Bulletin 173

March 2010 Bulletin 173

V-1s on Mitcham. Part 1: Memories D Haunton

Merton’s First Commuters G Wilson

The Priory Wall D Luff

and much more

VICE PRESIDENTS: Viscountess Hanworth, Eric Montague and William Rudd

BULLETIN NO. 173 CHAIR: Dr Tony Scott MARCH 2010

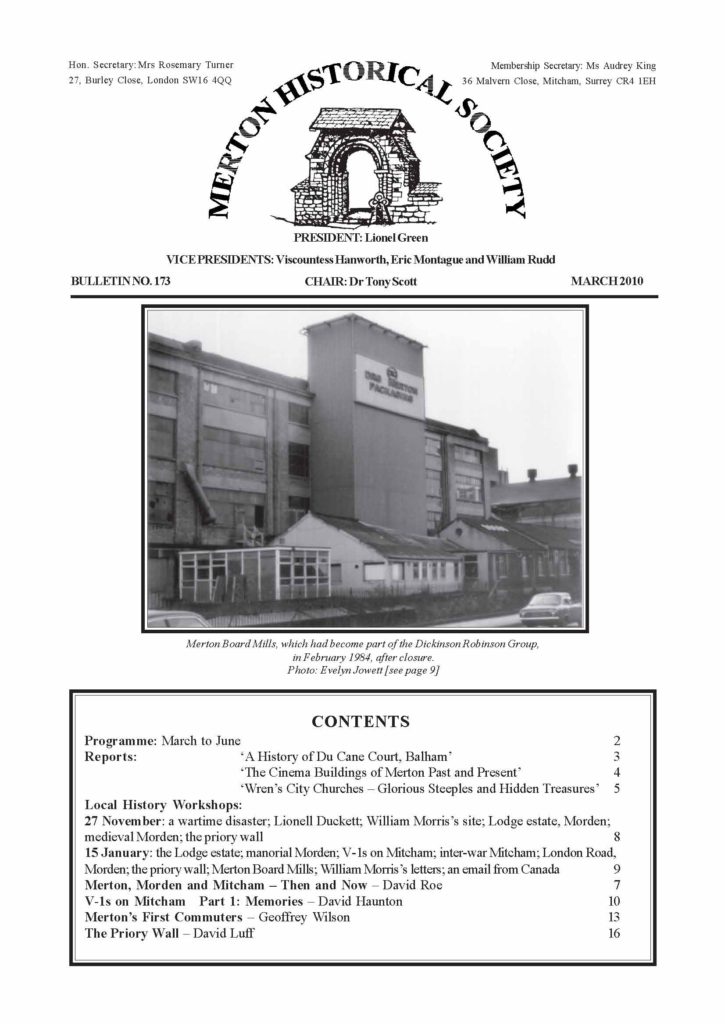

Merton Board Mills, which had become part of the Dickinson Robinson Group,

in February 1984, after closure.

Photo: Evelyn Jowett [see page 9]

CONTENTS

Programme: March to June 2

Reports: ‘A History of Du Cane Court, Balham’ 3

‘The Cinema Buildings of Merton Past and Present’ 4

‘Wren’s City Churches – Glorious Steeples and Hidden Treasures’ 5

Merton, Morden and Mitcham – Then and Now – David Roe 7

Local History Workshops:

27 November: a wartime disaster; Lionell Duckett; William Morris’s site; Lodge estate, Morden;

medieval Morden; the priory wall 8

15 January: the Lodge estate; manorial Morden; V-1s on Mitcham; inter-war Mitcham; London Road,

Morden; the priory wall; Merton Board Mills; William Morris’s letters; an email from Canada 9

V-1s on Mitcham Part 1: Memories – David Haunton 10

Merton’s First Commuters – Geoffrey Wilson 13

The Priory Wall – David Luff 16

Saturday 13 March 2.30pm St Theresa’s Church Hall

‘The St Helier Estate, a Home in the Country’

This illustrated talk by Margaret Thomas, Manager of Middleton Circle Library, Carshalton,

looks at the development of the Estate from its farmland origins onwards, and discusses the

preservation of oral memories of some of its residents.

The hall is behind the church, on the west side of Bishopsford Road, Morden,

about 200m north of Middleton Road. Parking at the hall or nearby.

Bus route 280 passes the door and route 80 is close by.

Saturday 10 April 2.30pm St Mary’s Church Hall, Merton Park

‘Literary Wimbledon’

An illustrated presentation by Michael Norman-Smith and colleagues from the Wimbledon Society.

The hall is in Church Path, Merton Park. If driving, access is from the Church Lane

end of the road, with parking at the hall or nearby. Bus routes 152, 163, 164

and K5 are close by, and the Merton Park Tramlink stop is ten minutes away.

Saturday 22 May Visit to Oxford and Waddesdon Manor

Pat and Ray Kilsby are again organising a coach trip for us. Information and booking details are

on the enclosed sheet.

Thursday 17 June 11am Guided visit to some Wren churches

Tony Tucker who gave us an excellent talk in January on Wren and his City churches, will lead

this visit to some of the City’s most interesting churches. £6 per head.

Visitors are welcome to attend our talks. Entry £2.

Holiday Offer

Pat and Ray Kilsby have a few places left on a tour organised for the WEA, 8-11 May staying at the

University of East Anglia, Norwich. Coach pick-up in Sutton.

GLIAS LECTURES

The Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society lectures are held in the Morris Lecture Theatre, Robin

Brook Centre, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London EC1 on the third Wednesday of the month at 6.30pm.

Visitors are welcome.

(Nearest stations: St Paul’s, Barbican, City Thameslink, Farringdon)

17 March Searching for Trevithick’s London Railway of 1808

21 April London’s Lea Valley: Britain’s Best Kept Secret

19 May Camden’s Railway Heritage

Further details 020 8692 8512

MEMORIES COLLECTED BY FRANCIS FRITH WEBSITE

Sheila Fairbank has told us about the local reminiscences published on the Frith website, sparked by local

photographs in the Francis Frith collection. Visit www.francisfrith.com to view the photographs, read their

reminiscences and add your own. And why not copy your reminiscences to mhs@mertonhistoricalsociety so

that we can include them in a future Bulletin!

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 2

‘A HISTORY OF DU CANE COURT: LAND, ARCHITECTURE, PEOPLE

AND POLITICS’

Gregory Vincent, himself a resident of Du Cane Court and a member of the Balham Society, gave this talk after

our AGM on 7 November at Raynes Park Library Hall. It should have been an illustrated one, but Mr Vincent

made the disastrous error of not checking beforehand how to use the projector he brought with him, with the

laptop provided by the library. Efforts by our members and by one of the library staff proved fruitless, and finally

the speaker went ahead without his images. We apologise to all who were there, for this frustrating experience.

The Du Cane (originally du Quesne) family were Huguenots from Flanders who arrived in this country in the

1570s, bringing skills but few possessions with them. However, in time they prospered, and one branch came to

be landowners on a large scale, including a big slice of Balham. Their name lingered on into the 20th century.

By the 1930s Balham, with both Underground and mainline rail services, was a convenient place to live for

people who worked in central London. In 1935 Du Cane Court Ltd was set up with £20,000 nominal capital, and

the development began of the site on the west side of the High Road where had stood the large residence of a

popular, and rich, doctor. Building took place,

in two stages, from 1936 to 1938, with the

architect being the not very well-known George

Kay Green. It is a concrete-clad pre-stressed

steel structure, subdivided into blocks. With its

gardens (originally in Japanese style) it occupies

4.5 acres (1.8h), is large enough to be allocated

more than one postcode, and contains perhaps

two miles of corridors. It has seven floors,

including lower/upper ground floor and a couple

of penthouses. The exterior features fine

brickwork, and within there is much marble and

terrazzo. There are about 1200 habitable rooms,

and it is, or was, the largest privately owned

block of flats under a single roof in Europe.

With its striking art deco lines it has often been

used for filming (Poirot, The Bill).

Flats at the front had gas and electricity, but those at the back had electricity only. The windows are metal-

framed. Sinks were of porcelain and draining boards of teak. Every flat had a built-in clock and radio, central

heating, electric fires, and plenty of built-in cupboards.

At first there were games rooms, with billiards and table tennis, two bars, a restaurant, and roof gardens,

though a projected squash court and a crèche did not materialise. The porters wore top hat and morning-coat,

and visitors were escorted by pageboys. The address was recognised as a stylish place to live, with the rules

for accepting a new resident sometimes being seen as discriminatory.

The flats became worryingly quiet with the outbreak of war in 1939, and a number of junior Foreign Office

staff were moved in, at cut rates, and also Polish refugees. Firewatchers used the roof and no doubt saw the

bombing of the Underground station close by in October 1940 [see page 8], but Du Cane Court itself was never

bombed. Some wild theories circulated. Did Hitler have his eye on it for an HQ? Were there spies among the

residents? It is perhaps more likely that the German planes refrained from attacking it because it was such a

useful landmark.

Like many other large blocks of flats Du Cane Court has had to weather problems from time to time, problems

of ownership, management, and maintenance. It was popular again after the war, but suffered a financial bad

patch in 1961. From the 1960s people could buy their flats, and a residents’ association was set up in the 1970s.

There have been some well-known people as residents and visitors, with show business a strong element, such as

comedians Tommy Trinder and Richard Hearne (‘Mr Pastry’), bandleader Harry Roy, singer and broadcaster Anona

Winn, actors Richard Todd, Margaret Rutherford and Elizabeth Sellars. And cricketer Andrew Sandham lived there

for many years – it is convenient for the Oval. Today comedian Arthur Smith makes Du Cane Court his home.

Despite the lack of illustrations this was an interesting and often amusing talk.

Gregory Vincent’s book, with the same title, is published by the Woodbine Press and sells for £11.99.

Judith Goodman

(Part of) Du Cane Court, Balham High Road

Photo: JG Jan 2010

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 3

‘THE CINEMA BUILDINGS OF MERTON PAST AND PRESENT’

‘THE CINEMA BUILDINGS OF MERTON PAST AND PRESENT’

One of the earliest known locations for film showing was Mitcham Fair, where the ‘Lyceum Theatre of Pictures

and Varieties’ consisted of a white screen and benches inside a tent. This continued in operation up to about

1914. Buildings such as the Vestry Hall also showed films from time to time, but with the advent of the 1909

Cinematograph Act, requiring statutory licensing of premises and fire regulations for showing the highly inflammable

nitrate film then used, a new generation of purpose-built cinemas came into being. One of the earliest such was

the Abbey Picture Theatre in Merton itself, on the corner of Mill Road and Merton High Street. This existed

from c.1909 to 1929, when the expense of converting it for ‘talkies’ caused it to close.

In Mitcham the Majestic, on the corner of Fair Green, opened in 1933, seating 1500 and including a balcony

and a then-obligatory Compton organ, complete with constantly changing coloured light panels, rising on a lift

from the orchestra pit. It became part of the ABC chain, but closed in 1961, the building later being used for

Bingo, and then for Caesar’s Night Club.

In Morden was the Morden Cinema,

opposite the Underground station. It opened

in 1932 and was one of the first Art Deco

cinemas in London, designed by J Leslie

Beard. This seated 1600, had the inevitable

Compton organ, and in 1937 was renamed

the Odeon. In 1973 it was closed because

of falling audiences, and later was used by

B&Q, before being demolished and

replaced by Iceland and other businesses.

In Raynes Park we had the Rialto Cinema

in Pepys Road, opening in 1921, with 550

seats. It was rebuilt in 1933 with 750 seats,

but closed in 1978.

In St Helier the Gaumont in Bishopsford Road, designed by Harry Weston, opened in 1937 with an

enormous 2000-seat auditorium to serve the Estate. Like many cinemas of the time it included a café/

restaurant. The interior was designed by the well-known firm of Mollo & Egan in Art Deco style. It closed

in 1961, becoming a Top Rank Bingo Club and then the Mecca Social Club. It is listed Grade II by English

Heritage.

Wimbledon boasted at least four cinemas at one time. The earliest was the Apollo Theatre in the Broadway.

It seems to have been formed by combining two adjacent shops, and was opened in 1912 with 250 seats. It later

became the Prince’s Cinema, but closed in 1937. The building is now the Confucius Chinese restaurant, but

traces of the original advertising can be seen on the side walls.

The Nelson Hall Picture Palace in Merton High Street, between Hardy and Hamilton Roads, had a brief

existence from c.1913 to c.1916.

Further up the Broadway, was the Elite Super Picture Palace, designed by J Adamson and opened in 1920 with

about 1000 seats. In 1926 it acquired one of the first Christie organs built by the well-known church organ

builders Hill, Norman & Beard. In 1928 it was enlarged to 1250 seats by adding a balcony above the stalls, and

in 1935 it was acquired by the ABC cinema chain. In 1964, in an attempt to attract more people back to the

cinema, it was completely refurbished, including a new frontage, with the seating reduced to 1000 to increase

comfort. There was a Gala Opening Night, with Cliff Richard starring in Wonderful Life. However, audiences

continued to drift away. It closed its doors in 1983 and despite a local campaign was demolished in 1985 and

replaced by offices, currently the CWU headquarters.

Then there was the King’s Palace in the Broadway, opposite Kings Road, which opened in 1910 (almost the

same week as the Theatre). It seated 350 initially, but was enlarged to seat 800 in 1950 by building a new

auditorium behind the existing one. It had a full stage and dressing-rooms, and originally put on both variety

shows and films. It closed in 1955, becoming a roller-skating rink before demolition reduced it to a car park for

the Theatre.

Morden Cinema in 1933, reproduced by courtesy of Merton Library &

Heritage Service

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 4

The fifth cinema was in Worple Road, and was known first as the Savoy and later the New Queen’s Cinema,

seating 350 at first. It was redeveloped as an Odeon in 1936 with 1500 seats, at a cost of £30,000. Its Art Deco

interior had an Egyptian theme. Unusually there was no organ. When it closed in 1960 the name was transferred

to the Gaumont (see below).

The fifth cinema was in Worple Road, and was known first as the Savoy and later the New Queen’s Cinema,

seating 350 at first. It was redeveloped as an Odeon in 1936 with 1500 seats, at a cost of £30,000. Its Art Deco

interior had an Egyptian theme. Unusually there was no organ. When it closed in 1960 the name was transferred

to the Gaumont (see below).

Almost next door we now have the HMV Curzon cinema with three small viewing areas of 70-100 seats, again

on the first floor. The screens are designed to be 3-D capable.

In the discussion afterwards reminiscences were shared, of the smoke-filled atmosphere, the usherettes, ice-

creams, Saturday children’s clubs, and double seats for couples at the back of the stalls. Mention was also

made of the Shannon Corner Odeon, just within the Borough. Reputedly this was the only cinema to be camouflaged

during the war, because of its proximity to the Decca Radio factory.

The talk was enjoyed by 37 members and guests, and Richard Norman was given a well-deserved ovation.

Desmond Bazley

‘WREN’S CITY CHURCHES – GLORIOUS STEEPLES AND HIDDEN

TREASURES ‘

At Raynes Park Library Hall, on 9 January, twenty-one hardy members braved ice and snow to enjoy a

splendidly illustrated talk enthusiastically given by Tony Tucker, qualified City of London guide, and committee

member of the Friends of City Churches.

Tony started with a swift survey of the life and non-architectural achievements of Sir Christopher Wren (16321723).

He was born in East Knoyle, Wiltshire, but his father was soon appointed Dean of Windsor, and Christopher

grew up in the company of princes, making him a decided royalist. He attended Wadham College, Oxford

(taking his MA in 1653), where the scientific circle of the warden John Wilkins included William Petty, Robert

Boyle, and John Evelyn, not to mention Hooke, Locke and Newton.

In 1657 Wren became Professor of Astronomy at Gresham College, London, in 1661 Savilian Professor of

Astronomy at Oxford, and in 1660 was a founder member of the Royal Society (of which he was President

1680-1682). His many interests included anatomy and medicine, sundials, submarine navigation, the problem of

determining longitude, telescopes, microscopy, the mathematics of cycloid curves, and the lunar influence on

atmospheric pressure. He made a globe of the Moon and presented it to Charles II, who displayed it proudly,

was an MP (three times), a director of three companies, and twice married (to Faith for six years and then to

Jane for only three). He was publicly praised as a prodigy and genius before he was 30, but was good-natured,

apparently never having a serious argument with anyone, even the notoriously combative Hooke.

Then in 1666 the Great Fire destroyed some two thirds of the City, including 86 churches, and Wren began his

architectural career. He built or rebuilt 50 City churches, as well as the circular Sheldonian Theatre, Trinity

College library and Tom Tower (all in Oxford), the Monument (with Hooke), the Royal Observatory at Greenwich,

the Royal Hospitals at Chelsea and Greenwich, Hampton Court, Kensington Palace … and St Paul’s cathedral.

Among others.

But our talk centred on the surviving City churches. Tony Tucker introduced us to 17 of them, all different.

Wren had no training as an architect: his designs were informed by his mathematical studies, drawings of Greek

and Roman remains, and designs of his own time (particularly those of Francesco Borromini), though he would

cheerfully turn his hand to traditional Gothic if the parish insisted. In general the churches were hidden away

down side streets or alleys, and the sites could be small (St Mary Abchurch measures only 19m x18m inside)

and irregular. There is no repetition of design – Greek cross or rectangular plan; barrel vault, flat ceiling or

dome; coffering or fan-vaulting; one aisle or two or none; gallery or no gallery.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 5

The steeples seem to have been Wren’s speciality, and again vary tremendously. For example, the simple lead-

covered obelisk of St Margaret Lothbury, the three-stage affair at St James Garlickhythe, the octagonal one

with single columns at St Michael Paternoster Royal, the classically modelled one with 12 columns in a circle

supporting 12 in a square at St Mary le Bow, the alternate convex and concave stages (Borromini influence), at

St Vedast alias Foster, the off-centre one at St Lawrence Jewry (due to the odd shape of the site), and the five-

tier wedding cake at St Bride Fleet Street, which imitates no cake but is the prototype upon which wedding

cakes were later modelled.

The steeples seem to have been Wren’s speciality, and again vary tremendously. For example, the simple lead-

covered obelisk of St Margaret Lothbury, the three-stage affair at St James Garlickhythe, the octagonal one

with single columns at St Michael Paternoster Royal, the classically modelled one with 12 columns in a circle

supporting 12 in a square at St Mary le Bow, the alternate convex and concave stages (Borromini influence), at

St Vedast alias Foster, the off-centre one at St Lawrence Jewry (due to the odd shape of the site), and the five-

tier wedding cake at St Bride Fleet Street, which imitates no cake but is the prototype upon which wedding

cakes were later modelled.

All this work was carried out by English artisans – the same names recur, for wood carvers (Grinling Gibbons,

William Newman, William Grey and William Emmett), stone workers (the three Strong brothers, William Kempster

and Gibbons again) and plasterer Henry Doogood.

So, go and admire the riot of carving on the reredos at little St Martin Ludgate, the carved pulpit, tester and

organ at St Magnus the Martyr, the unique carved churchwardens’ pews at St Margaret Pattens, the hidden

garden of St Vedast, the plaster fan-vaulting at St Mary Aldermary, the Gibbons reredos and the painted dome

at St Mary Abchurch, the coffered central dome at St Stephen Walbrook (the first dome to be constructed in

England) and much more. Of all the beauties we were shown my favourite is St Dunstan-in-the-East, bombed

during the war, so that only the walls and tower remain. The interior is a garden, reflecting the plan of the

church, with pergolas where the nave pillars stood, little box hedges defining the pews, and rose bushes for the

congregation. And, soaring above, Wren’s astonishing steeple, with its spire and lantern balanced on four flying

buttresses and daylight.

David Haunton

St Dunstan in the East

from Tony Tucker’s The Visitor’s Guide to the City of London Churches

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 6

MERTON, MORDEN AND MITCHAM: THEN AND NOW

.The Society is grateful to Mr Mick Taylor for sending us photographs he has taken in the last two years around

Merton, Morden and Mitcham. Many of these will go to the Society’s photographic record project, and Mr

Taylor has been invited to make further contributions. He is a resident of Morden, a keen photographer, and a

supporter of Wandle Industrial Museum.

He has chosen scenes to photograph that are at the same locations shown in old photographs in published

books. One example is given here: the parade of shops in the Kingston Road at the junction with Bushey Road,

opposite the Emma Hamilton. The old photograph, from the Merton Heritage & Local Studies Centre collection,

was taken c.1930 and reproduced in Merton & Morden: a Pictorial History by Judith Goodman. Mick

Taylor’s photograph was taken in October 2008. His caption says: ‘Whilst the buildings remain unchanged the

road junction has been completely developed to reflect the increase in traffic on this busy road. The phone box

has disappeared’. Most of the shops have changed use since 1930; one exception is the wine merchants, which

housed Stowell’s off licence in 1930. In the book it says that in 1930 ‘Eyles & Son, Grocers, later became a sub-

post office as well’. In the 2008 photograph this shop, ‘Chase Post Office’, is sadly closed, with the ‘Post’ in its

name blacked out.

This comparison of ‘then’ and ‘now’ shows how a shopping parade in 1930 could have a pleasant appearance,

with its clean architectural lines and elegant street furniture (phone box, signpost and lamppost). However the

appearance in 2008 has changed for the worse, with recent additions above shop level (roof extensions, alarms,

notice boards, and satellite dishes), non-matching shop fronts, and a proliferation of street furniture (traffic

lights, bollards, railings, tall lighting etc), with no harmony of design.

David Roe

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 7

LOCAL HISTORY WORKSHOPS

Friday 27 November Seven present – Cyril Maidment in the chair

.

……….David Haunton had been very busy since the last workshop. He began with the tragedy of 14 October

1940, when a German bomb fell on Balham Underground station. This event figures in the memoirs of ex-

Mordonian Ronald Read, to be published shortly by the Society, and was also touched on by our lecturer on

Du Cane Court [see page 3], and casualty numbers vary widely in different accounts. David found that it

was a 1400kg semi armour-piercing bomb that fell just after 8pm, close to the station, producing a wide and

deep crater. A double-deck bus was unable to stop in time and ran into the crater, producing the famous

image photographed the next day. The blast, which penetrated to the northbound platform area, also fractured

a water main, and, as Balham is at the lowest point on the Northern Line, the water had nowhere else to go.

It soon filled the northbound platform area, swept through the cross-passages and filled the southbound

area. As one of the deep Underground stations where local people were allowed to shelter overnight,

Balham’s official capacity was 600 persons (allowed in by ticket). More than 500 seem to have been in the

station at the time, but no formal record could allow for passengers who left trains and merely stayed on the

platforms. Over 400 people escaped from the station, of whom more than 70 were injured. Deaths were

mostly by drowning. The last body was not recovered until January 1941. The number of deaths usually

quoted, for example on the commemorative plaque in the station, is 64. However the Commonwealth War

Graves Commission recorded 65 names of civilians; presumably this includes a casualty who later died in

hospital. Three Underground employees also died, but were not recorded by the CWGC for some reason.

So the total known death toll is 68 persons. (A boat was sent from Clapham South station, but was unable to

get through to render assistance. David wondered, how many Underground stations have a boat handy?)

He quoted from the Merton & Morden UDC Minutes of 5 June 1954: ‘… [The] last of 26 miles of bunks

installed in Tube shelters was removed at South Wimbledon station on 31 May; at this station over 600,000

people have sought protection from air raids during the past 4½ years.’

One-time Mordonian Ronald Read, mentioned above, worked briefly as a sheet metalworker with a short-

lived company called Ranelagh (?Ranalah) on the Lombard Road estate, which David was investigating.

He had also been pursuing Lionell Duckett, co-purchaser in 1553 with Edward Whitchurch of the Morden

estate. Duckett (c.1510-1587) was a member of the Mercers Company, of which he was four times master,

and was Lord Mayor in 1572/3, when he was knighted. A very rich man, he scooped up a number of former

monastic and chantry lands in Surrey and elsewhere, though he did not hang on to Morden for long.

.

……….Judith Goodman had been re-reading three contemporary accounts of visits to William Morris’s works at

Merton Abbey. Surprisingly perhaps, it was one that appeared in a society ladies’ magazine which gave the

most detailed information about techniques, the workforce, and the buildings.

.

A friend had obtained for Rosemary Turner photocopies of the entries relating to Morden’s Lodge estate

in the 1910 Valuation records at The National Archives. Others present had never heard of this survey, but

it sounds a wonderful source for early 20th-century history. The Valuation used 25-inch OS maps and took

place in 1910-12. Four whole pages, including a plan, are devoted to the Lodge and its ancillary outbuildings

and cottages, full of detail – such as building materials, and numbers, sizes, uses and condition of rooms.

.

……….Peter Hopkins reported that his work on medieval Morden was at a key stage. All the translations had

been completed, and checked. He had obtained permission from Westminster Abbey, the Society of

Antiquaries, and the Bodleian Library to put the material on our website. He had brought along a script he

has written for the website, in which he lists and describes documents relating to medieval Morden – court

rolls, tax receipts, leases, a custumal, and so on.

He singled out one document (TNA SC

8/188/9369) in medieval French and

partly faded, which related to the

Sparrowfield dispute with Cheam, as

proving particularly tricky to decipher

and translate.

.

……….Cyril Maidment is concerned about the future of historic remains in the Borough. Fragments of the priory

wall, for instance, in back gardens at Windsor Avenue. They may well be disintegrating under their cloak of

ivy, and it is only too possible that the householders are not aware of their significance.

Judith Goodman

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 8

Friday 15 January 2010 – nine present – Judy Goodman in the chair

.

Friday 15 January 2010 – nine present – Judy Goodman in the chair

Rosemary Turner continues her research into The Lodge estate, Morden. The 1910 Valuation document

has about 500 entries for Morden, covering 2000 pages, so a copy would be expensive, and laborious, to

obtain. The 1911 Valuation map shows two areas previously unknown as part of the estate, one of them a

market garden, shown in much detail.

.

……….Peter Hopkins has been busy loading copies of some 300 documents onto the website. Under ‘Projects’,

we now have available translations of all known manorial documents relating to Morden before 1732, as

well as images of those documents held by Westminster Abbey Archive, the Society of Antiquaries, the

Bodleian Library and Surrey History Centre. (Permission to reproduce images of documents in the British

Library and Cambridge University Library has been received since the Workshop.) Peter would welcome

feedback from website connoisseurs.

.

……….David Haunton

noted a dig in

Ravensbury Park

(reported in London

Archaeologist) that

found no Saxons, but

environmental

evidence for the last

11,000 years.

He discussed the

problems of

identifying the V-1s

that fell on Mitcham,

reconciling the

records held in The

National Archives

with Borough of

Mitcham Incident

Map held at Merton Heritage and Local Studies Centre at Morden Library. [see page 10]

.

……….Keith Penny is interested in the onset of urbanisation in Mitcham, especially in the Streatham Vale area.

He asked for help in finding possible sources of information about Mitcham incomers in 1925-1939, particularly

where they came from and why they came, but also their occupations. Most seem to have been owner-

occupiers, and so relatively well off.

.

……….Bill Rudd showed us photos of shops in London Road, Morden, that have now gone (many were shoe

shops, such as Lilley& Skinner, Bata and Freeman, Hardy & Willis). He has detected some hopeful signs of

recent economic recovery in the area.

.

……….David Luff discussed further the date of destruction and the identity of the destroyers of part of the Priory

walls [see Bulletin172]. He showed us a portfolio of his photos of different parts of the various walls, taken

at various dates, and maintained that the wall within Liberty’s that ‘disappeared’ looked nothing like the

precinct wall in, for instance, Station Road. [see page 16]

.

……….Cyril Maidment was much interested in David’s conclusions. He then showed us Evelyn Jowett’s photos

of the Board Mills factory after its closure, before redevelopment of the site for Sainsbury’s. [see page 1]

He had drawn up several displays to show the direction of view of each photo.

Cyril had also discovered a photo (taken by Norman Plastow) of the Wimbledon Society Museum Committee

in 1979 (Wim. Soc. P1878) which shows the elusive Miss Jowett.

.

……….Judy Goodman has been studying the published volumes of William Morris’s letters, and finding a surprising

amount of local information.

She, and others, are dealing with an email to our website from a lady in Canada enquiring about Littler’s

Cottages in Phipps Bridge Road, whence her grandmother Gwendolyn Gladys West emigrated, and offering

a copy of an etching or drawing of the said cottages c.1900. [More about this in the June issue – Ed.]

David Haunton

Next workshops: Fridays 5 March, 16 April, 4 June at 2.30 at Wandle Industrial Museum. All are welcome.

V-1 in flight from Norman Longmate The Doodlebugs

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 9

DAVID HAUNTON has been exploring

DAVID HAUNTON has been exploring

The V-1 itself was a small aircraft, constructed almost entirely from thin sheet steel, and powered by a primitive

jet engine (technically a ‘pulsating athodyd’) which produced a characteristic stuttering roar when running.

Guidance mechanisms kept it level, on a straight course, and at a constant altitude. The airflow over its nose

turned a small windmill. After this had rotated a pre-set number of times the fuel line to the engine was cut and

the missile fell to earth, where its 850kg warhead exploded.

Because of the V-1’s speed of between 300 and 400mph, there was usually less than ten minutes between the

sirens sounding and the arrival of the missile. When the rattle of the engine stopped there would be ten or 12

seconds of silent and anxious waiting time before the explosion. Occasionally a V-1 failed to dive at this point,

and continued to glide, with a sound recollected by an anonymous Mitcham optician as a ‘soft rustling … like a

small sailing boat, when the wind was making the sails flutter’.1

Forty-five of these missiles fell on the Borough of Mitcham between June 1944 and January 1945. Here are

three stories from people who experienced them.

Alan Simpson, Friday 23 June 1944

The warning siren went at 07:56 and the seventh V-1 to fall on Mitcham in less than a week scored a direct hit

on 32 Greenwood Road at 08:07. The damage report is unusually explicit, so we know that the explosion

completely demolished five houses (nos. 32-40) and so seriously damaged another four (24-30) that they would

have to be pulled down and rebuilt. A further three houses (44-48), though having more than 50% of their

external walls still standing, and thus formally being classed as ‘repairable’, were adjudged too dangerous to

leave unattended, and were also written off to be demolished. Despite this widespread destruction, only six

people lost their lives (one each from 31, 36, 37, 39, 41 and 43). All were recorded as having died in their own

homes, which is possible, but perhaps some had gone

to the brick-built public shelter in the street, only 35ft

(11m) from no.32. This was described as having

suffered ‘severe fractures to walls and central bay

collapsed’.

The all-clear was sounded at 09:02, and Elsie Simpson

and her one-year-old son Alan emerged from their

Morrison shelter (husband Jack was at work). Their

home at 51 Greenwood Road, newly built in 1938, had

suffered what is usually described as ‘some blast

damage’ to doors, windows, ceilings and tiles. The front

door had been blown off its hinges and had arrived at

the top of the stairs. The lid of the baby grand piano

had been slightly lifted by the blast, and its interior had

collected a lot of window glass – so much so that

decades later Mrs Simpson was still finding odd shards

to remind her.

Some hours later the same day, young Alan was

entrusted to Vi Rolf, a family friend, while clearing up

was in progress. On the way to her house in New Barns

Avenue the warning siren sounded again. Vi was

halfway between two public shelters in Sherwood Park

Alan’s travels, on his ID card

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 10

The crypt of the Church of the Ascension as an air raid shelter

Crown copyright: The National Archives ref. HO 207/772

The crypt of the Church of the Ascension as an air raid shelter

Crown copyright: The National Archives ref. HO 207/772

approach. Luckily she chose the one which was

going to become the Church of the Ascension. The

eighth V-1 to fall on Mitcham landed in the front

garden of 142 Sherwood Park Road at 17:05. This

was unusually destructive. It demolished twice as

many houses as the Greenwood Road bomb, while

heavy blast damage was noted up to 100 yards (90m)

away, and lighter blast damage up to 600 yards

(550m) distant. A surface shelter of 14-inch (35cm)

solid brick set in cement mortar, with a 6-inch (15cm)

reinforced concrete roof, was demolished, some 50ft

(15m) from the explosion (this is the one Vi Rolf did

not choose). Of the seven people who were killed, one had been in this shelter, the others in their homes or in

the street.

The Simpsons stayed with Vi Rolf that night. The next morning Jack took Elsie and Alan to stay with family in

relatively safe Edgware in north London. After three weeks they were evacuated to Wales. Jack himself

moved in with his parents in Wandsworth, from where he could reach his job in Croydon by the 630 trolleybus.

He worked at repairing the family home at weekends, and was toiling there when on 5 August he witnessed yet

another V-1 falling locally, in Beverley Road. This caused further damage to no.51, and Alan remembers his

father sadly commenting ‘there was much to do again’. However, in May 1945 the Simpsons returned to

Greenwood Road, and lived there for the rest of their lives, Jack dying in 1993, Elsie in 2002.2

As an aside here we note that the crypt of the Church of the Ascension had been built in 1938-9, but that all

civilian building had been peremptorily halted at the outbreak of war in September 1939. By the summer of 1940

Mitcham Borough Council had provided a large number of public shelters, to house some 6000 people. They

were already exploring the need for more, and authorised the construction of a further 18 purpose-built shelters,

each to hold 50 people. The already-built church crypt was adapted as a shelter by being given a 6-inch (15cm)

concrete floor and a 6-inch reinforced concrete roof, covered by three feet of earth. It would hold 130 people

in eight compartments. By October 1940 it was understood that Rev. Shute was to supervise the shelter, with

volunteers from the members of his church. A note states that ‘it is intended that the church be built in the

future’; it duly rose post-war and was consecrated in 1953.

Cyril Maidment, Friday 14 July 1944

Young Cyril (aged 10) was in Christchurch Road, waiting with his Mum for the 152 bus (they were going to the

Vestry Hall to get new ration books) when they heard the typical engine noise of a V-1. And then it stopped.

They ran to take refuge in Colliers Wood Underground station, which they reached just before the bomb went

off. Cyril was at the top of the escalator, and Mum close behind, when there was a ‘giant bang’. They waited

a few minutes, and then went outside, to see lots of broken glass everywhere, mostly from shattered shop-

fronts. Cyril cannot recall hearing any warning siren.

The V-1 had fallen in Christchurch Close (previously Abbey Close), beside the vicarage and about 100 yards

(90m) from Christchurch Road, leaving a crater 20ft (6m) across and 5ft (1.5m) deep ‘in clay soil’. Fortunately

no one was killed, but the blast caused extensive damage over a wide area. A brick-built public shelter only 45ft

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 11

(13.5m) from the explosion was ‘fractured but otherwise intact’. The Southern Cylinder Services factory in

Fortescue Road was put out of commission, the church was badly damaged (repairs were not completed until

1953) and the vicarage, the church hall and six houses were destroyed.

(13.5m) from the explosion was ‘fractured but otherwise intact’. The Southern Cylinder Services factory in

Fortescue Road was put out of commission, the church was badly damaged (repairs were not completed until

1953) and the vicarage, the church hall and six houses were destroyed.

One of those six houses was 29 Fortescue Road, owned outright by the Sweet family, the mortgage having been

paid off only two or three years earlier. This was a substantial terrace house, with three bedrooms upstairs,

front and rear reception rooms, and a ‘middle’ room downstairs which was officially a breakfast room, but in

use as a bedroom. Victor Sweet, carpenter and joiner, and Sophie his wife were both in their fifties, while young

Bert was still at school (aged 13), and his three older brothers were all away in the services.

When the siren sounded at 09:47, Mum was out shopping. Bert was playing in the street, so he went straight

home, and into the Morrison shelter indoors. (The family had an Anderson shelter in the garden, but this was

hardly ever used, because it got very damp. The excavation had acted as a sump, and the dampness was not

cured even by the installation of a concrete floor.) After a couple of minutes, officially at 09:49, there was the

‘biggest bang you ever heard in your life’. The ceilings came down; doors, windows and the back wall blew out,

and the water pipe from the mains supply was broken. The house was uninhabitable.

Bert emerged from the debris, and

followed family instructions to go to

a neighbour some houses away, in

the same road. Only a few minutes

later he clearly heard another V-1

fly over. (This one probably fell on

Wandsworth.) After the all-clear

sounded at 10:16 Bert was collected

by an ARP rescue party and taken,

in official transport, a ‘not very

comfortable’ converted van, to the

Rest Centre in Mitcham Baths on

London Road. Mum joined him later,

and phoned Dad at his work. He

arrived after a while, having left work immediately on receiving the

news, and the whole family stayed for a single night in the Rest Centre. Accommodation was minimal – all

bombed-out persons were given space on the boarded-over swimming pool, and while Bert remembers blankets,

he is not sure about mattresses. It appears that some 50 or 60 people spent that particular night at the Centre,

but, as the space was not partitioned off in any way, household groups dotted themselves around the perimeter

of the bath. Bert particularly recalls the continual creaking of the boards during the night, as people moved

around.

Mitcham Baths (1932) with water rather than planks from Mitcham by Nick Harris (Nonsuch 2006)

The family was then billeted in a requisitioned house at 12(?) Birdhurst Road until the end of the war. This

house was shared with at least one lodger, a gentleman who worked at one of the firms near Shannon Corner,

so the Sweet family had only the use of the downstairs rooms. Quite a lot of their furniture was salvaged by the

Civil Defence workers, ‘scratched of course’, but only a few pieces (such as beds, the dining-room table and a

‘Utility’ chest of drawers) could fit into their new abode. The rest was stored by the Council ‘for the duration’.

A surprising quantity of clothing was also rescued, since it had been in wardrobes, which protected it to some

extent from the effects of the explosion.

With the end of the war, the owners of no.12 returned, and the Sweet family moved round the corner (literally)

to 19 Warren Road. Here the Council delivered all the remaining salvaged furniture from their home, some of

it, like the upright piano, very much the worse for wear. Again the house was shared, this time with an elderly

lady who occupied an upstairs room. When two brothers returned from the Services the house was too crowded

for them to stay, so one took digs in Balham and the other in Streatham. The Ministry of Supply compensation

for war damage to 29 Fortescue Road amounted to very little more than the value of the land, so the family

were unable to buy a house post-war, and Bert’s parents lived in rented accommodation for the rest of their

lives.

1. N Longmate The Doodlebugs (1981) Hutchinson, London p.208

2. Alan left Mitcham c.1978 and now lives in Halifax; it was his enquiry that started this whole investigation.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 12

GEOFFREY WILSON speculates about

MERTON’S FIRST COMMUTERS

GEOFFREY WILSON speculates about

MERTON’S FIRST COMMUTERS

1 Eric Montague includes much fascinating

detail about the Holden family and its short-stage coach interests from the 1830s. Mr Montague’s account gives

various details about the remarkably lavish service of such coaches between Mitcham and central London,

mainly for commuters to City offices. In fact the Holden brothers also operated a short-stage service between

Morden, Merton and central London, consisting of separate coaches running to Somerset House, to Gracechurch

Street and to Fleet Street. Barker and Robbins’s table and map of short-stage routes in 18252 show routes to

London from Croydon and Merstham, from Tooting, Mitcham and Carshalton, and from Wimbledon via

Wandsworth. So we can assume that the service from Morden was post-1825. However, statistics show that it

was operating by 1830.

These though were by no means the first ‘commuter’ services in our area, for John Feltham in his The Picture

of London for 18053 tells us that Mitcham was then served by stage coaches from Charing Cross, Gracechurch

Street, Fleet Street and Water Lane. These were afternoon services, except for an 8am coach from Gracechurch

Street, and hourly coaches from Fleet Street. Merton had a single 3pm service from Gracechurch Street.

(Morden is not mentioned.) Feltham takes care to state that ‘The stages generally set out a quarter of an hour

later than the hours here stated'(!). It can be assumed that all these journeys ‘out’ were matched by journeys

‘in’.

Even in 1831 the population of Mitcham was only 4387, and that of Merton 1447. Morden was still so small that

it can hardly have furnished any appreciable patronage. It is remarkable that with only a modest proportion of

this population to draw upon these early transport businesses managed to attract a sizeable and dependable

clientele.

Nevertheless by 1840 short-stage coaches and the omnibuses which were by then superseding them were

offering a surprising range of services from the outer suburbs to central London. South of the river alone, in

addition to the three from Mitcham, Merton and Morden, there were services from Richmond, Putney, Wimbledon,

Streatham and Croydon (already the largest town in Surrey). Remarkably, the Wimbledon service already ran

ten coaches a day by 1830, and five years earlier Clapham was served by no fewer than 29 coaches daily.

To compensate for any shortfall of passengers the operators were entitled to pick up en route, but there were

also services which began their journeys nearer to town. Regular patronage from Tooting and Clapham in

particular helped to make the services more profitable. Who were these regular patrons who lived so far from

their occupations?

There appears to be no record of whether a vehicle which had set down passengers at its London destination

immediately returned to its suburban base, picking up any passengers offering themselves en route, before

returning to central London to collect its home-going regulars.

I suspect that those who used the services were middle-class clerks, merchants and officials, who did not need

to arrive in London at the crack of dawn. In fact some did not need to reach their counting house or office

before 10am.

The services to Gracechurch Street would have catered for City clerks and perhaps middle managers. Fleet

Street suggests lawyers’ clerks and printers, while Somerset House would have been the destination for

government clerks. As well as the services from south of the river, coaches and omnibuses would have been

entering central London from all other directions as well, with a similar class of patron. Still more surprising is

the regular Sunday morning service from Mitcham. Who would have needed to travel to Town on a Sunday?

It seemed that proprietors counted on their ‘regulars’ to bring them an assured income. Their outgoings were

heavy. First there were the costs of buying, stabling and feeding the horses. Horse fodder alone was a considerable

expense (some 15 shillings {75p} per week per horse) and the horses would have required frequent re-shoeing.

A horse which had cost perhaps £20 might work for only three or four years, and spare horses would have been

needed to replace any which became sick or disabled.

The heavily used coaches could easily cost £100 new and would have called for regular maintenance. In

addition there were the wages of the driver and conductor, and the government-imposed mileage tax (2½d or 3d

{1p or 1.25p} per mile, depending on the vehicle’s capacity), and the turnpike tolls.

Remarkably Merton had two turnpikes, one at Colliers Wood (‘Merton Singlegate’) and the other at The Grove

(‘Merton Double Gates’). The next turnpike going north was at Kennington. As only Royal Mail coaches were

exempted from paying tolls these three turnpikes must have placed a considerable financial burden on the

Holdens.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 13

Fares were by no means cheap. In 1830 6d (2.5p) would have had the spending power of at least £1 today. The

short-stage coach fare from Clapham to the City was 2s (10p) for and inside seat and 1s 6d (7.5p) for an

outside seat. The 6d flat fare was introduced when omnibuses began to replace coaches. However this applied

only to central London. In the suburbs the flat fare became 1s (5p). Bus and coach travel was too costly for a

workman, who was therefore compelled to live as near as possible to his place of employment, although some

amelioration came later when the newly expanding railways were compelled to initiate cheap fares for workmen,

and to that extent the railways can be seen as a social leveller.

Fares were by no means cheap. In 1830 6d (2.5p) would have had the spending power of at least £1 today. The

short-stage coach fare from Clapham to the City was 2s (10p) for and inside seat and 1s 6d (7.5p) for an

outside seat. The 6d flat fare was introduced when omnibuses began to replace coaches. However this applied

only to central London. In the suburbs the flat fare became 1s (5p). Bus and coach travel was too costly for a

workman, who was therefore compelled to live as near as possible to his place of employment, although some

amelioration came later when the newly expanding railways were compelled to initiate cheap fares for workmen,

and to that extent the railways can be seen as a social leveller.

The convenience of the short-stage coach had already been challenged by such lighter vehicles as the hansom

cabs and the broughams, which would ply for hire. But the greatest change came with the omnibus.

Barker and Robbins include an engraving of a vehicle crossing Blackfriars Bridge in 1798,4 a vehicle certainly

longer than a stagecoach. Nevertheless the omnibus, which at first supplemented and then supplanted the

short-stage coach may be considered a French development. A shopkeeper in Nantes named Omnes had the

bright idea of putting on a vehicle to bring customers to his premises from the outskirts. His slogan ‘Omnes

Omnibus’ (Omnes for all) was soon attached to the vehicle itself, Omnibus. The idea of wide use for such a

vehicle was taken up in Paris, where an English entrepreneur George Shillibeer was so impressed that he began

a service in London along the New Road and City Road, in 1829. Shillibeer can be regarded as the father of the

British bus (to which ‘omnibus’ came to be shortened).

In the early 1830s there 293 short-stage coaches and 232 omnibuses operating daily into central London, but by

the early 1840s the short-stage coaches had largely given place to the now all-conquering omnibus, which no

doubt took over the working of the former coach routes.

The advantage of the new omnibus over the short-stage coach was its greater capacity, accommodating

passengers both inside (on longitudinal seats) and on the roof – a box on wheels as coachmen derisively called

it. The floor was covered with straw, which must soon have become rank when trodden on by the boots of

passengers on inclement days.

The improved omnibus introduced in April 1847. Its clerestory roof provided longitudinal seating.

Illustrated London News 1 May 1847

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 14

The omnibus enabled costs to be spread over more passengers while still requiring only two horses. Nevertheless

it can hardly be claimed that it was a comfortable means of transport, particularly when crammed full. The

Times was moved to publish a list of do’s and don’ts for passengers, including:

The omnibus enabled costs to be spread over more passengers while still requiring only two horses. Nevertheless

it can hardly be claimed that it was a comfortable means of transport, particularly when crammed full. The

Times was moved to publish a list of do’s and don’ts for passengers, including:

‘Do not introduce large parcels – an omnibus is not a van.

‘Behave respectfully to females …

‘Keep your feet off the seats.

‘Do not get into a snug corner yourself and then open the windows to admit a North-wester upon the

neck of your neighbour.’5

With more passengers and more frequent stops an omnibus conductor (or ‘cad’) would certainly have had a

busier time than his short-stage counterpart. He stood on a step at the rear, and one of his duties was to ensure

that his bus was as full as possible. It is said that some conductors even went as far as to entice likely-looking

pedestrians to get on board, which could include getting the driver to veer to the other side of the road to pick

them up, and some were not averse to exceeding the licensed number of passengers if they thought they could

get away with it.

Liza Picard, in Victorian London,6 notes that a conductor was allowed to keep four shillings (20p) a day out

of his daily earnings. Presumably that was his sole remuneration. A driver received 34 shillings (£1.70) a

week. Their working day would begin at 7.45am at the latest, and there was no fixed knocking-off time.

Montague states that Samuel Holden’s name appears in local directories until 1855. The business had been

acquired by Philip Samson, but it is not clear whether the acquisition included the bus interests. I hazard the

guess that the bus business had passed to a man named Howes, for it is his name that appears in a list of

omnibuses delivered in 18567. Howes had acquired a contract with the newly formed London General Omnibus

Company.

Wimbledon historian the late Richard Milward states that as early as 1780 a coach ran three times a week

from the Rose & Crown to Charing Cross.8 By 1825 there was still only the one service, though it had become

daily by then. Inexplicably, by 1838/9 Wimbledon had no fewer than ten short-stage coaches or omnibuses

running daily to St Paul’s.

It is unlikely that the opening of a station on the London and Southampton Railway in 1840 sited in a field

midway between Wimbledon and Merton, would have attracted many passengers at first, as to reach the City

or West End they would have had to complete their journey from the original Nine Elms terminus by bus or

boat. Even the extension to Waterloo in 1848 (by this time the railway had become the London and South

Western) still meant a similar onward journey.

1.

E N Montague Lower Green West, Mitcham (2004) Merton Historical Society

2.

T C Barker and M Robbins A History of London Transport vol 1 – The Nineteenth Century (1963) Allen and Unwin, London, pp.15, 392

This work is the principal source for this article

3 .

J Feltham The Picture of London for 1805: being a Correct Guide to all the Curiosities (1805) London pp.415, 418

4 .

Barker and Robbins op. cit. plate 2

5.

The Times 13 January 1836, quoted in Barker and Robbins op.cit. p.36

6.

L Picard Victorian London: the story of the City 1840-1870 (2007) London

7.

Barker and Robbins op.cit. p.412

8.

R Milward Historic Wimbledon (1989) Gloucestershire and Wimbledon p.43

HOT OFF THE PRESS!

Some months ago we received an email enquiry from Sue Wilmott in Australia. Her great-great-great-greatgrandfather,

William Fenning, and his son, also William, were proprietors of the Ravensbury Printworks at

the end of the 18th and in the early 19th centuries. Sue’s great-great-grandfather, William Wood Fenning,

revisited Ravensbury in July 1850, probably for the funeral of his sister, and wrote a long poem looking back

over his years growing up at Ravensbury and mentioning quite a few people, places and events. Sue has

transcribed the poem, and added explanatory notes, and has generously allowed us to publish it in ourLocal

History Notes series. Illustrated with monochrome copies of William Wood Fenning’s watercolours of the

area, this booklet adds considerably to our understanding of our locality at this time.

RAVENSBURY: a poem written after a visit in 1850, recollecting childhood memories of people,

places and events, by William Wood Fenning is of 24 A4 pages, and costs £1.50 (£1.20 to members), plus

50p postage & packing. It is available from our Publications Secretary.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 15

DAVID LUFF examines

DAVID LUFF examines

On page 7 of the December Bulletin reference was made to a section of wall that once ran down the eastern

boundary of the old Liberty works, and it was described as having been part of the priory’s precinct wall.

However, from the photographs you can see that it did not at all resemble any of the three surviving sections.

These can be found, one alongside the Pickle in the grounds of Sainsbury’s supermarket, one in Station Road,

and one behind the maisonettes in Windsor Avenue.

The only section to have been restored

is the one in Station Road, and that is

because it is on a public road, and was

almost collapsing. The section in

Windsor Avenue is in very poor

condition, and that by the Pickle has

been left for nature to destroy, partly

covered by ivy and hemmed in by

shrubs and trees.

The former wall in the Liberty works

site may be marked on maps as part

of the priory wall, but was not

regarded as such when I worked

there. Could there once have been

two walls here – one a part of the

precinct wall and one just a boundary

wall? The former could have been

demolished and the name transferred

to the latter.

The wall at Liberty’s Printing Works, demolished 1989Photo: D Luff

The priory wall in Station Road, after repair. Photo: D Luff

Reference was also made to Liberty’s

having destroyed the section of wall

on their land. This is correct for a large

part of the wall, demolished in the last

war, but not for the remaining section

shown on the 1967 map. This was still

standing after the print works closed

in 1982. Its demolition took place in

1988/9, when the site was converted

into Merton Abbey Mills.

During the redevelopment in the late

1980s I cannot recall the retention of

this wall being considered, though it

fell within the environs of two listed

buildings and could have been

protected. The only people who may

now be able to explain why the wall

was demolished would be the Museum

of London, who are the experts on the

priory site, and who acted as advisers

to Sainsbury’s, the London Borough

of Merton, the developers and other

interested parties.

Letters and contributions for the Bulletin should be sent to the Hon. Editor.

The views expressed in this Bulletin are those of the contributors concerned and not

necessarily those of the Society or its Officers.

website: www.mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk email: mhs@mertonhistoricalsociety.org.ukPrinted by Peter Hopkins

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 173 – MARCH 2010 – PAGE 16

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY