green

VICE PRESIDENTS: Viscountess Hanworth, Eric Montague and William Rudd

BULLETIN NO. 166 CHAIR: Judith Goodman JUNE 2008

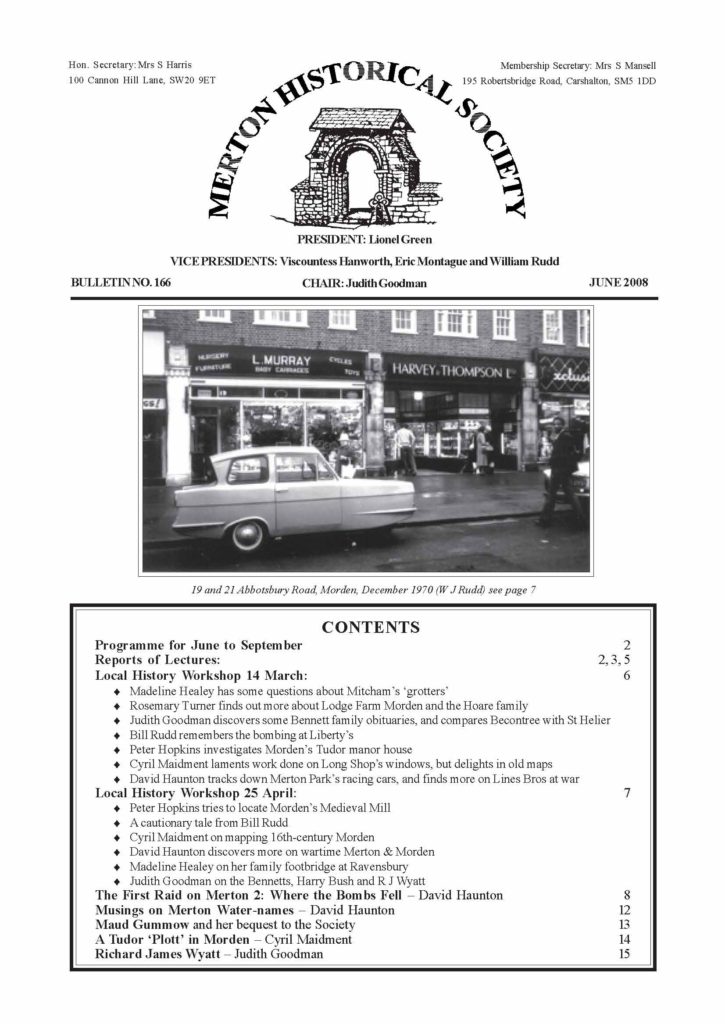

19 and 21 Abbotsbury Road, Morden, December 1970 (W J Rudd) see page 7

CONTENTS

Programme for June to September

Reports of Lectures:

2

2, 3, 5

Local History Workshop 14 March: 6

.

Madeline Healey has some questions about Mitcham’s ‘grotters’

.

Rosemary Turner finds out more about Lodge Farm Morden and the Hoare family

.

Judith Goodman discovers some Bennett family obituaries, and compares Becontree with St Helier

.

Bill Rudd remembers the bombing at Liberty’s

.

Peter Hopkins investigates Morden’s Tudor manor house

.

Cyril Maidment laments work done on Long Shop’s windows, but delights in old maps

.

David Haunton tracks down Merton Park’s racing cars, and finds more on Lines Bros at war

Local History Workshop 25 April:7

.

Peter Hopkins tries to locate Morden’s Medieval Mill

.

A cautionary tale from Bill Rudd

.

Cyril Maidment on mapping 16th-century Morden

.

David Haunton discovers more on wartime Merton & Morden

.

Madeline Healey on her family footbridge at Ravensbury

.

Judith Goodman on the Bennetts, Harry Bush and R J Wyatt

The First Raid on Merton 2: Where the Bombs Fell – David Haunton 8

Musings on Merton Water-names – David Haunton 12

Maud Gummow and her bequest to the Society 13

A Tudor ‘Plott’ in Morden – Cyril Maidment 14

Richard James Wyatt – Judith Goodman 15

PROGRAMME JUNE–SEPTEMBER

Tuesday 17 June 11.30am Goldsmiths’ Hall

Group visit to exhibition ‘Treasures of the English Church’, which is free.

Contact the Secretary to book.

Saturday 5 July Coach trip to Waterperry Gardens and Sulgrave Manor

This trip is now fully booked.

Thursday 7 August 1.30pm Guided tour of Wellcome Collection,

Euston Road NW1

The visit is free.

Contact the Secretary to book.

Wednesday 17 September 2.30 – 4pm Guided walk in Merton Park

The walk, led by Judith Goodman, will start from the war memorial outside St Mary,

Merton Park. It is part of this year’s Merton’s Celebrating Age Festival and is free, but

numbers are limited.

Contact the Secretary to book

‘HISTORICAL PUBS OF MERTON’

At our meeting on Saturday 9 February in St James’s Church hall, Martin Way, the speaker was member and author

Clive Whichelow. The talk was based on his book Pubs of Merton (2003), which is now available through the

Society, with information updated to the present day. His talk was both informative, based on research, and entertaining,

with amusing and interesting stories associated with many of the pubs. It was amply illustrated with slides, although

they were not seen to their best advantage, as it was a bright sunny day and the hall had several uncurtained windows.

Clive took the audience on a ‘pub crawl without leaving the building’, starting in the far west of Merton at the Earl

Beatty in Motspur Park, built in 1938. This pub was named after an Admiral of the Fleet, and Clive remarked on how

many pubs in Merton had naval associations. He then moved on to theDuke of Cambridge at Shannon Corner, built

in 1925, which benefited from the building of the new Kingston Bypass soon afterwards. It was once owned by the

Kray twins. It is now Krispy Kreme Doughnuts. He then moved east to the Emma Hamilton at Wimbledon Chase,

which opened in 1962. The name, unique in this country (although there are pubs called Lady Hamilton), was chosen

after polling members of the public.

Next, he came to Merton Park, and the Leather Bottle in Kingston Road. The present building dates from the end

of the 19th century, replacing a small 18th-century alehouse close by. The name is thought to have been chosen to

attract agricultural workers, who drank from leather bottles in the fields at that time. Clive also mentioned small beer-

shops at The Rush, now gone, that sprang up after

the 1830 Beer Act made it much easier for shops to

obtain licences to trade as alehouses. He then moved

on to the White Hart, by the tram crossing, one of

the oldest two inns in Merton, dating from the 17th

century. At one time Merton’s village fair was held

here, and the inn also gave its name to Hartfield Road.

Clive told the story of how in the 1930s the pub was

nicknamed the ‘Rope and Gun’, following two suicides

by bar staff – one hung himself, the other shot himself.

It was rebuilt after being bombed during the war, and

has survived a spell as ‘Bodhran Barney’s’ (it has

more recently suffered a further indignity, being painted

a horrific chocolate-mauve colour). White Hart c.1910, courtesy Keith Every

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 2

Clive moved on to the pubs close to South Wimbledon station. The Grove Tavern was built in 1865, and rebuilt in

1912. It was named after Sir Richard Hotham’s Merton Grove estate that was across the Kingston Road. The

application to rebuild was approved by the local magistrates subject to the condition that the new building included

ladies’ toilets – this was said to be an entirely novel unheard-of requirement. Then, a short way along Merton High

Street, the story was told of the 19th-century Kilkenny Tavern, once the Horse & Groom. This had changed name

several times, but had always been known by its nickname ‘The Dark House’, perhaps because it faced north and

was gloomy inside. Further along the High Street stands the Nelson Arms. A pub was established here in 1829, to

be replaced close by in 1910 by the current building, with its fine tiled exterior. Clive contrasted the interior today with

what it must have been like when described in a book in 1926: ‘… as enchanting a hostelry as anyone might wish to

beguile his time in … everything conducive to suggest a superior clubhouse’.

At the far eastern end of Merton High Street Clive apologised to the serious local historians present for stepping just

outside the old parish of Merton, mentioning several recent sad changes: the closure of the old inn, the King’s Head, and

its conversion to bus company offices (next to the bus garage); the disappearance of the name of the old coaching inn, the

Royal Six Bells, with three subsequent modern ‘wine bar’ names; and the change of name (in Nelson’s bicentenary year,

no less) of the Victory to the Colliers Tup. To add to the competition faced by pubs near Colliers Wood, a new one, Kiss

Me Hardy, with its extension Wacky Warehouse, has been built. Clive noted that ‘Kiss me, Hardy’ were Nelson’s dying

words, although some have doubted it, but he never said ‘Wacky Warehouse’ – of that there is no doubt.

Clive then continued his virtual tour, moving on to pubs south of the High Street. Several were built in the 1850s and

1860s to serve the population of the workmen’s small houses on what had been Nelson’s Merton Place estate,

including the Corner Pin in Abbey Road, later Uncle Tom’s Cabin – closed in 1907. Two pubs have survived the

slum clearances of the 1950s and are now popular, traditional real-ale pubs: the Princess Royal and the Trafalgar

Arms. Nearby is a relatively new pub, the William Morris, at Abbey Mills. Morris’s workshops were close by, but

not at this site – the former Liberty printworks. Under the terms of the establishment of the Abbey Mills venture

Liberty & Co vetoed the use of their name in any promotions.

The talk ended with an account of the history of two pubs in Morden Road. The Nag’s Head was said to have been

built using material from the demolition of Nelson’s mansion, Merton Place. The pub was demolished in 2001 for

redevelopment. The 19th-century Prince of Wales, further south towards Morden, was under threat of closure in the

mid-1990s, as the owners, Young’s, had received a good offer for the land. Following protests by the regulars, who

included cast and crew of the TV programme The Bill, it was decided to keep it open. It just so happened that this

decision was made at about the time of the sad death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997. Young’s announced that

the pub would stay open and that it would be renamed the Princess of Wales. The new sign shows Diana’s symbol

– the white English rose.

David Roe

‘LONDON MARKETS, MARKET HALLS AND EXCHANGES’

On 1 March Professor David Perrett gave a superbly-illustrated talk to a near-capacity audience at Raynes Park

Library Hall. He revealed that his interest in markets was sparked by his daily walks through the buildings of Smithfield

Market to and from Barts Hospital, where he is Professor of Bio-Analytical Science.

To set the scene, we were introduced briefly to the types of market – retail, wholesale and exchange – and the range of

owners – the Church, the lord of the manor, corporations, trustees and private landlords. Markets are regulated by

Statute, specifying the day(s) on which they may be held, and the times between which they may be open. There are

often local laws as well, whose particular interest is in providing for the market clock – no market is without one. The

rules, weights and charges, and good order are enforced by beadles, inspectors, and independent police forces (giving

us the QI question ‘how many police services are there in London ?’, the answer being ‘the well-known Metropolitan,

City and Parks, plus one for each public market’).

In medieval London, all markets were within and regulated by the City. These were mostly street markets, with very strict

boundaries; now only the names remain – Cheapside (for chapmen, i.e. small traders), Milk Street, Poultry, Bread Street,

Gutter Lane (drains for the butchers…) and the Haymarket (very wide to accommodate bulky wagon-loads). The Church

financed the building of London Bridge by rents from a market on its southern end, and even today the City boundary

extends across the bridge and around its south abutment, where the market was held.

Much changed from the 1840s, when new building materials became available, such as wrought iron and large

sheets of glass, allowing the construction of enclosed market halls with large span roofs. Glazed tiles appeared,

which could be washed frequently, giving much improved hygiene. Transport was much speedier with the railways

now able to bring fresh food overnight from as much as 100 miles away, and London no longer had to depend on

market gardens (note the phrase) close to the city.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 3

Civic and trade pride ensured that many new

market buildings were appropriately

decorated; in London the survivors include

the Leather Exchange in Bermondsey (1873),

with many carved roundels on the outside

illustrating the trade, and the Hop Exchange

in Southwark Street (1867) with a carved

pediment above the elaborate ironwork gates

leading to its galleried interior. Sadly, the castiron-

framed Coal Exchange in Lower

Thames Street (1847) was demolished in

1962 and the free-standing heraldic dragons

(or are they wyverns ?) on its boundaries

are all that remain.

The major wholesale markets go back a long

way. Billingsgate (1016), Smithfield (1173)

and Leadenhall (1377) were Corporate

markets, while Covent Garden (1656) and

Spitalfields (1682) were privately owned.

We looked at the history of Smithfield in some detail. It began in 1173 as a Friday horse market in ‘Smoothfield’, but

quickly became a meat market, to which animals were driven on the hoof, and where they were slaughtered, skinned and

butchered. In 1683 the 3-acre open space was at last paved, drained and railed in, but it was too small. In 1725 Daniel

Defoe recorded that some Smithfield butchers were travelling miles up the drove roads out of London to where they met

cattle drovers and bought their stock, thus ‘forestalling’ the market. By 1731, Smithfield covered 4½ acres, by 1834 6¼:

and was still too small for the amount of trade. In 1846 nearly two million animals were slaughtered. The nuisance was

enough to enable the Smithfield Market Act (1852) to move the market to Islington in 1855, where a vast rectangular

area was built, walled and drained, with a 150-ft clock tower in the centre and a large pub at each corner (“pubs very

important to markets” said the Professor). However, the market butchers disliked Islington and ‘did a deal’ with the City:

Smithfield became a dead-meat market (ie. no slaughtering) on its old site, in a new colonnaded iron-framed structure,

which also housed shops and restaurants. The meat now arrived on the Metropolitan Railway, below the buildings, and

was transferred onto horse wagons which carried it up a wide and gently sloping spiral road (still there) to the market.

And so it worked until closed ten years ago by EU Health and Safety regulations.

Change was continual for London markets: in 1825 Borough Market was established under trustees (the only such

market in London) to replace the old London Bridge Market; in 1878 the first shipment of frozen New Zealand lamb

arrived to be lodged in the Port of London Cold Store at Smithfield; Leadenhall Market was rebuilt in 1881; King’s Cross

Potato Market, built in 1850, was rebuilt in 1896 so that the trains from Lincolnshire could discharge their spuds down

through chutes directly onto the market floor below.

However, Hungerford Market was demolished in 1860 (Charing Cross Station stands there now), Columbia in 1958,

Brentford in 1981 and Stratford Vegetable Market in 1990. Greenwich, Woolwich and Smithfield are all under threat.

The future looks bleak for market life, though it still flourishes at Borough, Camden, Portobello and both original and New

Covent Garden Markets.

* Local Note The fruit and vegetable stall by Wimbledon Library represents almost the last vestige of Wimbledon’s street market.

It is run by Mick Ferrari, who still drives to New Covent Garden Market at four o’clock every morning for his produce.

David Haunton

Billingsgate Market in 1858, drawn by William McConnell

to illustrate G A Sala’s Twice Round the Clock

The London General Omnibus

Company’s prize omnibus, 1856

(see report on facing page)

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 4

‘A SOCIAL HISTORY OF THE LONDON BUS’

John Wagstaffe, who worked for 30 years for London Transport and its successors, gave us a quick historical

tour of the London bus ‘from Shillibeer to Bendy Bus’, beginning with the naming of the ‘bus. One suggested

origin of the term ‘omnibus’ (literally ‘for all’) arises from a very early courtesy services in Nantes, France, run

by a certain Stanislaus Baudry to bring customers to his grocery store, for which the starting point was outside

M. Omnes’ shop – hence by a Latin pun ‘from Omnes’, or Omnibus.

The first bus in London was started by George Shillibeer in 1829 in imitation of continental bus services. He was

originally a designer of horse-drawn carriages, especially hearses, and called his first vehicle not an Omnibus

but ‘The Economist’. It ran from Paddington to the Bank of England via the ‘New Road’ (now Marylebone

Road / Euston Road), as the City Fathers would not allow it to run through the city because of congestion.

Although there were established ‘short stage’ coaches, such as one from Richmond to London (taking almost

two hours to Hyde Park Corner), his innovation was to use shorter routes, with regular and frequent services

which did not have to be booked in advance. Fares were not cheap, a shilling for a single journey or sixpence for

part way, and were intended for the middle classes. The working classes had to wait for the arrival of trams

before they could afford to travel other than on foot.

Using contemporary illustrations, John showed us the development of the bus from the original single-deck

coach with 16-20 passengers inside, via the ‘knifeboard’ and ‘garden seat’ double-deck but open-top buses, to

the introduction of motor buses (initially petrol, but with some early steam and electric vehicles) in 1908. The

last horse bus ran in 1914 although horses continued to pull trams until much later. Owing to Metropolitan Police

Regulations, there were no windscreens on early motor buses (windscreen wipers were not yet reliable), no

pneumatic tyres, and no roofs on double-deckers until 1930 (in case they might topple over with too many

passengers upstairs). Even bus stops were not introduced until the 1930s, when increasing congestion made it

impractical to stop anywhere.

During the First World War many buses were taken to Belgium for use to transport soldiers around the battlefields,

and these developed many interesting variations, including one shown performing duty as a dovecote for messenger

pigeons. Also, woman bus conductors, or ‘clippies’, were first used to replace men called up; however they

were not allowed to remain after the end of the war, and did not reappear until the Second World War. Women

bus drivers were not used until much later, owing to the physical strength needed before the days of power

steering and starter motors, and not least because of opposition from the male-dominated unions.

The initial bus services were all privately owned, but in 1856 several smaller firms combined to form the London

General Omnibus Company (LGOC) which eventually ran a majority of services up until the formation of

London Transport in 1933. The LGOC’s buses were all painted red, and hence the tradition, maintained up to

the present day, that the London buses are predominantly red in colour. Route numbers were not introduced

until around 1890 (by LGOC); prior to this buses were referred to by the company name running the service, or

(more commonly) the colour of the bus, every operator having his own livery.

‘Greenline’, or limited-stop express services, were introduced in 1930, and diesel buses (always referred to as

‘oil-engined’ or ‘oilers’) also began to appear then. During the Blitz many buses were destroyed or damaged,

although proportionately more trolleybuses suffered than motor buses, possibly because of the routes on which

they were used being mainly through industrial or working-class districts. After the war a new bus called the

Routemaster was designed especially for service in London, and despite the initial proposal to remove then

from all services because of their lack of disabled access, a few can still be seen on ‘heritage’ routes 9 and 15

in central London. The Bendy Bus is the most recent innovation in technology, designed with disabled access in

mind, but proving to be unpopular with other road users; according to the latest proposals no further routes will

be converted to Bendy Buses.

Finally John mentioned the countrywide deregulation of bus services in the 1990s, from which London was fortunately

excluded, following representations from London Transport that this would result in chaos – as was indeed demonstrated

in other major cities, such as Glasgow. Although the bus fleets and garages were sold to private companies, the

services (routes, frequencies etc) continued to be determined by LT’s successor Transport for London.

In a wide-ranging discussion after tea, topics raised included special low-height buses on route 127 (because of

a low bridge at Worcester Park), private feeder services run by estate developers before there was sufficient

demand to justify a public service from LT, special curved-roof buses to fit into the Blackwall Tunnel, and the

origin of adverts on buses. In all of this John showed his encyclopaedic knowledge of all things bus-related, and

gave a very informative presentation on the subject.

Desmond Bazley

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 5

LOCAL HISTORY WORKSHOPS

Friday 14 March, afternoon meeting. Seven present. David Haunton in the chair.

.

A letter in the local press had reminded Madeline Healey of the little ‘grotters’ that Mitcham children

used to set up in the streets before Mitcham Fair, in the hope of collecting pennies from passers-by. Her

father had made one for her, using mud and china fragments and incorporating a tiny arch and a statue of

the Virgin Mary. She had come across a theory (mentioned in Eric Montague’s Pictorial History of Mitcham)

that the grottoes were connected with the Feast of St James (25 July). Can any reader confirm this?

.

Rosemary Turner had returned to the Hoare family and their connection with Lodge Farm, Morden.

London Metropolitan Archives have a map of the estate, with numbered plots. She had found the relevant

Hoare wills difficult to read on the computer screen – which, at present, is the only access. She told the

meeting that there is an attractive watercolour of Lodge Farm at the Merton Local Studies Centre.

.

Judith Goodman, still working on the Bennett papers, had received from the family a copy of an obituary

for Canon Frederick Bennett, who put the family papers together. She had also found the Times obituary of

Bennett’s cousin John Mackrell. His brother and he were the successive owners of the Merton Abbey

estate for 78 years.

On a visit to Becontree, the LCC estate thought to be the largest municipal housing estate in the world, she

had been interested to compare it with the St Helier estate. Becontree, which is completely flat, is more

monotonous in design and has less greenery. Much of the housing however is (or was) attractive, including

some ‘butterfly’ houses, as at Morden, and some pleasant dormer bungalows in Valence Circus. On the

edge of the estate she spotted a Merton Road (see Bulletin 165, page 6).

.

David Haunton’s contribution to the last Bulletin had recalled to Bill Rudd that first bombing raid on

Merton in August 1940, which he remembered well. There was a listening post at Liberty’s, where he

worked at the time.

.

Peter Hopkins spoke again about Growtes, the old manor house of Morden, that stood more or less on the

site of the present Morden Lodge. (The name comes from an early owner, John Growte.) He invited the

meeting to compare the 1554 inventory, at Surrey History Centre, with a 1753 Hand-in-Hand insurance

policy details of ‘a timber house etc on the east side of a road leading from Morden to Mitcham’ at the

London Guildhall Library. Members were pretty well convinced that the same building was concerned in

these documents separated by 199 years.

.

Cyril Maidment was sorry to report that the attractive

arched windows of the ‘Long Shop’ at Merton Abbey Mills,

which lacked any statutory protection, were being altered.

However, maps and what they can tell us were Cyril’s

main theme: the interesting, but undated, map of Essex

Henry Bond’s estate in Merton; Rocque’s map of 1746,

with a pond at Merton Place and a stream flowing into

the Wandle; Norden’s map of 1594 compared with one

of 1951; and, with its glimpse of part of Tudor Morden,

the map of c.1550 relating to ‘Sparrowfield’, which is

reproduced in David Rymill’s Worcester Park book (and

elsewhere).

.

David Haunton had learned more about the miniature

racing cars at Merton Park Parade (Bulletin 165 p.7). The

Palmer-Reville ‘Special’ won a medal in 1933 and their

‘Gnat’ was famous as the world’s smallest racing car.

He had also discovered more about Lines Bros of Merton.

By chance he found that the Museum of Childhood at

Bethnal Green have much archive material from the

company, including photographs of women making the

aircraft recognition models (Bulletin 164 pp. 12-15 and

Bulletin 165 p.10). Lines also constructed, for the

Admiralty, models of the Normandy landing beaches.

Judith Goodman

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 6

? overgrown mill-pond? ? overgrown mill-pond?

Friday 25 April 2008, evening meeting. Six present. Judith Goodman in the chair.

.

Peter Hopkins sought advice on the location of Morden’s medieval watermill. Its pond, weir and leats are

likely to have influenced the local landscape for centuries. Of the three later millsites, Ravensbury Mill can

be discounted, as it lay in the manor of Ravensbury, not the manor of Morden. Peter would like to believe

that the Watermeads area was the site of the Saxon mill – why else would the parish boundary protrude into

Mitcham and Carshalton? – and the line

of Paper Mill Cut was already a field

boundary before the papermill was built.

But it wasn’t part of the Morden

demesne lands in post-medieval times,

and may have been lost long before.

The Morden Hall snuffmills occupy the

third site. Peter observed that the river

bulges between the islands and the millrace

– could this be the remains of the

medieval mill-pond? It was already

partially filled with an osier bed when

this, the earliest map, was drawn in 1750, but that had been cleared away before the later maps.

.

Bill Rudd told a cautionary tale of newspaper reporters. A recent letter, about local shops, to the local

Guardian led to a request for an interview, but the resulting article managed to replace nearly all Bill’s

carefully assembled facts with errors! Fortunately a letter to The Post appeared in full on 24 April.

.

Cyril Maidment had been busy identifying landmarks shown on a 16th-century map of Morden, Cheam

and district, and placing them on a modern map. See his article on p14.

.

David Haunton has been furthering his researches into wartime Merton. He was very pleased to have

been able to identify the ambulance depot shown in a photograph acquired by Judith Goodman. Looking

through inspection reports at The National Archives, he discovered there were only three such depots in

Merton and Morden – at the pavilion in Morden Recreation Ground, at Morden Farm School in Aragon

Road, and at the rear of Aston Road Library in Raynes Park. He then found a similar photograph of the

Aston Road depot in the Merton and Morden News for 5 April 1940 (to be illustrated in the next issue).

David also reported on the first bombing raid (see article on pp 8-11), and on further developments regarding

the target gliders made at Lines Bros. The Lines archive in the Museum of Childhood includes a letter from

the Royal Australian Airforce asking for details so that they could make some. One is in Queensland Air

Museum, who put David in touch with a Triang toys enthusiast in Dartford. He has a collection of toys,

including one of the rocket-powered glider made to train Merchant Navy gunners (see Bulletin 163 p8).

.

Madeline Healey has been reminiscing with relatives and was told about the wooden footbridge that her

grandfather, father and uncle made on Mr Hatfeild’s instructions so that pedestrians could safely walk along

the road between Ravensbury Mill and The Surrey Arms. The humped road bridge had no rails, and someone

had fallen in. This was around 1936, before Madeline’s time. Does anyone else remember it? Later the

stream was diverted under the road, but the car-parking space in front of the houses was then water.

.

A holiday in Wiltshire had provided Judith Goodmanwith the opportunity to visit two sites connected with

the Bennet family, whose letters and papers she is preparing for publication. Canon Frederick Bennet, who

created the collection, was curate and then vicar of St Mary’s Maddington for some 50 years, and married

a relative of the lord of the manor, John Maton. Judy showed photos of the church and of Canon Bennett’s

memorial plaque. Not far away is Collingbourne Ducis, the seat of the Mackrell family, related to the

Bennetts and to the Smiths of Abbey Gate House.

Judy also showed photographs of Harry Bush’s drawings for his oil painting A Corner of Merton 16

August 1940 (see p10) and others of the same period.

She also told us that one of the sculptures by R J Wyatt is on display at Tate Britain until 8 June, on loan from

Nostell Priory. Son of Edward Wyatt of Merton Cottage, he created the Smith and Cragg family monument

in St Mary’s church. Most of his working life was spent in Rome, so there are only a few pieces in Britain,

including one at Chatsworth, and a couple in the Queen’s collections (see pp 15-16).

Peter Hopkins

Next Workshops: Friday 20 June 2.30pm and Friday 15 August 7.30pm at Wandle Industrial Museum

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 7

DAVID HAUNTON’S name was inadvertently omitted in the March Bulletin as author of The First

Bombs on Merton Part 1. Though many readers will have been able to guess the authorship we offer

him profound apologies. Here is

THE FIRST RAID ON MERTON PART 2: WHERE THE BOMBS FELL

To re-cap: the first Luftwaffe attack on our district struck two widely-separated areas in the late afternoon of

Friday, 16 August 1940. This article aims to record all the bombs that fell on Merton in that first attack. Thus it is

in essence a list, and perhaps less exciting than Part 1. Some details previously appeared in the Newsletter of The

John Innes Society for November 2006 under the title ‘Bombs on Merton Park’.

Sources

What happened in Merton can be described rather more factually than the events in Part 1, but even so our

evidence is surprisingly slender. During the war, it was the local authority’s responsibility to record the fall of

each bomb, and its effects in terms of damage and casualties. A summary was reported to the controlling Civil

Defence Region, where bomb locations were plotted on maps, which do survive. Unfortunately for our present

purpose, the central summary records were only retained for incidents occurring after 31 December 1940.

Even more unfortunately, the detailed local records for Merton and Morden Urban District were discarded

when the London Borough of Merton was formed in 1965 – no public-spirited and/or indignant person took

them home to preserve them (as happened in Wimbledon).1

So far as official records go, we are left with the contemporary central map, which locates all bombs dropped

between 16 August and 6 October 1940,2 plus a local authority map, compiled after the war, apparently with

some casualness, of every bomb dropped on the District during the entire war.3 Both maps give bomb location

dots but little other information. To these we may add a few understandably tight-lipped notices from Council

minutes, mostly about repairs.4 All else depends on reports in local newspapers (circumspect because of

censorship),5 a few published notes and the memories of folk who were there, supplemented by local street

directories6 and some personal observation of buildings. Please note that when I say a bomb landed ‘near’ an

address, this represents my best guess at reading details from a very small map. Building repairs have mostly

been in character, so there is little evidence visible on the ground.

Bombs In the West

During the raid, three quarters of the bombs dropped in the west fell within the Borough of Malden and Coombe.

The other 44 or 45 bombs fell on Merton, in a ragged cluster extending from West Barnes north-east across

Grand Drive and the playing fields as far as Bushey Road.

Only four bombs hit Merton west of the Kingston Bypass. These fell south of Burlington Road, on an area

occupied by the Young Accumulator Co. works and a petrol station. However, over a dozen bombs hit residential

streets immediately to the east of the Bypass. The first fell on The Kingston Caravan Co. at the junction of

Stanley Avenue and the Bypass (where there is now a car-dealership). The date of the bomb near 2 Cobham

Avenue is uncertain: it may have fallen on 16 August, or on a later day. Two bombs fell in back gardens between

the north ends of Byron and Consfield Avenues, three between Consfield Avenue and the northern half of Errol

Gardens, one near 24 Errol Gardens (a block of four flats), two near 17 and 23 Barnard Gardens (similar four-

flat blocks), one between Barnard Gardens and Belmont Avenue, and one on 3 Cavendish Avenue. In June

1945 the owner of this last house complained to the Council about the use of his (heavily damaged) property by

repair contractors, for storage and tea-breaks, etc. (a common practice), and then complained again in December

1945 about the standard of its repairs. Externally, the house shows no differences from nearby properties.

Further north, across Burlington Road, one bomb fell in the grounds of The Sacred Heart Roman Catholic

School (“mixed & infants”, closed for the summer holiday) and six in the adjoining industrial area, which was

occupied by Bradbury Wilkinson (the banknote printers), four smaller concerns, and three local shops. A little

further north, two other bombs landed with amazing accuracy in the Pyl Brook, between the Bypass and West

Barnes Lane. Perhaps of more concern to locals was the ‘Duke of Cambridge’ pub as a target – two bombs

landed in the garden behind, and one just across the road in front. “All the windows” were blown out and a

summerhouse wrecked, but the local paper reported “no injuries in the hotel”. Though this was strictly accurate,

on Shannon Corner opposite, a man was killed while using a public telephone booth, and nearby a policeman in

a one-man police box was injured.

Potentially more serious were the two bombs that just missed the Motspur Park railway line, one beside the

level crossing where West Barnes Lane meets Burlington Road, the other about 100 yards further south. The

first one demolished the West Barnes Crossing Signal Box, where the signalman saw the bombs coming and

threw himself flat on the floor. Not seriously hurt, he was rescued from the rubble by the Auxiliary Fire Service.7

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 8

All the railway telephone and telegraph wires were cut, and the railway lines were blocked until later in the

evening, but traffic was not otherwise affected.8 The local paper claimed that, alerted by the sirens, nearby

shopkeepers had urged passers-by into their premises, so no serious injuries had resulted.

East of the railway, two bombs landed in open ground now covered by the southern end of Linkway (which was

extended after the war), but others hit residential streets. There were two in Brook Close (on 14, which was

destroyed, and near 2, perhaps in the back gardens of 195/197 Westway), three in Linkway (on 62, also

destroyed, just across the road near 63, and further down near 23), and yet another near 14 Coppice Close. We

know the two houses were destroyed because, after the war, in June 1946, their owners were given licences to

rebuild them. Both have been rebuilt, with some care to match their neighbours.

Thereafter, four bombs were scattered across Prince George’s Playing Fields, two more landed on Bushey

Road (one on either side of the line of Carlton Park Avenue), while the last one landed in the open ground

between Bushey Road and the end of Vernon Avenue.

Bombs In the East

In the eastern area attacked by the raiders, some bombs fell in the Borough of Wimbledon, but the majority,

some 75 bombs, fell on densely populated parts of Merton.

We have one bomb on the railway, close by the signal box at Merton Park level crossing. Norman Plastow

records that this bomb with a long delay fuse made a kink in one rail and a deep hole in the railway ballast. The

hole was speedily filled in by a railway worker, unfortunately without first extracting the bomb. Thereafter, a

Bomb Disposal Unit was summoned, which carefully dug down towards the bomb; the soldiers were taking a

breather (“cup of tea in a local café” according to Hubert Bradbury) when it exploded, just before midnight on

Sunday 18 August, after a delay of 54 hours. However, the BDU team were out of range, and nearby houses

had been evacuated as a precaution, so there were no casualties. Much track was damaged, and the lines to

Tooting and Wimbledon were cut. Brooksbank reports “many HE bombs” on the station, but only one bomb

was actually plotted on Merton Park Station, just outside its front door. Altogether the damage, here and

elsewhere, was such that a shuttle service was put on between West Croydon and Mitcham, and normal

running of trains was only resumed at mid-day on Tuesday 20 August.

The above delayed-action device may also have been responsible for the damage to the adjacent properties

(‘Oriels’ at 146 Kingston Road and the ‘White Hart’ pub), though the latter may also have been due to a bomb

that so seriously damaged the shop at 142 Kingston Road (now the ‘White Hart’ car park) that it was left

vacant. I suspect this bomb was not clearly reported or plotted at the time, because only in December 1946 did

the Council note with some surprise that the property had been empty for so long, and serve the owner with a

Notice to Repair.

Next we have the bomb that hit the old Rutlish School, on the corner of Kingston Road and Rutlish Road (in

1940 only recently renamed from Station Road). Tom Kelley, then a pupil, recalls that this bomb landed on the

main entrance hall and corridor, damaging its walls and ceiling and the Art Room, and that patching up the

damage delayed the start of term. Again, no-one was hurt.

The administrative boundary with Wimbledon ran along Kingston Road, so the effects of the 18 or so bombs

dropped to the north of it have already been carefully recorded by Norman Plastow.9 The Borough of Wimbledon

formed part of the County of London at the time, so, pedantically, these were the very first bombs to hit London.

Let us here note bombs near the ends of Russell, Palmerston, Southey and Montague Roads, which produced

sufficient debris to block Kingston Road for a while and which inflicted minor damage on buildings on the south

side of the road, in Merton and Morden. These included the library, the Council offices and, ironically, the ARP

Report and Control Centre next door.

Many bombs fell in the residential streets just south of Kingston Road, where the terraced houses are more

densely packed, with smaller gardens, than those of West Barnes. In Shelton Road (where the houses are all on

one side and numbered consecutively) one bomb hit 3 or 4, damaging both severely, another fell on the junction

with Branksome Road, and others near 9 and 14. Hubert Bradley saw the crater of one of these in a front

garden, and still remembers the spectacular sight of a broken gas main on fire. Another bomb fell on the

junction of Shelton and Kirkley Roads, which may account for the changed porch roof at 9 Kirkley. There were

two in Winifred Road, near 10 and 20, while Mina Road suffered a small bomb in the road near 30, and a large

bomb which demolished or severely damaged 3-13 (the whole terrace 3-17 has been rebuilt post-war). Three

bombs hit Kirkley Road, on 18 (destroyed, now rebuilt), and near 25 and 39. Two more landed in the back

gardens of 2 and 28 Boscombe Road, while one fell near 71 Bournemouth Road, and another on the junction of

Bournemouth and Mina Roads.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 9

Further east, one bomb fell near 70 Melbourne Road, and three in Brisbane Avenue: one near 57, one (which

did not explode) on 51, and one which heavily damaged 29 (an obvious re-build). There were two in Milner

Road, one near 17, and one a direct hit on the electricity sub-station between 24 and 30, which put it out of

action. This cut the traction current to the local Northern underground line, but train services were only suspended

for two hours.10 One bomb fell on Morden Road a few yards south of Milner Road, one on Foster’s Engineering

Works, another on 2 The Path (damaged enough to be rebuilt, now part of an extended terrace) (see illustration)

and one in the large back gardens between Queensland Avenue and Morden Road. Four bombs fell in Bathurst

Avenue, one close by 2 (see Judith Goodman’s picture no.159),11 and two others, near 9 and 19 (a newish build,

with an odd join to 17). The fourth bomb landed in the back garden of 8, providing the subject of a painting by

Harry Bush (see detail sketch).

Drawing by Harry Bush

of the view from

Queensland/Bathurst

Avenues of bombed house

at No.2 The Path

Photo courtesy Imperial

War Museum,

reproduced by

permission of Diana

Robinson

Further east still, across Morden Road, between Merton High Street and the

Merton Abbey railway line, the bombers struck at an area where residential

roads were interspersed with light industry. This area was extensively redeveloped

after the war, and little now remains of pre-war housing, so my

bomb positions are even more approximate than usual. We can record two

bombs toward the High Street end of Haywards Close, one on Pincott Road

north of Nelson Grove Road, two some way south-west of the Pincott–Nelson

Grove junction, and three to the south and east of Rodney Place. One of these

hit the Omega Lampworks factory, while certainly one and probably both of

the others hit the Brett Bros packing case factory. For some years afterwards,

the corrugated iron fence around the Omega factory bore the scars of bomb

splinters. Along High Path, one fell opposite Merton Abbey School, which lost

most of its windows, one on the junction with Pincott Road, and one on either

side of the road a little to the east of Dean’s Rag Book works. Three bombs fell

in open ground between the Pincott Road junction and the railway. Unfortunately,

this was where the caravans of the Bond family of travelling fairground showmen

Drawing by Harry Bush of damage to a roof and conservatory on 16 August 1940

Photo courtesy Imperial War Museum, reproduced by permission of Diana Robinson

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 10

were parked, and where Caroline Bond, aged 19, was killed, and her mother

Mary Anne Bond was injured. Caroline was a night-shift worker at Venners

Time Switches factory on the Kingston Bypass, and was asleep in her caravan

at the time of the raid. Her grave in St Mary’s churchyard, Merton Park,

carries a tribute from her fellow workers.12

Down the east side of Morden Road, one bomb damaged the Congregational

Church Hall near the underground station (after repair it was used as a British

Restaurant), one landed near 25, and a third fell in Nelson Gardens public

park, damaging the windows and stonework of the church of St John the

Divine. This last one killed Mr Eaton, a St John ambulance-man, outside the

public shelter in the Gardens.

The Merton Abbey railway track was hit by three bombs, two alongside Lines

Bros, and a third nearer to Merton Abbey Station. These blocked both the

tracks and Lines Bros private siding, and blocked in a goods train actually on

the line. As mentioned above, normal working only resumed four days later.

Some bombs did land on the industrial estate. Seven or eight hit one of Lines Bros big factory buildings (the

northernmost of the three, next to the railway), but damage was light, confined to holes in the roof, with

suspended lighting and electrical cables blown down. Tarpaulins were slung over the holes and production

carried on. There were no casualties, as all staff were in their air-raid shelters. Given the short warning time

this was quick work, and speaks volumes for the standard of staff preparedness and organisation, as several

thousand people were then employed at the factory.

At least four bombs fell on Liberty’s sports field, doing no harm, but Liberty’s factory received three others, one

of which badly damaged the small brick-built works office and the large weather-boarded screen store, another

landed in the Wandle and the third one in the lagoon.13 Bill Rudd tells me that the sole casualty was the only

employee not yet safe in a shelter. This chap was hurrying through the Block Shop when the windows blew in

and he was slightly cut by flying glass. Staff came in over the week-end to tidy up and sweep away the glass,

and work resumed as normal on Monday.

South of the station, four bombs fell on the premises of some of the small engineering firms between Littlers

Close and the Wandle. Another fell at the far west end of Runnymede, where it severely damaged 202-208 (all

the buildings in this street are blocks of four maisonettes); licensed for rebuilding in 1946, the replacement block

uses the same plan but lighter-coloured bricks. The last bomb landed in the entry by the back doors of 73-75

(shown in two published photographs).14

Finally, we should note that the Mitcham local paper reported only one Mitcham house destroyed, empty

because the lady was out shopping, (I suspect that this was in Phipps Bridge Road) and, specifically, that there

were no Mitcham casualties.

Afterword

I warned you that this might be boring. But if you can expand or amend any detail on this list, please contact me.

I don’t bite. Honest.

1 Plastow, Norman Safe as Houses: Wimbledon at War 1939 –1945 (1972, revised 1990) The Wimbledon Society [Available in Merton

Libraries and highly recommended.]

2 The National Archives HO193/12 Sheet 56/18SW “Up to 6/7 October 1940”

3 The map may omit unexploded bombs. A surviving copy of it was found in The Wimbledon Museum by Cyril Maidment, who kindly gave

me a photocopy.

4 Minutes of Merton and Morden Urban District Council 1940-1947: Special (full) Council Meeting 20/8/40; Civil Defence Emergency

Committee 20/8/40 – 12/11/40, etc.

5 Merton and Morden News 23/8/40 and 30/8/40; Wimbledon Borough News 15/9/44; Mitcham News and Mercury 23/8/40 and 30/8/40;

Surrey Comet & South Middlesex Gazette 21/8/40 and 24/8/40

6 Kelly’s Street Directory for Wimbledon, Merton and Morden 1940

7 This incident has often been erroneously mentioned in connection with the Merton Park Crossing Box, probably because of the confusing

nature of the carefully non-located reports in the local papers. But Brooksbank (next footnote) clarifies all railway incidents that day, from

independent official notes.

8 Brooksbank B W L London Main Line War Damage (2007) Capital Transport p.11

9 Plastow op.cit.

10 Green, Lionel The Railways of Merton (1998) MHS p.39

11 Goodman, Judith Merton and Morden, A Pictorial History (1995) Phillimore.

12 Mr Bert Sweet, Society member and life-long Merton resident, looked for and found this memorial, having recalled his late wife speaking

of it. He also kindly recorded some other family memories for me, quoted elsewhere.

13 Rudd, W R Liberty Print Works – Wartime Remembrances (1993) MHS Local History Notes 8 p.5 See also Goodman op.cit. photograph 161

14 Compare Goodman op.cit. photograph 160, looking south towards Liberty Avenue, and Spencer, Adam (Ed) Merton: The Twentieth Century

(1999) Sutton Publishing and London Borough of Merton p.59, looking north to Runnymede.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 11

DAVID HAUNTON shares his

MUSINGS ON MERTON WATER-NAMES

… by a partial, prejudiced and mostly ignorant toponym-ophile.

Place- and river-names form some of our earliest documents, and can throw a little light in some corners of the

Dark Ages. In England, the majority of current place-names arose during the Anglo-Saxon period, roughly

500-1100 AD, and naturally reflect the dominant language of the time, which evolved into modern English.

These are overlaid by a later stratum of Scandinavian names (eg. Thorpe, Grimsby), and a still later lot, which

combine English and Scandinavian roots in the same name (the ‘Grimston hybrids’). Most of the remaining

names are earlier, originating with the speakers of the Celtic British language, which later evolved into Welsh,

Cornish and Breton. These include major rivers (eg. Thames, Tees, all the Avons, Darts and Derwents, etc.)

and a few significant places (such as Britain, Kent, Dover). For completeness, we should note that there are

just a couple of true Latin survivors from the Roman occupation (Catterick and Speen), and a few which

include bits of real Latin (eg. ‘colonia’ in Lincoln and Colchester), or Anglicised Latin (mostly those ending in

‘chester’). There remain the river Severn (Sabrina in Roman records), and London, which are as yet unexplained,

and may be even earlier.

Two of our Anglo-Saxon settlement names imply an abundance of surface water: Merton is a ‘farmstead by

a pool’ (first recorded in 967 AD), while Morden is a ‘hill or rise in marshland’ (mentioned in 969 AD). In our

area, we have five named streams, but it is a little surprising that there are so few. The largest, of course, is the

River Wandle flowing northwards from Croydon to the Thames. I was surprised to learn that ‘Wandle’ is a

back-formation from the name of Wandsworth. So what does ‘Wandsworth’ mean? It is an English name

denoting the ‘enclosure or enclosed settlement of a chap called Wendel or Wændel’, and first appears in a

charter of 693 AD, which is an impressively early and extraordinarily lucky survival. The same charter gives

the river as the Hlidaburna, and variations on this are later recorded as the Hydebourne (967),1 Ledebourne

(1230) and Lovebourn (1349). The meaning is either the ‘loud stream’ (from hlyde) or ‘sloping stream’ (from

hlid), either being appropriate to a river with the steep fall of 14 feet per mile. ‘Wandle’ did not come into

general usage until the 16th century, or about 800 years after the first mention of the river. So it looks as if

‘Wandle’ crept upstream over the course of the 15th century, consigning the ‘loud stream’ to oblivion on its way.

Could this give us a date for the beginning of more intensive industrial use of the river ?

The Graveney arises in Norbury and flows westwards to join the Wandle nearly opposite Haydons Road

station. This small stream marks the boundary between Mitcham and Tooting Graveney for some distance

west of Streatham Vale. It derives its name from that of a medieval landholding family, the Gravenals of the

12th and 13th centuries. Curiously, this adopted name echoes an actual Anglo-Saxon water-name meaning an

‘excavated or dug waterway’, implying a stream whose course has been straightened or is in some part artificial.

The Pickle, earlier the Pickle Ditch, appears to have been at some time a leat of the Wandle, perhaps originating

as an ‘improved’ spillway, though now with an independent flow. It leaves the Wandle about 100 yards below

Phipp’s bridge, dives into a culvert along Phipp’s Bridge Road and Church Road, and reappears north of

Meretune Way to rejoin the Wandle at Merton Bridge as quite a lively stream. The name is something of a

puzzle. I take leave to doubt the folk-explanation of a corruption of ‘Pike Hole’, the more especially since a

little way upstream is (or was) a pool called the Jack Pond. As ‘jack’ is a widespread alternative name for a

pike, is it likely that there would be two such names within a short distance ? Eric Montague offers an elegant

alternative which appeals. He traces the name from ‘pightle’, a corner of land, from the unoccupied corner of

Merton parish land separated from Mitcham Common by the stream. This land-name evolved into ‘pickle’, and

the stream then became the Pickle Ditch by association. (The OED gives “pickel mere”, ‘pond by a pightle’,

as a similar association.) After the area became known as Jacob’s Green, the ‘Ditch’ part of the name fell out

of use, so our water-feature ended up with a land-name.

To the west, the Beverley Brook rises in Sutton and forms the western boundary of Merton for a couple of

miles, eventually flowing into the Thames, where it forms the boundary between Barnes and Wandsworth. I

presume that the Beverley was not usefully navigable, because so much of its course marks local administrative

boundaries. It has a straight-forward Anglo-Saxon name meaning the stream (from licc) where beavers

abound. (Since beavers normally inhabit wooded areas, this should not be taken as the beaver-lea, which would

signify beavers in open, tree-free countryside.)

Finally, we have the Pyl Brook, flowing into the Beverley Brook through Morden. ‘Pyl’ had several shades of

Anglo-Saxon meaning, some of which are retained by its modern descendant ‘pool’ – a trout pool is always

well upstream, but a tidal pool is necessarily near the sea (as in Liverpool, and the Pool of London) – but its

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 12

main meaning was simply ‘stream’. On either side of the Bristol Channel, and in Cornwall, ‘pill’ still survives as

a local word meaning a stream or tidal creek.

Now we come to a most intriguing speculation. A ‘pyl’-name can also derive from Celtic, with a very similar

set of meanings – ‘pwll’ in modern Welsh is a pool or stream. But how could there be Celtic-speaking Britons

around here, preserving their water-name ? It is, after all, well known that very early Anglo-Saxon artefacts

are found in Mitcham, Beddington and Wallington, all with fine Anglo-Saxon names. Or so we thought: Mitcham

is the ‘big village’ (michel ham) and Beddington is the ‘settlement of the followers/family of a chap called

Bæda’, while Wallington looks the same as Beddington. But Wallington is now believed to mean the ‘settlement

of the Wealas’ or Britons. So it seems entirely possible that there were enough local Britons to continue using

their Pyl brook-name and eventually to transmit it to English-speaking neighbours; who kept alive a name that

has now been applied to this trickle of water for, shall we say, two thousand years?

A nice, thoroughly Romantic, speculation; but I do also like the notion that when we say the Pyl Brook joins the

Beverley Brook, we are actually saying that the Stream Stream joins the Beaver Stream Stream.

Sources

Nicholas Barton The Lost Rivers of London (1962) Phoenix House and Leicester UP,

republished (1982) Historical Publications Ltd, New Barnet

Derek A Bayliss Retracing the First Public Railway (1981, second edition 1985)

Living History Publications

Doug Cluett and John Phillips (eds.) The Wandle Guide (1997) The Wandle Group,

Sutton Leisure Services

E Ekwall English River-Names (1928) Clarendon Press, Oxford

A D Mills A Dictionary of English Place Names (1991) Oxford University Press

E N Montague Mitcham Histories No.9: Colliers Wood or ‘Merton Singlegate’

(2007) MHS and Merton Library and History Service

Oxford English Dictionary (second edition 1989) Clarendon Press, Oxford

Wilfred Henry Prentis The Snuff Mill Story (1970) Privately published

A L F Rivet and Colin Smith The Place-Names of Roman Britain (1979) Batsford

Curiously, Hidebourne was also the name by which the Falcon River was known until the eighteenth century. This stream lies in the next

valley, about a mile east of the Wandle, arising in Balham and Tooting and flowing to the Thames via Clapham Junction Station, nowadays

entirely within culverts.

MAUD GUMMOW and her bequest to the Society

Miss C E M (Maud) Gummow MBE, who served for many years as a senior council officer for the Urban

District of Merton and Morden, was a long-standing member of this Society, keeping up her membership when

she retired to Devon, and only relinquishing it after losing her sight. She died not long ago. Your Committee has

been very touched to learn that in her will she left the Society more than five thousand pounds.

In considering how best to use this generous gift, we are looking at the feasibility of buying a portable amplifying

system for use at our lectures. We also envisage drawing on some of the money to fund future publications in

a situation where, perhaps because of the number of illustrations, production costs are high.

We would be glad to receive members’ views on these suggestions, or other ideas, for suitable use of Miss

Gummow’s bequest.

JG

WANDLE INDUSTRIAL MUSEUM

Twenty-five years on from 1983, when it opened, Wandle Industrial Museum is proud to celebrate its

Silver Jubilee with a new exhibition Looking Back, Looking Forward. The Museum is at the Vestry Hall

Annexe, London Road, Mitcham, and is open every Wednesday 1 – 4 pm and the first Sunday of every

month 2 – 5 pm. Admission 50p adults / 20p children and senior citizens. Tel: 020 8648 0127

MERTON HERITAGE CENTRE

The new exhibition at The Canons, Madeira Road, is called On Common Ground and explores Travellers’

heritage in Merton. It runs from 3 June to 28 June.

From 15 July to 27 September Through the Eyes of a Child looks at childhood and toys in our local area.

The Heritage Centre is open on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays. Telephone 020 8640 9387.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 13

CYRIL MAIDMENT on A TUDOR ‘PLOTT’ IN MORDEN

Morden Common, for centuries, was a precious hundred-acre triangle on the west side of Pyl Brook. Adjoining

Morden Common on its west side were the 360 acres of Sparrowfield Common. A modern acknowledgement of its

existence is Sparrow Farm Road. The access to the use of this common was always a matter of dispute. The

commoners of Morden insisted they had common of pasture rights. In 1553 a husbandman of Morden, John Frysby,

confiscated and impounded a ‘distress’, probably a grazing animal, that had strayed into what he considered was the

Morden part of Sparrowfield. Tenants of the Manor of Cheam then drove cattle and beasts off Sparrowfield onto

Morden Common. To protect their rights, tenants and farmers of Morden commenced a lawsuit in the Court of

Augmentations. At the hearing, a plott (a map or plan) was tendered in evidence. This was found to be unsatisfactory

and three men were ordered to make a more perfect survey, a second plott. This was our good fortune because large-

scale maps at this time were few and far between. There is a wealth of information in the plotts, but it is difficult to

relate it to the neighbourhood we know, partly because North is on the right and not at the top as we are used to it.

Details from both plotts can be seen on page 15 of the St Martin’s Church publication Lower Morden and Morden

Park, prepared by Peter Hopkins. More detective work has also been done by John Pile. The accompanying

‘clarification’ has been produced, where the detail is presented in a more conventional manner and five modern

locations included to assist understanding.

A

‘clarification’

of a very

early

Morden

map,

prepared in

1553, for an

investigation

concerning

Morden’s

right of

access to

Sparrowfield

Common

Five modern

locations

(labelled in

brackets)

are included

to assist

understanding

The little

drawings,

labelled in

bold font,

have been

taken from

John Pile’s

tracings of

the original

1553

document.

Their

location is

not precise.

Some are off

this map, as

indicated by

arrows.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 14

There is just time to see Tate Britain’s free exhibition The Return of the Gods: Neoclassical Sculpture

in Britain before it ends on 8 June. Among the sculptures on show is one lent by the National Trust,

from Nostell Priory, Yorkshire. It is Flora and Zephyr, a charming work by

RICHARD JAMES WYATT: ‘ACCOMPLISHED SCULPTOR AND

EXCELLENT MAN’1

Born in 1795, R J Wyatt was a member of a dynasty which included several generations

of architects, engravers, carvers, surveyors, land agents and painters. His father Edward

Wyatt (1757-1833) was an important carver in wood and stone, and gilder, who worked

at Carlton House for the Prince of Wales, and later at Windsor Castle on the transformation

scheme undertaken there when the latter had become George IV. This work at Windsor

was directed by Sir Jeffry Wyatville (1766-1840), who had been born plain Jeffry Wyatt

and was Edward’s second cousin. James Wyatt (1746-1813), a first cousin once removed

of Edward, made his name as the builder of the Pantheon in Oxford Street, a spectacular

venue for balls and masquerades, and went on to become, though notoriously disorganised,

Surveyor-General and Comptroller of the Office of Works. Edward may have got the

lease of his premises at No. 360 Oxford Street, next door to the Pantheon, through

James. Downstairs was the shop, and upstairs the family lived. Here Richard James and

his siblings were born; they were baptised at the church of St James, Piccadilly.2

As a young boy Richard worked for his father and decided very early to become a sculptor. At 14 he was apprenticed

for seven years to (John) Charles (Felix) Rossi RA, who in 1812 sent him to the Royal Academy Schools to learn life

drawing, anatomy and sculpture.3 There he won two medals, one of which, in 1815, was the Silver Medal for the best

model from life.3,4 Meanwhile, under Rossi’s practical training, he was carving such routine commodities as chimney-

pieces and memorial tablets.3 Rossi was said to be more a mason than a sculptor, more a modeller than a carver. But

his bold and masculine style may have instilled confidence in his pupil.5

In 1813, when Richard was 18, Edward his father decided to set himself up in a country property, and he purchased

the house we know as Merton Cottage, in Church Path, Merton Park.6 It is a pity we cannot assume that Richard

made his home under his parents’ roof at Merton. He would more likely have been living with Rossi or in lodgings near

the Academy, but we can guess that he often visited Merton for home comforts – and did young men bring their

washing back to their mothers then? (Well, perhaps not.) Anyway, by 1819 Richard had finished his apprenticeship

and was in Dean Street, probably in his own studio.7

When the great Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822) visited London in 1815 Sir Thomas Lawrence

had introduced Richard to him and Canova had been impressed enough to promise the young man protection, patronage

and permission to work in his studio if he was able to come to Rome. That became Richard’s dream.7

After a spell in Paris in 1820 under the French sculptor Baron François-Joseph Bosio he went on to Rome in the

following year, armed with a letter to Canova from Lawrence, who by now was President of the Royal Academy. ‘As

I have known his family for many years, and I have the fullest confidence in his own blameless character, I take the

liberty of requesting you to allow him the view of your noble works, and to extend to him … the benefit of study in the

Academy …’, he wrote.8 In Canova’s studio Richard met John Gibson (1790-1866), who had already been studying

there for four years and would make a great name (and fortune) for himself. The two young men formed a friendship

that lasted until Richard’s death.9

In London Richard had studied the Parthenon marbles, as well as casts from the Vatican Museum.5 Canova too urged

his pupils to ‘study the Greeks’, to understand anatomy, and also to visit as often as possible the studio of Bertel

Thorvaldsen (?1768 – 1844), who was the other internationally renowned Neoclassical sculptor of the time. When

Canova died in 1822 Richard and Gibson were able to join Thorvaldsen’s studio.9

Richard James WyattFrom The Illustrated LondonNews 17 August 1850 p.162

The two young men took studios opposite each other in Via della Fontanella Barberini, breakfasted

together at dawn in a café, and worked all day – sometimes to midnight. Early in his career

Richard did all his work himself, but later he was able to afford assistants for the less specialised

procedures. He would first make a clay model, and then put it away for six weeks. If he was

then happy with it he would embark on the marble version. His figures were nearly always a

little under lifesize, and famously well finished. Final touches were carried out by candlelight.10

In 1822 Sir Jeffry Wyatville visited Rome with the Duke of Devonshire, for whom he did

much work at Chatsworth. The duke was taken to see Richard’s work and commissioned

from him a statue of the nymph Musidora, as described in the ‘Summer’ section of James

Thomson’s The Seasons.11

‘… this fairer nymph than ever blest Musidora by Richard

James Wyatt

Arcadian Stream, with timid Eye around

From The Art Journal vol.

The Banks surveying, strip’d her beauteous Limbs,

14 (1852) facing p.140

To taste the lucid Coolness of the Flood.’

The duke’s Musidora stands today in a niche in the room used as the Chatsworth shop.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 15

Richard Wyatt was described as ‘gentle and amiable’, ‘rather grave’, ‘very gentlemanlike’, and as uniting ‘superior

talent with great modesty’. He found his work popular and successful, particularly his female figures, and he was

admired as a portraitist. Sir Robert Peel and a Russian Grand Duke were only two of the distinguished British and

foreign figures who purchased from him.12

Meanwhile, back in Merton, his sister Caroline, older than him by two years, had met and marriedc.1822 a young man

of her own age called Isaac Cragg. He was a member of a large family who often visited their cousins, the brothers

Charles and Admiral Isaac Smith of Abbey Gate House, in what is now Merton High Street. Sadly, in 1823, Caroline

died in childbirth, and her infant son died with her. They were buried at Bunhill Fields. Charles Smith died in 1827 and

the admiral in July 1831, leaving as heir to the Merton Abbey estate their nephew, the widower Isaac Cragg, who

changed his name to Cragg Smith. However, at the end of the year he too died, aged only 38. He was buried at St

Mary, Merton, in a grave abutting the south-east corner of the church, and the remains of his wife and child were

removed from Bunhill Fields and interred in the same grave. Another cousin, Elizabeth Cook, widow of the explorer

Captain James Cook, older than any of them, outlived them all, and commissioned from Richard a relief monument to

commemorate her relatives, who were also his. It is dated 1832 and is now on the east wall of the north aisle of St

Mary’s. Rather cold-bloodedly, one might think, considering his own sister was concerned, he used the same design

a few years later for a monument in the church at Meopham, Kent.13

In 1841, after 20 years, Wyatt visited England again, and during his time here he was commissioned by Prince Albert

to make a piece to stand at the entrance to Queen Victoria’s apartments at Windsor. This was Penelope – an admired

figure, with a less successful dog (his later dogs were better). The Queen subsequently bought other works by Wyatt,

for Windsor and for Osborne House.14

This was his only return visit to England, but many commissions continued to come from this country, and over the

years several of his works were exhibited at the Royal Academy. His work was admired as simple, graceful and

natural; he did not attempt the grand or heroic. His images were inspired by classical mythology and by later literature.

Flora and Zephyr was commissioned in 1834 by Lord Wenlock, but was bought later in the same year, after

Wenlock’s death, by the owner of Nostell Priory.

Wyatt did not marry. He lived a retired life and worked extremely hard. Apart from slight lameness following a riding

accident10 he had good health, never being affected by the malaria endemic in Rome at that time. In the political upheaval

in 1848 he was much shaken when his studio was badly damaged by shellfire and he narrowly avoided injury. He moved

into Gibson’s studio, until finding himself a new one in Via dei Incurabile.15 He lived through the siege of Rome by the

French in 1849 and wrote to Gibson (who was away from Rome) to reassure him and to describe the situation.16

Wyatt died suddenly, of a stroke, in May 1850. Fifty people attended his funeral in Rome’s Protestant Cemetery.

Edward Wyatt, his father, had died 17 years earlier, and Merton Cottage passed to another son Henry John (1789

1862), an architect. Both men were active in local affairs – Edward serving as churchwarden in the early 1820s17 and

Henry as a trustee of the Rutlish Charity in the 1830s.18 Henry must have moved away later, for by 1853 Merton

Cottage was occupied by a new family, and the connection of the Wyatts with Merton had ended.

Judith Goodman

1.

This description of Wyatt is taken from The Illustrated London News 17 August 1850 p.162

2.

Baptism register of St James, Piccadilly, on microfilm at Westminster City Archives.

3 .

J M Robinson The Wyatts: an Architectural Dynasty (1979) OUP pp.160-163

4.

Illustrated London News op. cit.

5 .

R A Martin The Life and Work of Richard James Wyatt (1795-1850) Sculptor MA thesis

(unpublished) for University of Leeds p.18. Date of the thesis does not appear but appears to be

early 1970s. Two copies are available to the researcher: one is held by the Fine Art Department

of the University of Leeds, and one by the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds.

6 .

Information from the Merton manorial court rolls kindly provided by Peter Hopkins

7.

Martin p.19 8. Martin p.20 9. Martin p.21

10. Martin pp.23, 24 11. Martin pp.25, 26 12. Martin p.30

13. Other relief monuments by Wyatt are at Bessingby, Yorkshire; Poltimore, Devon; and Winwick,

Lancashire.

14. Martin pp.42, 50, 58 15. Martin pp.48-50

16. The letter can be found at www.royalacademy.org.uk

17. Merton Churchwardens’ Accounts. Surrey History Centre 3185/3/1

18. Merton Vestry Book. Surrey History Centre 3185/5/1

Other sources:

Gentleman’s Magazine (1844) Vol. II pp.71-72

Gentleman’s Magazine (1850) Vol. II p.99

D Linstrum Catalogue of the Drawings Collection of the RIBA: The Wyatt Family (1973)

M Trusted The Return of the Gods: Neoclassical Sculpture in Britain (2008) Tate Publishing, London

The monument on Wyatt’s grave in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome (Photo: Lionel Green)

Letters and contributions for the Bulletinshould be sent to the Hon. Editor.

The views expressed in this Bulletin are those of the contributors concerned and not necessarily

those of the Society or its Officers.

Printed by Peter Hopkins

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 166 – JUNE 2008 – PAGE 16

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY