Bulletin 172

December 2009 Bulletin 172

Growtes – the home of a rich man in 1554 D Haunton

The de Chastelains at old Church House J A Goodman

The (Society’s) Photo Project D Roe

and much more

VICE PRESIDENTS: Viscountess Hanworth, Eric Montague and William Rudd

BULLETIN NO. 172 CHAIR: Dr Tony Scott DECEMBER 2009

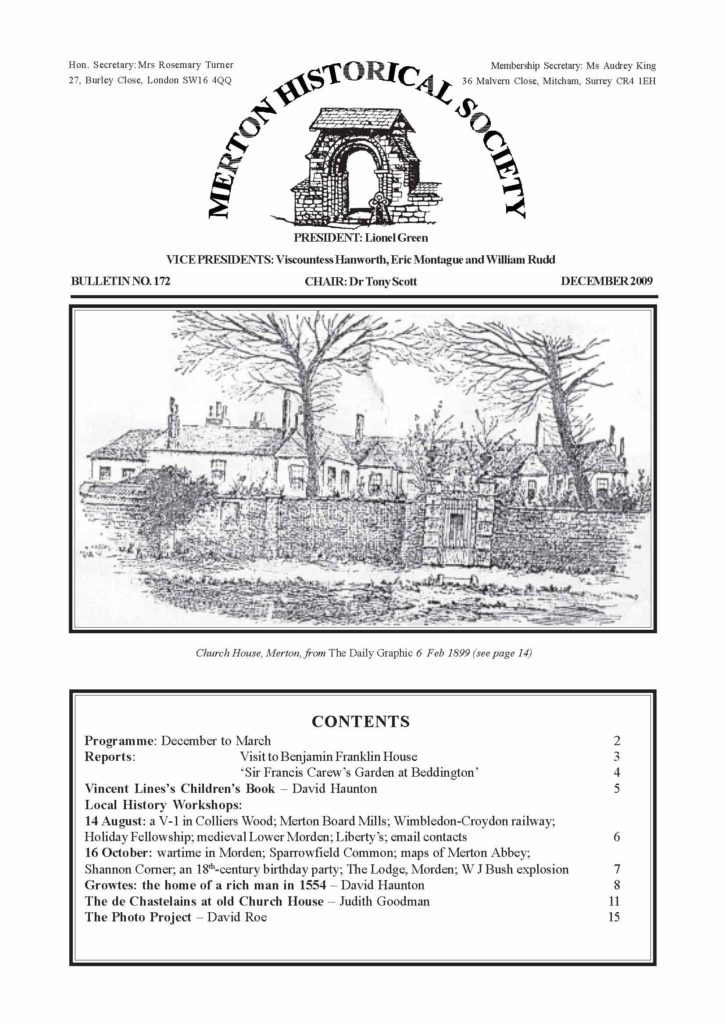

Church House, Merton, from The Daily Graphic 6 Feb 1899 (see page 14)

CONTENTS

Programme: December to March 2

Reports: Visit to Benjamin Franklin House 3

‘Sir Francis Carew’s Garden at Beddington’ 4

Vincent Lines’s Children’s Book – David Haunton 5

Local History Workshops:

14 August: a V-1 in Colliers Wood; Merton Board Mills; Wimbledon-Croydon railway;

Holiday Fellowship; medieval Lower Morden; Liberty’s; email contacts

6

16 October: wartime in Morden; Sparrowfield Common; maps of Merton Abbey;

Shannon Corner; an 18th-century birthday party; The Lodge, Morden; W J Bush explosion 7

Growtes: the home of a rich man in 1554 – David Haunton 8

The de Chastelains at old Church House – Judith Goodman 11

The Photo Project – David Roe 15

The Snuff Mill Centre is reached from the Morden Hall Garden Centre car-park by crossing the

bridge between café and garden centre and turning right along the main path. It is a ten-minute

walk from Morden Underground station. Morden Hall Road is served by many bus routes.

Please note that the National Trust strictly limits numbers to 50 at this venue.

Saturday 9 January 2.30pm Raynes Park Library Hall

‘Wren’s City Churches – Glorious Steeples and Hidden Treasures’

An illustrated talk by Tony Tucker, well-known expert on the City’s churches. He is a qualified

City of London Guide and Chairman of City of London Guide Lecturers Association, and he will

speak about Wren’s career as scientist and architect and then focus in detail on his City churches.

Raynes Park library hall is in Approach Road, on or close to several bus routes, and near to

Raynes Park station. Very limited parking.

Please use the entrance in Aston Road.

Saturday 13 February 2.30pm Christchurch Hall, Colliers Wood

‘The History of Tooting’

The speaker for this illustrated talk will be Rex Osborn, who is Chair of Tooting Local History

Group and is training to be a professional tour guide.

The hall is next to the church, in Christchurch Road, 250m from Colliers Wood Underground

station. Limited parking at the hall, but plenty in nearby streets or at the Tandem Centre,

200m south. Buses 152, 200 and 470 pass the door.

Thursday 25 February The Restaurant in the Park

Annual Lunch

See separate booking form enclosed.

Saturday 13 March 2.30pm St Theresa’s Church Hall

‘The St Helier Estate, a Home in the Country’

This illustrated talk by Margaret Thomas, Manager of Middleton Circle Library, Carshalton,

looks at the development of the estate from its farmland origins onwards, and discusses the

preservation of oral memories of some of its residents.

The hall is behind the church, on the west side of Bishopsford Road, Morden, about 200m

north of Middleton Road. Parking at the hall or nearby. Bus route 280 passes the door.

Visitors are welcome to attend our talks. Entry £2.

‘TALES AND TRAILS OF TOOTING TOWN’

This is the title of a guided walk to be presented by award-winning tour firm London Walks, and led

by our February speaker, Rex Osborn, Chair of Tooting Local History Group.

Meet 10.45am on Sunday 7 February 2010 outside Tooting Broadway Underground station.

£7 per head, or £5 for over-65s and full-time students. No need to book.

PUBLICATIONS

Don’t forget – the Society’s publications will be on sale at the meeting on 5 December. They make

excellent Christmas presents. Or contact Peter at www.mhs@mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 2

VISIT TO BENJAMIN FRANKLIN HOUSE

On 6 August a party of our members visited 36 Craven Street, off

Northumberland Avenue. We learned that for nearly 16 years between

1757 and 1775 this unassuming house was home to Benjamin Franklin

(1706-1790), scientist, diplomat, philosopher, inventor, and signatory of the

US Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution.

During his long stay in London Franklin’s main business was attempting to

mediate between Britain and its American colonies. Though he ultimately

failed in this endeavour he busied himself over the years with many other

enterprises. He was Postmaster for the Colonies; he improved his design

for a fuel-efficient stove; he invented the lightning rod – thus saving

countless lives; he proposed daylight saving time; he experimented with

inoculation; he invented the glass harmonica; he wrote countless letters

and articles; and he led a busy social life. (Not a family life, alas, as his

wife Deborah never felt able to face the sea voyage to join him.) He

knew everyone who mattered in London – including politicians, diplomats,

scientists, and medical men.

After a short talk and film we were able to have a leisurely journey through

the rooms, enjoying, as we proceeded, the costumed characters who came

and went, their (recorded) disembodied dialogue and the atmospheric

lighting effects. Nothing remains of the furniture from Franklin’s time,

though there are original fixtures, including mantelpieces, panelling, a

staircase and shutters.

In the last room, at the top of the house, we saw a modern

version of Franklin’s glass harmonica. This consists of a

series of chromatically graduated glasses which are

mechanically rotated and pressed with a damp finger,

producing clear sweet notes. Mozart and Beethoven both

composed for the instrument. We were able to try our skill,

with varying results – it proved difficult to extract a sound

from the smallest glasses.

Of course Franklin was not the only occupant of the house,

in which he had a parlour, bedroom, powder closet and

laboratory. It was run as a lodging house by the owner, a

woman called Margaret Stevenson, whose daughter Polly

was married to William Hewson, an eminent anatomist.

More than 2000 bones have been found on the site, and

are assumed to have been ‘left over’ from his teaching

sessions. He died from the main hazard of his profession,

septicaemia.

The house has had a chequered history. In the 1860s it

became a hotel, as soon did most of the houses in the street,

being so near Charing Cross. It remained a hotel, and

survived a wartime unexploded incendiary bomb, until the

street was threatened with demolition by plans to expand

the station in 1945. That however didn’t happen, and No.36

at first became temporary offices, and later a ‘squat’. By

the late 1990s it was nearly derelict, until the present owners stepped in and repaired it to a high standard, with

English Heritage keeping an eye on things. The house opened in 2006 on Franklin’s 300th birthday, and it is run

primarily as an educational centre for all ages, though you can also book it for your wedding reception etc.

This was a most interesting visit, bringing, as the publicity puts it, the Age of Enlightenment to life. We are

grateful to Sheila Harris for arranging it. The Historical Experience can be enjoyed Wednesday to Sunday.

Book on 020 7925 1405.

Judith Goodman

The Glass Harmonica (1761)

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 3

‘SIR FRANCIS CAREW’S GARDEN AT BEDDINGTON’

For this year’s Evelyn Jowett Memorial Lecture, on 17 October, John Phillips, Heritage Officer for the London

Borough of Sutton, took us into the fantastical world of Renaissance gardens, which he said at times he felt

were ‘very fussy and even twee’, when he spoke to us about the Carew garden at Beddington.

The garden was created by Francis Carew (1530-1611) about the late 1550s, although there had been a garden

there since the middle of the 14th century. The Carews were ‘courtier class’, just below the real aristocracy,

and held property in several counties.

Francis’s father Nicholas had been beheaded by Henry VIII, and the king then took over Beddington, but it was

given back to Francis by Queen Mary. He then kept out of politics and lived a ‘life of pleasure’, which included

the making of the garden. It was a water garden, with grottoes and fountains. One of its frequent visitors was

Queen Elizabeth.

Others included two from Germany. Baron Waldstein in 1600 recorded that there was a little river running

through the middle, a fishpond with a square rock in the middle, many statues and little artificial fish that seemed

to be swimming in the water. In 1611 the secretary of Landgraf Otto of Hessen-Kassel told of orange, lemon

and fig trees, and many little statues in the stream, with trout. Also two miniature corn mills, and a pleasure

house in which rain could be made to fall from the ceiling. And all was highly decorated.

For its date this was a radical garden. Unfortunately the earliest plan of it is dated 1820 and the earliest views

are late 18th-century prints. There was a moat round the house, and probably an outer courtyard.

The orangery of 1720 was built on the site of an earlier Tudor one, and one wall is still standing. This had stoves

for heat, and shutters which could be put in place to conserve heat, thought to have been the oldest in England.

Archaeology has revealed the foundations of an ornamental structure, consisting of, a possibly local, ferrous

conglomerate rock (which can also be seen in the walls of the church nearby), with tufa, which could have

come from France, and also abalone shell, large flints, chalk, and red gneiss (metamorphic rock). Part of a

hanging flowerpot has been found, with a green glaze.

Sir Francis’s

nephew Nicholas

Throckmorton

(later Carew) was

ambassador to

France, and his

sister Elizabeth was

married to Sir Walter

Raleigh. Remains of

tropical coral have

been found, and one

wonders if there is

any connection here

with Sir Walter and

his travels.

A very rare and beautiful small copper leaf was discovered, which could have been part of the grotto decoration.

John showed a slide of the recently restored Dudley garden at Kenilworth. Again there is a pond with a statue

in the centre, and again the little fishes swimming in the water. It could well be that the statue was by the same

sculptor as at Beddington. There is a similar grotto at Fontainebleau and it is possible that Sir Francis saw this

on his travels – he spent a year based in Paris. There seems also to be an Italian influence, but we do not know

if he went as far as Italy.

We all enjoyed this glimpse into the somewhat ‘quirky’ ideas of garden design during the 16th and 17th centuries.

[Two important articles have been published about the garden:

Roy Strong ‘Sir Francis Carew’s garden at Beddington’ in England and the Continental Renaissance:

Essays in Honour of J B Trapp ed. E Chancy and P Mack (1990) Woodbridge: Boydell pp.229-238

John Phillips and Nicholas Burnett ‘The Chronology and Layout of Francis Carew’s Garden at Beddington,

Surrey’ in Garden History (2005) pp.155-188]

Lorna Cowell

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 4

DAVID HAUNTON has a little more on

DAVID HAUNTON has a little more on

K

In Bulletin 168, I assumed that Shaping and Making, Vincent Lines’s children’s book describing country

crafts, was published some time after the end of the Second World War. Charles Toase later informed me that

the publication date was 1944. Brian Slyfield of the Horsham Society has now very kindly supplied me with a

contemporary review of the book from the West Sussex County Times of 29 December 1944. Thus it was

published for the Christmas trade in that year, and demonstrates the political priority for education, while the

country was still at war. The price of four shillings and sixpence was not cheap, when one considers that the

average wage was about six pounds per week.

After describing the contents, the reviewer comments ‘Mr Lines shows by his book that he has a real

understanding of the workings of a childish mind and through his descriptions he takes his reader into the small

workshops of those handymen whose wares will never be entirely displaced by the machine’.

I have recently seen

early drafts of some of

the pictures in the book.

Most of them closely

resemble the finished

artwork, but one, shown

here, stands out as

demonstrating a change

of mind by the artist.

The Toymaker, as published,

lithograph in three colours

While the broad concept remains the

same (workman on the left, facing right,

standing at a table) the details of man

and background are quite different.

Perhaps Vincent considered that he had

already drawn too many grey-headed

workmen with cap and moustache, and

needed a clean-shaven younger man for

variety !

Visitors to the Wimbledon Society’s

current exhibition of Vincent Lines’s

drawings will see the portrait which

reveals that he had a shock of bright

carroty-red hair. Presumably this is what

his sister meant when she said he took

after the Celtic side of the family!

The Toymaker, early draft, pen and pencil

sketch (private collection)

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 5

LOCAL HISTORY WORKSHOP

Friday 14 August 2009 – 6 present – Judy Goodman in the chair

.

……….David Haunton has interviewed Society member Bert Sweet, and reported his memories of being ‘bombedout’

from the family home in Fortescue Road, Colliers Wood, by a V-1 flying bomb in 1944, and of his

family’s experiences in the next year or so.

.

……….Cyril Maidment announced to our surprise that he had experienced the same bomb. He was waiting at a

bus stop in Christchurch Road, when the sirens sounded, and he fled to Colliers Wood underground station,

which he reached just as the V-1 exploded.

In his own research, Cyril has been trying to locate the scenes in some photographs of Merton Board Mills

that he found on a website, by detective work on consecutive editions of the Ordnance Survey maps of the

area,. One incidental result is that he has discovered that Liberty’s apparently knocked down about 100

yards of the Merton Priory wall.

Cyril then regaled us with the tale of the convoluted special train journey, Last In Last Out (LILO), to mark

the closing of the Wimbledon to West Croydon railway on 31 May 1977. This left Victoria at 11:00 am and

wound its way through every branch line and back yard in South London, to say nothing of Folkestone

Harbour via Ashford International, and Newhaven Marine via Gatwick Airport, reaching Wimbledon at 7:00

pm, and then trundling onwards. Cyril and son Gerald got off at Merton Park, sacrificing another four hours

before the train returned to Victoria at 11:11pm, via West Croydon, London Bridge (twice), Woolwich Arsenal,

Bromley North, and Elmers End!

Part of the timetable

.

……….Sheila Harris brought her memories and photographs of the Holiday Association, particularly of a recent

HF holiday in the Lake District. She gave us a short history of the organisation, from its foundation by

Thomas Arthur Leonard, a Congregational minister, in 1891 in Colne, through its expansion and subsequent

changes to its present-day form (such as the replacement of M and F dormitories by en suite rooms, and the

‘no alcohol’ rule by a fully-stocked bar).

.

……….Peter Hopkins gave us his current interpretation of the medieval settlement pattern in Lower Morden,

which seems considerably more straightforward than in some other parts of Morden.

Peter also reported that Sheila Fairbank had come across an illustration of a painting of William Henry Hunt,

c.1828, an old man who is said to have sailed on Captain Cook’s first voyage of Pacific exploration. (Cook’s

widow lived in Merton for many years.) Sheila has offered to do an article for a future Bulletin.

.

……….Bill Rudd brought along some photos of the Liberty factory site, including some excavations he conducted

on the Liberty allotments in 1962, and comparative pictures of the buildings in 1969 and nowadays.

.

……….Judy Goodman reported an email contact with a descendant of John Leach Bennett (calico printer of

Merton), and another with a researcher interested in James Lackington (bookseller and memoirist of Merton

and, among other places, Budleigh Salterton).

David Haunton

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 6

Friday 16 October 2009 – David Haunton in the chair

.

Peter Hopkins had been tracking down photos in the Local Studies Centre to illustrate a forthcoming

memoir by Ronald Read, who lived in Central Road from 1932 to 1957. In particular he had found photographs

annotated with comments on lives saved in severe local bombings.

Peter had also found more documents at The National Archives concerning the on-going disputes over the

rights of local people to use the 360 acres of Sparrowfield Common. The 16th-century ‘plotts’ were still

being used in the early 18th-century, though by that time the former landmarks were unrecognisable.

..Cyril Maidment showed two A3 maps he had prepared for the

London Open House weekend at the (Merton priory) Chapter

House under Meranton Way. One was this beautiful tracing of

the 1805 map of the 65-acre ‘Merton Abbey’ estate held at Surrey

History Centre. The other was a development of part of Dave

Saxby’s map on page 5 of the MOLAS book Merton Priory,

showing the location of contemporary buildings.

1933 1952 1967

1805

Cyril had also traced the life of a section of Priory wall, that had been progressively destroyed by the Liberty

silk-printing works despite the fact that it was in the care of the National Trust. In 1805 the wall was linked

to the north side of the High Path, Station Road, wall, which incorporated the High Gate, the location of

which can be seen. In 1933 most of it was still there. In 1952 half of it had been removed, the remainder was

National Trust. In 1967, only 20% remained, still National Trust. Today, 2009, there is nothing left.

.

Judith Goodman had been sent a photocopied view of an elegant but functional (Charles Holden) bus shelter

at Shannon Corner. She had been able to date the view to 1933/34, thanks to a film poster (for the Regal,

Wimbledon) in the background, advertising My Lips Betray, starring Lilian Harvey and John Boles. [Later

note: The Regal, in the Broadway, opened in November 1933, so the image probably dates from the following

year. The film, made in 1933, was held back briefly by the studio in favour of another one with the same stars.]

Dave Saxby, who has been trawling a number of old newspapers, had passed the following news item to her,

from the General Advertiser of Wednesday 29 November 1749:

Saturday last being the birthday of John Cecil, Esq; of Martin Abbey in the county of Surry, thesame was observed with great splendour, a great many cannon were fired, and the evening concludedwith bonfires and a great number of very fine fireworks and other demonstrations of joy.

John Cecil was a calico printer at Merton Abbey, and probably lived at Abbey House.

.

Rosemary Turner was gathering information on the area where she grew up, south of the western end of

Central Road, Morden, with a view to producing a Local History Note or something similar on a mansion,

a pond, Lodge Farm and Farm Lane (later Road). She had obtained an interesting series of maps.

.

David Haunton remarked on the end of SCOLA, the Standing Conference on London Archaeology.

Following an enquiry from a previous resident (now living in Chester), David had found reports in local

papers of the explosion in March 1933 at the factory of W J Bush & Co, perfume distillers. There is a good

photograph on page 117 of Eric Montague’s Phipps Bridge book.

Cyril Maidment

Next workshops: Fridays 15 January and 5 March at 2.30pm at Wandle Industrial Museum

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 7

DAVID HAUNTON has been investigating

GROWTES: THE HOME OF A RICH MAN IN 1554

DAVID HAUNTON has been investigating

GROWTES: THE HOME OF A RICH MAN IN 1554

1

(the formal record of the transaction) to explore the taste of a rich man in the mid sixteenth century.

The Man2

First, who was Edward Whitchurch? He was a haberdasher and bookseller who with his partner Richard Grafton

became printer to Henry VIII, and his son Edward VI. Among the firm’s publications were the Great Bible (the

first official translation into English, 1539), primers for school-children (one of which, in 1546, was the first book

printed in Welsh), church service books, and the first editions of the 1549 Book of Common Prayer. The business

was based in London; early addresses are uncertain, but from 1545 it was at the sign of the Sun in Fleet Street.

One reason Whitchurch remained in favour was that he was known as a zealous Protestant, publishing many

evangelical works during the reign of Edward VI (1547–1553). When Catholic Mary came to the throne in 1553,

and specifically excluded him from the list of forgiven Protestants in her coronation pardon, he speedily left the

country for the good of his health, selling Growtes as he did so.

The Bargain and Sale has 23 mentions of Edward, either by himself or ‘and his heirs’, but at one point refers to

‘Edward Whitchurch and Agnes now his wife’.3 This lady does not seem to be documented elsewhere.4 I suggest

that the marriage was a recent, second, one for Edward, that the document had originally been drawn up referring

to Edward and Agnes throughout; that Agnes had even more recently died; that the document was hastily rewritten

after her death; and that the sole remaining reference to Agnes is a slip of the scrivener’s pen. We do not

know where Whitchurch went after 1554, but he later married Margaret, the German widow of Archbishop

Cranmer, which may indicate that he went to Germany (possibly to Strassburg or Wesel, where there were large

enough communities to form English-speaking congregations). Or he may have gone to the Netherlands, with

which he had both professional links and religious sympathies. He eventually returned to London, and died in

Camberwell in 1562, survived by four adult children, presumably of his first marriage.5

The House

With Lionel Ducket, a mercer of London (who became Sir Lionel and Lord Mayor in 1572), Whitchurch was

‘granted’ (ie. sold) the manor of Morden and other properties by Edward VI,6 this purchase being completed on

30 June 1553. As the manor was leased to a tenant farmer, who occupied the old manorial centre, Whitchurch

looked elsewhere for a dwelling. Fortunately Growtes, a copyhold property inherited in 1540 by 13-year-old Henry

Lord, was on the market. The inventory for the ‘new-builded mansion house’ may have been originally drawn up

by Whitchurch himself (one heading is ‘Linen in my chamber’) but it was later amended with both additions and

deletions. The deletions presumably include some personal items he took with him.

Part of the Inventory in good 16th-century hand-writing – Copyright Surrey History Service K85/2/12 reproduced by permission

In the Chamber over the parlour next the lane

Inprimis a ioyned bedstede

Bed with

Itm a fether bed and a bolster

tester

Itm a wolle mattresse

and

Itm a mattresse of flockes

curtains

Itm fyve curtaynes of read say & grene to the same bed

Growtes itself was a large house of two storeys, situated on the east side of the highway (now Morden Hall Road),

within the grounds of what is now Morden Lodge. The name derives from John and Juliane Growte who were

admitted to a customary cottage and curtilage on the site in 1443/44. For a timber-framed house, the phrase ‘newbuilded’

would remind the new owner that the studding, wattle-and-daub and green timber of its construction could

be expected to slowly dry out and shrink or warp,7 and thus might soon require minor repairs. On the ground floor,

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 8

The Contents

At this period, wall hangings were a sign of social status, imitating the highly expensive

tapestries of the very rich. Chairs were generally rare, just beginning to replace forms and

settles, and are another sign of fashion and aspiration to upward mobility. Whitchurch had

eight, including four cloth-covered ones, a walnut chair with a wooden back, two old joined

(ie. carpentry) chairs, and a ‘Spanish chair covered with leather’, of which the leather was

probably painted or gilded.8 ‘Spanish chairs’ were being made in Flemish towns by this

date,9 which would perhaps have been a more likely source than Catholic Spain.

Visually, there was any amount of colour in the house – the ‘little parlour’ was also the

‘green parlour’, presumably painted, while elsewhere the colours of wall hangings, curtains

and chairs were noted. One chamber had bed-curtains of red and green ‘say’, the hangings

and one set of window curtains in green, the other set being merely ‘old silk’. There was Spanish chair

(Dictionary of Art

also a red chair with ‘pattern of brigus’ striped white and red, and two cupboard cloths of

Vol.29 p.314)

‘turkey dorny’. A second chamber had identically coloured hangings and curtains, further

brightened with two new coverlets of green and yellow ‘dorny’, and a chair covered with ‘pattern of briges’ in red

and green. A third chamber had ‘red say and green’ for all hangings and curtains, but a fourth chamber had only

a tester of red and green. The child’s bedroom had bed-curtains of ‘black buckram and yellow’ and hangings of

red and yellow buckram, and was also used to store a red ‘wagon cloth’ and six ‘cushions of tapestry for the

wagon’. Even the servants’ chamber had a tester of ‘red and green say’ and a chair with red cloth and green lace,

and was hung with ‘painted cloths with red and green water-flowers’. Downstairs, the main parlour had hangings

of ‘red and green say’, and a chair covered with blue cloth, while the hall was richly decorated with ‘hangings of

new painted cloths with roses and honeysuckles’. (One wonders if the servants’ chamber had inherited old

hangings from the hall, since the two rooms were apparently the same size.) The frequent use of the formula ‘red

say and green’ would seem to imply wide strips of red or of green, rather than cloths patterned in red and green.

Where did these colours come from?10 Mostly the dyes were made from common English plants. In general, reds

(including ‘turkey’) were obtained from roots of madder or bedstraw, or from kermes insects imported from

southern Europe. Blues came from woad leaves or some types of elderberry,11 yellows from the flowers of weld

(also called dyers rocket) or of dyers greenweed, and black from acacia-wood or some fungi. Green was obtained

by mixing yellow and blue. The colours so derived are subdued in hue when compared to present-day synthetic

dyes. English plants were usually cultivated in quantity specifically for the long-established dyers market. (The

Dyers Guild of London is first mentioned in 1188, while the Dyers Company received its first charter in 1471 and

is thirteenth in seniority of the 97 City Livery Companies.)12

Whitchurch had three carpets, two in the parlour and one in his chamber, two being of ‘dorny’. At this date,

carpets were not always laid on the floor, but might be draped over a table, as shown in his parlour, where the first

item was ‘a table with a frame & a carpet of green cloth’.

The various fabrics mentioned were expensive; in the sixteenth century13 ‘say’ was a fine lightweight cloth made

from carded or combed wool, often augmented with silk, while ‘dorny’ was a silk, worsted or part-woollen fabric, and

‘buckram’ a costly and delicate fabric of cotton or linen. ‘Pattern of briges’ is uncertain, but probably denoted a satin.

All these were probably of English manufacture, even though ‘say’ originated in the Netherlands in competition

with English cloth,14 and ‘pattern of briges/brigus’ is named for the city of Bruges, and ‘dorny’ for Doornik

(Tournai), both now in Belgium. However, there were also andirons ‘of Flanders work’ by the parlour fireplace

and a ‘Flanders pot’ in the kitchen, and we know Whitchurch gave his first printing contract (the ‘Matthew Bible’,

1537) to a printer in Antwerp, so it seems probable that he had maintained some Netherlands connections. This

seems the more likely since Antwerp had become a major centre of European printing by the 1540s.

An educated man, Whitchurch took away with him several books that were in all probability printed by his firm,

including a little Bible, a service book, a psalter and a book of prayers, as well as ‘divers’ others. He also took the

‘pair of virginals’, which despite the name was a single musical instrument (an early harpsichord), and perhaps also

the tester made from a old cope, an uncomfortably sacrilegious item removed from the chamber over the kitchen.

We have some evidence of his taste, quite literally, in the kitchen, where one of several mortars was reserved for

crushing garlic (so for use rather than ostentation), and one glass bottle was specifically for containing salad oil.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 9

The Pictures

The Pictures

15 Within the Growtes inventory, we

can be sure of ‘two pictures in frames’ in the third chamber, a ‘painted storie’ in the hall, and two ‘painted stories’

in the parlour, and slightly less confident of ‘two painted tables’ in the chamber over the little parlour, and ‘a pair of

tables’ in the parlour. The ‘square table with a frame’, also in the parlour, is probably a wooden table, but might be

a picture. Thus we have a total of at least five, probably nine and possibly ten pictures, which is a remarkable

number for a sixteenth-century English house. A study of the inventories attached to over 600 wills of wealthy

English people dating between 1417 and 1588 calculated that only 63 contained any work of art at all. Of these,

two collections of 16 and 17 pictures in 1533 are adjudged ‘very large’, the possessions of very wealthy men.16 So

we may draw our own conclusions as to the wealth and status of Edward Whitchurch.

Not the Fairy and the Gnome – A Cautionary Tale

The only picture where the subject is known was kept in the hall, and proved most intriguing. The description was

first read as a ‘painted storie of the faere and ye Nome’, which was assumed to be ‘The Fairy and the Gnome’.

This was exciting since ‘Gnome’ does not officially enter English until more than a century later, in a 1658

translation of the Works of Paracelsus. The Folklore Society did not know of such a tale, and suggested that

‘Nome’ might be ‘Naine’ (‘dwarf’ in French), to which I replied enclosing a copy of part of the manuscript. I then

discovered a little more about Paracelsus, physician, mystic and very opinionated; one of his teachings was that the

four classical elements were each inhabited by a characteristic spirit – gnome (earth), sylph (air), salamander

(fire) and undine (water). Did Whitchurch have a picture of a sylph and a gnome? And did his hangings painted

with ‘water flowers’ = water lilies = nenuphar, another Paracelsus symbol?

Fortunately, Dr Mark Page17 had almost simultaneously with my query

amended ‘Nome’ to ‘None’. The Folklore Society, writing again, concurred

and suggested very politely that ‘faere’ was wrong as well, supplying the

solution to our puzzle.18 The text we actually have is ‘the frere and ye

None’, ie. ‘the Friar and the Nun’, the title of a poem describing a simple tale

of sexual seduction. This was composed as an anti-clerical and anti-Catholic

satire,19 versions of which were very popular in the early 1500s. Explicit

prints of the subject were available, such as those engraved by Aldegrever

in the 1530s, and one would seem a suitable possession for a hot Protestant

such as Whitchurch to smile over. If it were a print, the ‘storie’ would have

been hand-coloured with water-based inks similar to modern poster paints.

It may not have been on public display in his hall, but pasted up out of

immediate sight inside the ‘painted and carved cupboard’ in the room (a not

uncommon Catholic practice with more conventional religious images – which

might improve the jest).

So, Check Your Sources Before You Leap !

Acknowledgement

I owe a very considerable debt of gratitude to Dr Caroline Oates, Librarian of the Folklore Society, and her colleagues at the

Warburg Institute, Bloomsbury Square, for sharing their expertise and kindly ushering me onto the right gnome/nun lines.

1 Surrey History Centre K/85/2/12 Bargain and Sale by Edward Whitchurch… to Richard Garth and Elisabeth his wife… transcribed by PeterHopkins and corrected by Dr Mark Page for Merton Historical Society (February 2009). All unattributed quotes are from this document; I havemodernised their spelling. My thanks to Peter for permission to use the results of his labours. Please note he is not responsible for my mistakes.

2 Most of this section is from Alec Ryrie Edward Whitchurch in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004-2005 OUP, and an e-mail from

Dr Ryrie to author 4 September 2009.3 Compare the number of references to the Garths: 17 mentions of ‘Richard and Elizabeth … or heirs … of Richard’, and only three of Richard alone.

4 ODNB loc.cit. ‘… first marriage or marriages are unrecorded …’

5 Edward, Helen, Elizabeth and a third daughter whose name is unknown.

6 Cal. Pat. Rolls 7 Edward VI pt xi m 13 [pp.233-4] (Reference courtesy of Peter Hopkins.)

7 Oliver Rackham Ancient Woodland 2003 Castlepoint Press pp.145, 457-98 María Paz Aguiló Spain VI, 2; Furniture 1517-1700 (iii) Chairs in Jane Turner (ed) Dictionary of Art 1996 Macmillan Vol.29 p.314

9 Stéphane Vandenberghe Belgium VI, 1; Furniture before 1600 in Jane Turner (ed) Dictionary of Art 1996 Macmillan Vol.3 p.582

1 0 Most of this section is from Su Grierson Dyeing and Dyestuffs 1989 Shire Publications (kindly loaned by Judith Goodman.)

1 1 Indigo was not imported in any quantity until the 17th century.

12 City Livery Companies in Weinreb and Hibbert (eds) The London Encyclopaedia 1983 Macmillan

1 3 Fabric definitions from dated citations in Oxford English Dictionary (second edition) 1989 OUP1 4 Jan de Vries & Ad van der Woude The First Modern Economy 1997 Cambridge UP p.2831 5 Susan Foister ‘Paintings in sixteenth-century English Inventories’ in The Burlington Magazine May 1981 pp.274-27516 Foister op.cit. pp.279-2801 7 Dr Page is Research Fellow of the Whittlewell Project of the Centre for English Local History, University of Leicester. His researchinterests lie in economic and social history, especially of medieval England, and in settlement and landscape history.

1 8 Letter, Dr Caroline Oates to author 18 June 2009

1 9 P J Croft ‘The ‘Friar of Order Gray’ and the Nun’ in Review of English Studies New Series Vol.XXXII, No.125 (1981) (Copy kindly

supplied by Dr Oates.)

The Friar and the Nun (reproved by a

representative of the secular German people).

Engraving by Heinrich Aldegrever, 1530

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 10

JUDITH GOODMAN recounts something of

THE DE CHASTELAINS AT OLD CHURCH HOUSE

JUDITH GOODMAN recounts something of

THE DE CHASTELAINS AT OLD CHURCH HOUSE

th century, it once belonged to the lay rectors of Merton. A newspaper article from 1911 described it as

Elizabethan brick at one end and ‘the very worst Georgian stucco’ at the other end, and as being about 50 yards

from end to end and containing more than 40 rooms.1

On 22 February 1849, on a sheet printed with the address ‘Royal Exchange Buildings, London’, the following

letter was written to ‘F. M. Loveland, Esq.’

‘Sir

In obedience to your request I have to inform you that the premises I have to offer are called “Church House”

situated opposite the church at Merton, within three quarters of a mile of Wimbledon Station of the South Western

Railway. They consist of a large old Mansion House, three yards separated by walls in one of which stands the

laundry with seven washing trays, and other conveniences – in another is a large School House with convenience

for children and in the third is a large Brick Building formerly a Barn but subsequently converted into Dormitories

for children. In this yard there is also Stable, Cowhouse & Workshops, and the whole is supplied with good water

from an Artesian Spring. The Gardens are about 3 acres in extent and the whole of these premises are enclosed by

a most substantial Brick Wall. There is also a field of 3½ acres of excellent land.

‘Of the suitability of the premises you may judge by the fact of their having been occupied for several years by

about four hundred pauper children of one of the metropolitan parishes from the Guardians of which I now hold an

agreement for the Lease. I now occupy the premises as a Boarding School, for which purpose I have been at

considerable expense in repairs and fittings. The premises are much larger than I require & therefore I would part

with them on being reimbursed for my outlay to the amt[?] of 280£ (including 40£ worth of Manure).

‘The agreement is that I am to pay 50£ per ann. the first year, ending at Midsummer next; and 60, 70 & 80£

respectively for the following three years, and 90£ for the remainder of the Term, abt. 30 years, this latter sum being

the original rental when taken by the parish from the freeholder. The freeholder I believe would grant power to

purchase if desired.

‘If the Guardians wish to view the premises I will appoint a time I will attend upon them.

‘I am

Sir

Your obt Servt

[James] Atkinson2

In May 1819 Church House had been advertised in The Morning Chronicle as follows:

SURREY.– To LET, a large FAMILY HOUSE

and good GARDEN, together upwards of Three Acres,

and surrounded by a brick-wall, situate near the Church, Merton;

distance eight miles from Westminster Bridge; a stage

goes daily to and from London; has lately been a school and is

well adapted for that or any other purpose requiring roomy

premises.– For particulars apply on the premises; or to Mr.

Chas. Smith, Merton Abbey, Surrey.3

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 11

Photocopy of an

‘aerial’ view of

Church House,

thought to have

been used to

advertise the de

Chastelain’s

school. The

original has

disappeared. The

view seems to date

from before 1866

when the north

aisle of the church

was built.

In 1820 Church House was leased by the Governors and Directors of the Poor for the parish of St Mary

Magdalen, Bermondsey, in order to house pauper children of their parish.

In 1820 Church House was leased by the Governors and Directors of the Poor for the parish of St Mary

Magdalen, Bermondsey, in order to house pauper children of their parish. Though Atkinson was mistaken in

claiming that the house had once accommodated 400 children – there were never more than 230 there – it was

a substantial house with useful ancillary buildings, in particular the old tithe barn. However, early in 1845, mainly

for reasons of economy and efficiency, the Bermondsey Guardians of the Poor closed the workhouse, and

removed the few remaining children back to Bermondsey.5

But they failed to dispose of the lease. In June 1848 James Atkinson of Dalston took an initial 4-year sublease

and opened a school,5 but, by February of the following year, we can see that he was looking for someone to

relieve him of the property. Mr Loveland seems to have represented the Guardians of another, unidentified,

parish, but, for whatever reasons, he did not proceed with the transaction.

Nevertheless, by July 1849 French-born Adolphe de Chastelain was leasing Church House from Atkinson and

‘endeavouring to establish a College or School on a large Scale, having already 20 pupils’.5

At the time of the 1851 census Adolphe had 37 boarding pupils, or ‘scholars’, in the language of the census, and

may well have had some dayboys too. He was 42 and had been born in Paris. His wife Maria (33) came from

Peterborough, and perhaps they had met and married in this country, as the eldest child listed, another Adolphe,

was born in Enfield. However they must then have returned to Adolphe senior’s native city, as the next four

children (Alfred George, Maria, Charles and Emma) were born there. Sadly, twin girls, Clara and Louisa, born

in Merton early in census year, both died later the same year. A French governess, from Paris, and an English

governess, Jessie Flight from Mitcham, would presumably have had the care of the little girls. A Scottish

housekeeper, two nurses, three maids and a cook completed the female staff. There was also a French

manservant, a gardener, and a cowman – fresh milk would have appealed to caring parents. To teach the boys

Adolphe employed a ‘Classical Tutor’, a ‘Professor of the German Language’, and a ‘Professor of French’.

The pupils ranged in age from six to 17. Nearly all had been born in Britain, but there were three brothers who

hailed originally from ‘van Diemen’s Land’ (Tasmania).

In 1857 Adolphe died, aged only 49. The sublease was taken over by a Revd George Elliott, who perhaps also ran

the school. However by the time of the 1861 census (Alfred) George de Chastelain was 23 years old and listed as

‘schoolmaster’. The widowed Maria was head of the household, and there were two little boys (twins?) aged

eight – another Alfred and Edwin. Two assistant masters were listed, and 38 boy pupils between eight and 17.

John Innes, with his brother James, bought Church House and its land in 1868 – it was one of their early

purchases. (The vendor was Charles Robert Mackrell, heir to the property once owned by Charles and Admiral

Isaac Smith.) Innes thus became de Chastelain’s landlord. In 1888, in the run-up to the first county council

elections, in which Innes stood for the Wallington division (which included Merton) George de Chastelain would

be a member of Innes’s campaign committee.

In the 1871 census return George de Chastelain, aged 33, called himself ‘schoolmaster principal’. His 26-yearold

wife Edith had been born in New York, and there were already four young children. Only nine pupils,

between 9 and fifteen, are listed, and one ‘Classical Teacher’.

However, the 1881 census lists 38 ‘scholars’, between 7 and fifteen, and four assistant teachers, at what was

by now called ‘Merton College’. There were also four more young de Chastelains.

There are occasional references to de Chastelain and the school in local records. Diagonally opposite Church

House stood the National Schools, and in December 1875 Edward Pillinger, the boys’ headmaster, recorded

that ‘Mr de Chastelain called to complain about some of the boys injuring his property by throwing stones’.6 In

1877 Pillinger noted the admittance to the National School of a new boy, from ‘De Chastelaine’s[sic] College’.6

Presumably the boy’s family circumstances had changed for the worse. Let us hope his fellow pupils treated

him kindly.

In 1881 at Wandsworth Police Court 18-year-old Fanny Turner was found guilty of stealing articles while in the

service of de Chastelain. They included another servant’s stays, pots of jam and items belonging to the family.

She had a previous conviction for stealing and was sentenced to six weeks hard labour.7 Again at Wandsworth

Police Court, in 1892, a Spanish pupil called Carlos Castillo was charged with obtaining £1 from de Chastelain

by means of a trick, and stealing a bicycle worth £16, but the charges were withdrawn.8

In April 1887 the pupils gave a musical entertainment, with comic songs, ballads, and violin, banjo and piano

recitals, plus a farce called Borrowed Plumes. After the concert the headmaster presided over a dance.9

There was a distressing episode in 1890, when a 12-year-old boy from the National School, excluded for

stealing other pupils’ lunches, and found to be emaciated, having been systematically starved by his father and

stepmother, was taken to Church House to be weighed.6,10 Was it the only premises with scales?

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 12

By 1891 George was a widower, and was assisted by Charles, his second son. But only six scholars are listed.

It is likely that George soon gave up the school. A newspaper article from early 1899 refers to the school as

having been discontinued ‘about six years ago’,

By 1891 George was a widower, and was assisted by Charles, his second son. But only six scholars are listed.

It is likely that George soon gave up the school. A newspaper article from early 1899 refers to the school as

having been discontinued ‘about six years ago’, and, in The Times for 23 March 1893 under ‘Board and

Residence, Apartments, &c’ is the following advertisement:

BOARD and RESIDENCE, near Wimbledon . – A

Gentleman offers same in his charming country house. Old

walled-in garden of three acres. Bath (h. and c.), tennis-court, full-

sized billiard table. Easy access to river. Late dinner. Terms from

30s. References required. – Chastelain, Church-house, Merton, Surrey.

However, this venture does not seem to have prospered, as by September of the same year a columnist in a

local paper was writing, ‘The rumour that Merton College is to be pulled down will be heard with regret, but

hardly with surprise. It is the veriest ramshackle of a place, and the cost of restoration would be too great to

admit of a sufficient return, by way of rent, for the outlay. … [F]or forty years or so it has been used as a school

by the Messrs de Chestelain[sic]. Is it any good suggesting to Squire INNES that he should offer it to the

Wimbledon Local Board or the Croydon Rural Sanitary Authority as a fever hospital?’12

It was not pulled down, yet, nor did it become a fever hospital. It remained unoccupied, while providing useful

accommodation for parish meetings and for fund-raising bazaars, and occasionally as an emergency classroom.

No one lived in Church House again. One wing was demolished in 1911 and the rest of the house went in 1923.

Three Pupils

We know something about three of the school’s pupils. Robert Williams

Buchanan (1841-1901) was an important literary figure in his day, writer of

many novels, plays and essays, but best known now for his savage attack, initially

in The Contemporary Review, on D G Rossetti and ‘The Fleshly School of

Poetry’. The son of great admirers of reformer Robert Owen, he was at first

educated at a school at Hampton Wick,13 where the food was so meagre and

unpalatable that he ate snails in the garden to stave off hunger. He was then, to

his relief, sent to the ‘French and German College’ at Merton. This was during

the 1850s, when Adolphe was the master, and Buchanan described it as ‘a large

school, excellently conducted’, but added, rather alarmingly, that ‘it resembled in

some respects Mr Creakle’s establishment’. I am inclined to think that Buchanan

was confusing the ferocious headmaster in David Copperfield with the much

kindlier Dr Blimber, Paul Dombey’s schoolmaster in Dombey and Son.14

(Henry) Havelock Ellis (1859-1939), who grew up to become an editor, translator, reviewer, and sexologist,

was a dayboy at Church House for three years, leaving when he was 12. The Ellis family lived at what is now

121 Hartfield Road, Wimbledon. The headmaster at that time was Alfred George. Ellis described the place as

a ‘low but very broad house with two wings’ with, to the left, ‘the schoolhouse [added in the workhouse era]

with various farm buildings and out-houses. … There was a little old theatre [the tithe barn] … transformed into

a combined swimming-bath and gymnasium.’ He reckoned the school as ‘entitled to rank as fairly good’.

Despite the great age range among the pupils there was no bullying. The only hint of irregularity that he recalled

was his once being asked by a master to take a note to one of two pretty dressmaker sisters who attended the

church. Ellis learned some Latin and rather more French at the school, played some cricket in the field and

sometimes, by invitation, croquet on the house lawn. He described George de

Chastelain as ‘a pale compact little man of French descent, though completely

anglicised, who made a competent and energetic headmaster, maintaining his

authority with a touch of sarcasm’. To the boy it seemed that de Chastelain ill-

treated his wife, ‘a rather pretty American with a low voice and a faded crushed

air’. Unaware (presumably) of this sympathetic view of her life, Edith de

Chastelain once reported Ellis to her husband for absent-mindedly failing to raise

his hat to her in the street, and his manners were put down as merely ‘passable’

in his quarterly report. Once when Ellis was daringly walking arm-in-arm through

the ‘poppied cornfields between Merton [Park] station and the College’ with a

young girl who was staying with his family, George de Chastelain unexpectedly

appeared. Boldly Ellis raised his cap but kept his arm where it was. Though

Alfred later checked with Ellis’s father who the girl was there were no

repercussions this time.15

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 13

The third pupil we know something about was

William Turnour Thomas Poulett (18491909).

He had been born six months after his

mother Elizabeth married William Henry Poulett,

nephew of the fifth Earl Poulett. William Henry

left his wife soon after the birth, always denied

the child was his and never provided for him,

though he made an allowance to his wife for the

rest of her life. The boy had his early education

at Church House under Adolphe de Chastelain,

and his later fluency in several languages,

particularly French, may have been acquired

there. Then followed an attempt to pursue a

career on the stage, and, aged 19, he married a

dancer, Lydia Ann Shippy.

The third pupil we know something about was

William Turnour Thomas Poulett (18491909).

He had been born six months after his

mother Elizabeth married William Henry Poulett,

nephew of the fifth Earl Poulett. William Henry

left his wife soon after the birth, always denied

the child was his and never provided for him,

though he made an allowance to his wife for the

rest of her life. The boy had his early education

at Church House under Adolphe de Chastelain,

and his later fluency in several languages,

particularly French, may have been acquired

there. Then followed an attempt to pursue a

career on the stage, and, aged 19, he married a

dancer, Lydia Ann Shippy.

Unexpectedly William Henry had succeeded to

the title, and was now the sixth Earl Poulett.

William Turnour Poulett took to calling himself Viscount Hinton, the courtesy title always used by the eldest son,

though the earl still refused to see him and, just in case, used the law to entail the estate away from him. Poor

‘Viscount Hinton’ meanwhile sank in his profession until he became a street organ-grinder. However, a Poulett

family connection helped the family financially: William and Lydia’s son became a tea planter in Ceylon and

their two daughters were educated in France.16

The organ-grinder and his wifeIllustrated London News 28 January 1899

When the earl died in 1899 he left as his heir

his 16-year-old son John by his third marriage.

But the press immediately took up William

Turnour’s case:17 an organ-grinding viscount

was irresistible. The Daily Graphic even

published an article headed ‘ “Viscount

Hinton”’s Old School’, illustrated by two

drawings of the empty Church House

buildings.11 Many interviews were published,

with much detail about the claimant’s modest

way of life in Henry Buildings, Pentonville.

But the story was a short-lived wonder and

he was soon forgotten. In July 1903 a case

was finally brought before the Committee of

Privileges of the House of Lords. The verdict

was that though born in wedlock William

Turnour Thomas Poulett was illegitimate.18

The dream was over. He died a few years

later in the Holborn Union Infirmary.16

1.

Daily Chronicle 21 January 1911 2. Merton Heritage and Local Studies Centre

3.

The Morning Chronicle 21 May 1819. I am grateful to David Saxby for this reference. Charles Smith, a wholesale watchmaker, and his

brother Admiral Isaac Smith owned the Merton Abbey estate and other property in Merton. It was Isaac rather than Charles who owned

Church House. Nothing is as yet known of the school that had gone by 1819.

4 .

Southwark Local Studies Library: Minutes of the Governors and Directors of the Poor for the Parish of St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey

5.

London Metropolitan Archives: Minutes of the Bermondsey Board of Guardians

6.

Merton Boys School Log Book: transcript at Surrey History Centre

7.

Mid-Surrey Gazette 20 August 1881

8.

Surrey Independent & Mid-Surrey Standard 20 February 1892

9.

Surrey Independent & Mid-Surrey Standard 9 April 1887

10. Surrey Independent & Mid-Surrey Standard 3 and 10 May 1890

11. The Daily Graphic 6 February 1899 p.5

12. Surrey Independent & Mid-Surrey Standard 30 September 1893

13. This school was part of the community established by ‘sacred socialist’ James Pierrepont Greaves (1777-1842), a son of Charles Greaves,

calico-printer of Merton Abbey. J E M Latham Search for a New Eden (1999) London, Associated University Presses pp.155, 171

14. Harriett Jay Robert Buchanan: Some Account of his Life … (1903) Unwin, London pp.12-13

15. Havelock Ellis My Life (1940) Heinemann, London pp.54-56

16. Colin G Winn The Pouletts of Hinton St George (?1968) London pp.95-104

17. Wimbledon News 28 January 1899; Illustrated London News 28 January 1899 p.115; 4 February 1899 p.161; 28 January 1899 p.8; 18

February 1899 p.14

18. The Times 27 May 1903

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 14

PROGRESS ON THE SOCIETY’S PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD PROJECT

PROGRESS ON THE SOCIETY’S PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD PROJECT

Some 18 months ago Eric Montague kindly agreed to lend his collection of colour slides of Mitcham to the Society

for scanning, converting to digital format, and professional archiving by the Surrey History Centre. This has now

been completed: it has taken longer than anticipated, owing to other commitments, and also the time needed to

prepare a listing of the photos with information about the location and local history in addition to the captions on the

slides. There is a total of nearly 1000 photographs, covering 17 districts of Mitcham, taken between the mid-1960s

to the early 1990s. They also include photos of old postcards, paintings and illustrations relevant to the history of

Mitcham. This collection demonstrates the importance of keeping a photographic record of the local area today,

as Eric Montague has done for Mitcham, starting over 40 years ago, as much of Mitcham has changed radically

since then. An example is shown here – a photo taken in 1968 looking west to Merton from Christchurch bridge

in Colliers Wood. The railway has since been replaced by Merantun Way, the factories on the right and the

Merton Board Mills beyond have been replaced by the Sainsbury’s and M&S stores and their car parks.

David Roe

CALLING TRI-ANG TOYMAKING PERSONS

The V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green has recently begun a three-year project to document and

digitise their archives of four 20th-century British toymakers – Lines Bros, Abbatt Toys, Palitoy and Mettoy.

There is more information on the website at www.vam.ac.uk/moc/collections.british_toy_making/index.html which

leads to an interesting blog on the project containing further pictures.

As part of this project, Sarah Wood, the curator, would like

to get in touch with people who worked in the factories or

elsewhere across the industry. She has asked us for help

in locating past workers at Lines Bros (or anyone else who

has any information) who would be willing to share their

memories with her. Sarah may be contacted by phone 0208983-

5212, by e-mail at sl.wood@vam.ac.uk or by letter

at V&A Museum of Childhood, Cambridge Heath Road,

London E2 9PA. Or really shy people could talk to

committee member David Haunton on 020-8542-7079.

[The picture is from the website and is captioned

Doll’s house and fort assembly room, Tri-Ang factory,

Merton, c.1950]

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 15

COMMITTEE MEMBERS 2009-2010

The minutes of the AGM are enclosed with this Bulletin.

SUBSCRIPTION REMINDER

Subscriptions for 2009-10 are now overdue. Please note that this will be the last Bulletin to reach you if we

have not received your payment by the time of the next issue.

A membership form was enclosed in the September Bulletin. Current rates are:

Individual member £10

Additional member in same household £3

Student member £1

Cheques are payable to Merton Historical Society and should be sent with completed forms to our new

Membership Secretary.

Letters and contributions for the Bulletin should be sent to the Hon. Editor.

The views expressed in this Bulletin are those of the contributors concerned and not

necessarily those of the Society or its Officers.

website: www.mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk email: mhs@mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk

Printed by Peter Hopkins

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 172 – DECEMBER 2009 – PAGE 16

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY