Bulletin 169

March 2009 Bulletin 169

A Cricket Souvenir C Maidment

Jean Reville: Merton’s Racing Motorist – Part 1 D Haunton

The ‘Highgate’ of Merton Priory C Maidment

The Wandle in Literature 6. John Ruskin J A Goodman

and much more

PRESIDENT: Lionel Green

VICE PRESIDENTS: Viscountess Hanworth, Eric Montague and William Rudd

BULLETIN NO.169 CHAIR: Dr Tony Scott MARCH2009

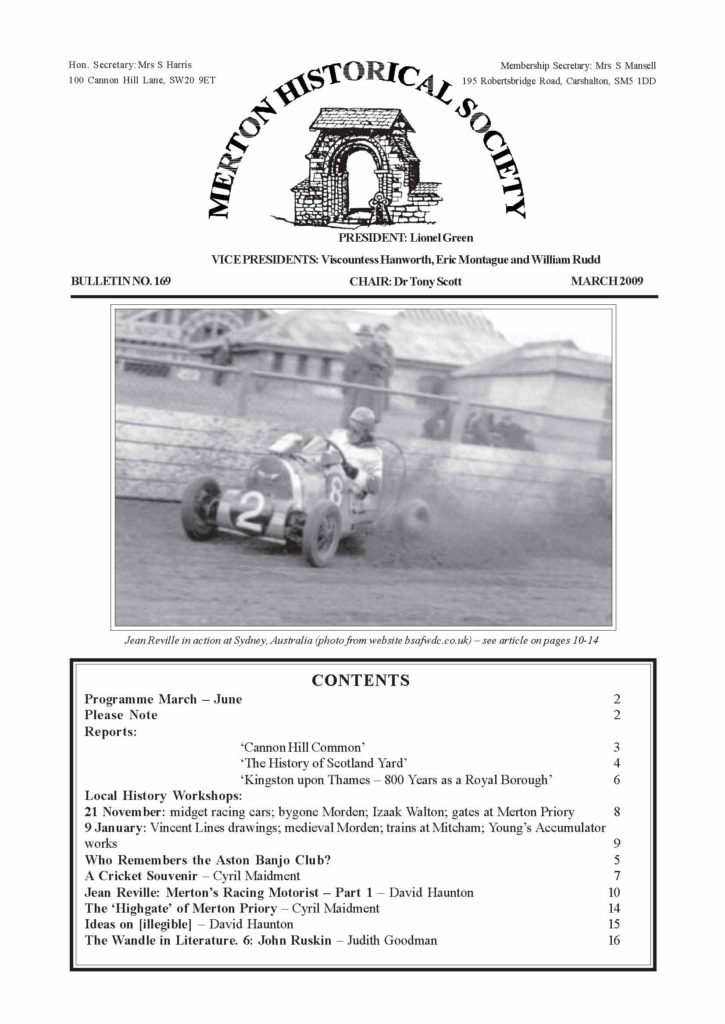

Jean Reville in action at Sydney, Australia (photo from website bsafwdc.co.uk) – see article on pages 10-14

CONTENTS

Programme March

Please Note

– June 2

2

Reports:

‘Cannon Hill Common’ 3

‘The History of Scotland Yard’

‘Kingston upon Thames – 800 Years as a Royal Borough’

4

6

Local History Workshops:

21 November: midget racing cars; bygone Morden; Izaak Walton; gates at Merton Priory 8

9 January: Vincent Lines drawings; medieval Morden; trains at Mitcham; Young’s Accumulator

works 9

Who Remembers the Aston Banjo Club? 5

A Cricket Souvenir – Cyril Maidment 7

Jean Reville: Merton’s Racing Motorist – Part 1 – David Haunton 10

The ‘Highgate’ of Merton Priory – Cyril Maidment 14

Ideas on [illegible] – David Haunton 15

The Wandle in Literature. 6: John Ruskin – Judith Goodman 16

PROGRAMME MARCH–JUNE

Saturday 28 March 2.30pm Raynes Park Library Hall

‘Archaeology in London over the Centuries’

Nathalie Cohen is team leader for the Thames Discovery Programme (archaeology of the Thames

foreshore), and is also Cathedral Archaeologist for Southwark Cathedral. Her presentation will explore

the development of the archaeology profession and the growth in understanding of London’s archaeology.

Raynes Park Library hall is on or close to several bus routes and near the station.

Very limited parking.

Please enter the hall via the Aston Road entrance.

Saturday 25 April 2.30pm Merton Park Primary School

‘Merton Park 100 Years Ago’

This talk has been arranged jointly with the John Innes Society. The speaker will be David Roe,

our Hon. Treasurer, who is also a John Innes Society committee member, and has responsibility

for its local history activities.

Merton Park Primary School is in Church Lane, Merton Park. It is a few minutes walk from Kingston

Road buses and the Merton Park Tramlink stop.

Please use the Erridge Road gate.

Thursday 21 May Visit to Godalming

Travel will be by train. We shall have a guided tour of the museum and a town tour.

Free, but donations welcomed.

Tuesday 16 June 11.30am The Musical Museum, Brentford

We have booked a guided tour, which will cost £6.50 per person.

PLEASE NOTE !

At some of the venues used for our meetings Merton Historical Society has to accept a hiring condition restricting

the number of people who can be accommodated. The restriction may be because of the age of the building and

is for health and safety reasons and/or insurance purposes. If you arrive after the permitted number has entered

you will be asked to leave, in the interests of the safety of our members and visitors and to conform with the

hiring agreement. The meeting will not proceed until the reduction in numbers has been achieved. As you know,

we use a variety of venues around the borough, and some of the large ones do not seem as popular as the

smaller venues, such as the Snuff Mill – at which the permitted number is only 50.

It is for safety reasons that members and visitors are asked to enter their names both signed and

printed on the list at the door.

Audrey King

TALK BY DAVID ROE – MERTON PARK 100 YEARS AGO

This talk is on Saturday April 25, at 2.30 p.m. in Merton Park Primary School, Erridge Road. It forms part of

the Society’s programme, and is organized in conjunction with the John Innes Society, who will be celebrating

this year the centenary of the opening of John Innes Park on August 1, 1909. The talk will be a slide presentation,

and will draw upon the researches by Judy Goodman and others into the history of Merton Park, and the

collection of photographs held by the John Innes Society. It will cover the nature of the developing suburb 100

years ago, and the people and events of this fascinating period, including

¨ The bequest of John Innes (died 1904) of land and money, which led to the establishment of the public park

and the Horticultural Institution that still bear his name.

¨ The fine houses and other buildings designed by the architect Sydney Brocklesby.

¨ The activities of Rose Lamartine Yates, leader of the Wimbledon & Merton suffragettes, who lived in

Dorset Hall, Merton Park.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 2

‘CANNON HILL COMMON’

After the formal business of the Annual General Meeting on 8 November, the large audience was treated to a

presentation by Carolyn Heathcote, who is secretary to the Friends of Cannon Hill Common. This energetic

group was formed about ten years ago, and apart from keeping an vigilant eye on the Common, and effecting

many improvements, they publish a regular newsletter and arrange two open days each year. Carolyn pointed

out that it was never a real common. Before the purchase in 1926 of its 53.5 acres for £ 17000 by Merton and

Morden Council it had always been part of a private estate. It was a council decision to call the new public open

space Cannon Hill Common – for the sake of alliteration perhaps.

And the name Cannon Hill? Nothing to do with Cromwellian artillery during the Civil War, and everything to do

with the fact that what is now the Common is a small part of the land once held by the Augustinian canons of

Merton Priory. Canondownehyll was the medieval name. With the surrender of the priory in 1538 the land

came to the Crown, and was later sold on to private individuals who at that time farmed it as non-residents, for

the first evidence of a house at Cannon Hill dates only from 1763. It was probably built for a William Taylor,

who held leases on other land nearby, and was described later in Edwards’ Companion from London to

Brighthelmston as ‘a white house situated on an eminence commanding a pleasant and extensive prospect to

the east’. The ornamental canal at the bottom of the slope may have originated as the clay-pit used for making

the bricks for the house.

Cannon Hill was bought in 1832 by Richard Thornton (1776-1865), who made a fortune first in the Baltic trade,

dealing in goods such as tallow, timber, furs and hemp, and earning himself the nickname ‘Duke of Danzig’, and

later in shipping insurance and also the East India trade. He also served at one point as Master of the Leathersellers’

Company. He was generous to the poor of Merton, and on his death in 1865 left money for Merton’s National

Schools. His total estate was about £3,000,000 and went mainly to a nephew, though Thornton’s children by his

long-term mistress were not forgotten. It is likely that the house was never occupied again, and it was pulled

down probably in the 1890s.

In 1925 George Blay, a

property developer, bought the

estate, which then included

much of Raynes Park that was

still undeveloped. Using the

post-war government subsidy

scheme he went on to build

hundreds of houses there, at the

same time offering to sell to the

Council the piece of land we

now know as Cannon Hill

Common. Dog walkers, nature

lovers, picnickers and anglers

have cause to be grateful to him

and to the Friends. Carolyn

illustrated her enjoyable talk

with an interesting selection of

slides.

Judith Goodman

Early postcard of Cannon Hill ‘Park’ – no postmark

MERTON HERITAGE CENTRE

There is still time to see The Merton Heritage Alphabet, which is on till 28 March. Tel: 8640 9387

THE LOVEKYN CHAPEL

This year Kingston’s Lovekyn Chapel (see page 6) is 700 years old. Information about celebratory events all

year can be found at http://www.kingston-grammar.surrey.sch.uk/events/lovekyn700.html

HONEYWOOD MUSEUM, CARSHALTON

The museum currently has two exhibitions: one about Henry VIII and Nicholas Carew, and, by way of contrast,

one about Sutton’s Route 654 trolleybus, which ran from 1935 to 1959. For details tel: 020 8770 4297

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 3

‘THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND YARD’

At Raynes Park Library Hall, on 6 December 2008, Maggie Bird, Head of the Historical Section, Metropolitan

Police, delivered a lively and splendidly illustrated ‘swift dash’ through centuries of London police history.

Policing in London by a formal organisation began in 1663 with a force of night-watchmen, charged with raising

the alarm when wrongdoing was discovered, but with little actual authority. Mostly recruited from ex-soldiers,

they were raised soon after the Restoration of Charles II; hence their nickname of ‘Charleys’. Never very

effective, over the next 150 years they were the butt of many jokes and caricatures, and not infrequently subjected

to indignities by young men-about-town.

Around 1750, Henry Fielding JP organised a mobile group of ‘thief-takers’ working from his magistrates office

and court in Bow Street – the originals of the ‘Bow Street Runners’. They wore plain clothes, not a uniform, and

essentially formed a detective organisation rather than a police force. Some years later, Bow Street began the

Horse Patrol on all heaths and commons within 20 miles of Charing Cross, keeping an eye on such well-known

haunts of footpads and highwaymen as the little hamlet of Heath Row in Middlesex. (This is still effectively the

Metropolitan Police District.) These chaps did wear the famous scarlet waistcoat which gave rise to their nickname

(supposedly a reference to the scarlet flowers of the runner bean). They were also known as ‘Robin Redbreasts’.

The Bow Street organisation continued until 1840, when the Metropolitan Police assumed its responsibilities.

Then in 1798, Pat Colquhoun, a police magistrate, instituted the Thames River Police force, to counter piracy on

the river. This was not quite the first police force in London, since a basic City police force, much restricted as to

authority and boundaries, had recently evolved from the old watch system.

In the early 1800s London was a fairly lawless place, with many ‘rookeries’ where desperately poor people lived

in overcrowded and insanitary conditions. Social deprivation was widespread, and cheap gin the main relaxation,

apart from public hangings. Drunkenness was a perennial problem, as it was much safer to drink beer than the

available water. Criminality was rife; a common form of assault was the use of a wire, to effect strangulation or

garrotting. Against this background, Sir Robert Peel introduced a Metropolitan Police Bill in 1822, which failed.

He tried again in 1828 and succeeded. The Metropolitan Police was established in 1829, with its HQ in Whitehall

Place and its first police station at the rear of the building, approached by way of Scotland Yard (so named as the

area behind the early London lodging suite of the kings of Scotland within Whitehall Palace). Police stations were

marked with the nowadays traditional blue lamps – all except Bow Street, which had white ones until recently

(apparently Queen Victoria often visited a house in the street, and objected to the blue colour).

Under the first pair of Commissioners, Dick Mayne (a lawyer and

manager) and Sir Charles Rowan ( a soldier), conditions of service

were onerous and strictly regulated. Each constable was expected

to patrol 20 miles a day, on foot; the uniform was to be worn at all

times (if a man was on duty he wore an armband to signify this),

comprising a blue tail coat, reinforced top hat (in which

‘refreshments may be carried’), an anti-garrotte collarand a leather

stock; he was to carry a rattle (not a whistle) and a truncheon.

Helmets and tunics were introduced in 1864. Originally there was

no pension, but there was the prospect of a gratuity after 20 years

service. The first establishment was for about 3500 men, who

were mainly recruited from labourers, clerks and ex-soldiers.

Initially there was a high drop-out rate, mainly from drunkenness

(the first two recruits, warrant numbers 1 and 2, lasted all of four

hours in service).

Despite riots against the police, assaults on individual officers, and public meetings to abolish them, they persevered.

To combat riots in the 1860s they had cutlass training (the last time the Army assisted the Metropolitan Police).

Their responsibilities expanded so that they became the emergency service – there were no ambulance or public

fire brigades, so equipment began to include stretchers, braziers and fire buckets, and handcarts fitted as ambulances

with leather hoods and solid wheels. When eventually fire stations arrived, they were often built next door to an

old police station (the police kept the ladders…). Not only did a constable have to know the law, and how to control

traffic, using a semaphore system, he needed knowledge of other specialities like cattle driving and animal diseases

– there were many slaughterhouses, tanneries, soap and glue factories – not to mention public health and the

necessity of keeping the streets clean. At least during the cholera epidemics it was emphatically laid down that a

constable was not to distribute medicine.

‘The Real Blue Collarer in London’. Hostility to the

new police is compared in this 1832 caricature to

the dread of cholera.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 4

By the 1890s poor living conditions still prevailed – social problems led to horrible crimes such as those of Jack the

Ripper – but the Met Police persevered and innovated. Conditions of service improved; many police stations were

built 1890-1908 with an inspector living on the premises and a section house providing single accommodation for

constables. Old age pensions were instituted in 1890. Headquarters itself moved to New Scotland Yard on the

Victoria Embankment in 1890, and then in 1967 to its present location at the new New Scotland Yard, on Victoria

Street in St James’s. Cycle patrols were introduced; the first radio car (actually a lorry) was used at the Epsom

Derby in 1915; women police constables were accepted

in 1919 – wartime service as WPCs was strictly speaking

not as constables, but as their assistants – leading to the

first WPC section at Scotland Yard in 1922, though the

WPC was only paid 9/10ths of her male colleague’s wage.

After the First World War, the entry requirements were

relaxed a little – minimum height for men was now 5′ 9”

rather than 5′ 11” – and service conditions again improved,

as the pension was now granted after 30 years service.

In 1937 the first two police dogs were taken on strength,

‘Policewomen are regarded as specialists in all matters

but only lasted 18 months. However, the experiment was relating to the Children and Young Persons Act’

adjudged a success, and in 1947 the first Dog School was from the Evening News London Year Book 1953

opened at Kenton.

Although berated as ‘working class traitors’, the Metropolitan Police provided substantial assistance to the government

during the 1926 General Strike. For the Second World War, the police were equipped with steel helmets, and

acquitted themselves well during the chaos of the Blitz of 1940-1941. WPCs were prominent in the evacuation of

children from the capital in 1939. Postwar, WPCs proved themselves in other ways, as when WPC Margaret

Cleland was decorated with the George Medal for talking calmly to a deranged father clutching his baby and

threatening to jump off a precarious roof, until she managed to grab the baby to safety and ‘fortunately chummy

did not fall off’.

Scotland Yard’s famous Crime (‘Black’) Museum is alas not open to the public, though Maggie Bird recommends

a very good one in Manchester. However, the River Police Museum in Wapping is open to the public, being

maintained by the Metropolitan Police Association, not the Police Authority. And the National Archives at Kew

hold about nine miles (!) of London police files in class MEPO.

David Haunton

[See Coal and Calico p.158 for a good example of Bow Street detective work. The ‘Mounted Horse Patrole’

[sic] was operated from Bow Street.]

WHO REMEMBERS THE ASTON BANJO CLUB?

A recent enquiry from Debbie Foster, an ex-Merton Park resident who now lives in Devon, related to an

organisation called the Aston Banjo Club. There were blank faces all round until I consulted Sarah Gould,

Merton Heritage Officer. The name struck a chord (sorry) with her, and in no time she located a little booklet

from 1981 called The Aston Banjo Club: A Short History.

The Club was not named (as I first wondered) after Aston Road, Raynes Park, but Aston Street, Stepney,

which was where Harry Marsh, who founded the Club in 1896, had his home. Later he married, and in 1909

moved to Boscombe Road, Merton Park, and the Club’s headquarters became the parish room of Holy Trinity,

Wimbledon. Their instruments were quite varied, including banjeaurines, banjolos and piccolo banjos, mandolins,

and of course a piano. Over time they moved towards a greater number of plectra-rather than finger-played

instruments. There were dinner dances and outings, as well as competitions with other clubs and orchestras. A

highlight was their big annual concert, held mostly at various halls in Wimbledon and Merton Park, though

Kensington town hall was the venue for a few years. By the date of the booklet they had filled Wimbledon’s

Civic Hall several years running. The Club achieved its centenary in 1996, but sadly disbanded shortly afterwards.

Debbie Foster writes that she would love to find out more, particularly in connection with her grandfather

William Thomas Long and his father William James Long, who both had a long association with the club.

William Thomas apparently met his future wife, Elsie Foxcroft, at the Club, where she was the pianist. This was

during the 1920s. Debbie would appreciate hearing from any readers with memories of the Aston Banjo Club.

If you have any information please also share it with Bulletin readers.

JG

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 5

‘KINGSTON UPON THAMES – 800 YEARS AS A ROYAL BOROUGH’

The Snuff Mill Centre was full to overflowing for this talk on 31 January, given by Jill Lamb, Kingston’s

Archivist and Local Studies Manager. Last year was the 800th anniversary of the granting of a charter by King

John in 1208 that gave Kingston the right to raise its own taxes, and saw the birth of an independent community.

The charter document survives as the oldest of 32 in the archives.

Jill Lamb explained that by the year 1200 Kingston

was one of the richest places in Surrey. The church of

All Saints had been built about 1130, and the original

wooden Kingston bridge (just north of the present one)

some 50 years later. A market existed on the present

site; there were taverns and wine shops, and a Guild

merchant to regulate trade, which included whiteware

pottery manufacture. By 1300 Kingston held its own

courts and had an annual eight-day fair, but the town

was still very small and the main part round the Market

Place was effectively an island surrounded by marshes.

The Lovekyn chapel was built in 1309; it can still be

seen today in the grounds of Kingston Grammar School,

and is used for civil weddings and other events. In the The Lovekyn Chapel in 1886, after restoration.

14th century the town experienced high taxes, political Photo courtesy of Kingston Grammar School.

unrest, and the plague. The building of Hampton Court in the 1520s was of great importance to Kingston. Many

local craftsmen were employed, and material and supplies came through the town. The number of court visitors

encouraged the growth of inns and taverns. Kingston Bridge was still the first bridge upstream from London

Bridge and therefore a vital strategic link.

A charter of 1628 gave Kingston the right to be the only market within a radius of seven miles, a right tested in

court as late as the 1970s, when Brentford tried to establish a market. Brewing had become an important

industry and the name of the wealthy Tiffin brewing family survives in schools that they helped to found. During

the turbulent period surrounding the Civil War, Kingston suffered from the quartering of troops in the town and

political interference, and did not regain all its ancient rights until a Charter of 1688. In the more settled 18th

century the population continued to grow steadily (1200 in the year 1600, 2700 in 1700 and 4500 in 1800), and

Kingston had several coaching inns, as it was the hub of four turnpike roads. However, it was still a small town

surrounded by agricultural land. The medieval bridge was replaced by a stone bridge in 1828. In the early 19th

century Kingston Corporation was under-resourced and unable to deal with the new demands of a growing

population following the coming of the railways. The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 swept the old order

away and replaced it with a new administration. In despair at Kingston’s efforts to provide facilities Surbiton

and New Malden took over their own governance. They were generally regarded as more upmarket than

Kingston, which was very much a working class town.

Many new facilities and public buildings were established around the end of the 19th century, when the population

had reached 34,500. The economy was becoming more varied as the importance of the market declined. Some

1000 Kingston men lost their lives in the first World War, when the East Surrey Regiment was based in the town

and the Sopwith aircraft factory was established, later to become Hawkers. Light industry increased in the 20s

and 30s and Kingston grew in importance as a shopping centre. Bentalls, who started in 1867, rebuilt the store

in 1935 to a magnificent design by Aston Webb inspired by Hampton Court Palace.

After the second World War, for the first time Kingston seriously addressed the need for more council housing,

and there were several large housing developments. Kingston’s population had remained static since the 1920s,

but Surbiton, Tolworth and New Malden had grown enormously since the building of the by-pass in 1927. Local

government reorganization brought about the amalgamation of the boroughs into the new London (and Royal)

Borough of Kingston upon Thames in 1965. In the last 40 years many industries have gone, but Kingston

remains a major shopping centre and a significant number of people are employed by Kingston Council, Surrey

County Council and Kingston University – all situated in the town. Jill Lamb ended on an optimistic note : it is

hoped to develop Kingston as a cultural centre with the Market Place at the heart of the Cultural Quarter – a

far cry from the market trading of the 13th century.

This was a well-illustrated talk packed full with facts, in whch Jill Lamb displayed a comprehensive knowledge

of the subject : it was a commendable attempt to pack 800 years of Kingston history into a talk of just an hour.

David Roe

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 6

A CRICKET SOUVENIR

The Mitcham Cricket Club Year Book for 1946 includes the names of Colonel Bidder, ‘Burn’ Bullock, Andy

Sandham, Hubert Strudwick and Tom Francis as Vice Presidents.

On 22 May that year a benefit match was arranged versus the Surrey 1st Eleven for Alf Gover and Tom

Barling, and there were also special activities to support the Surrey County Cricket Club Centenary (18451945)

Appeal, to make the Kennington Oval one of the finest grounds in England. Proceeds from a match on

the Green against a Surrey 2nd Eleven on 19 June would go to the appeal. However, there is no mention,

probably because details were not available in time, of an even greater fund-raising match. On Thursday 23

May Surrey v ‘Old England’ was to be played at the Oval. This turned out to be a truly remarkable event,

attended by 15,000 spectators, including King George VI.

Surrey faced a side comprising ten Old England players and Brooks, former Surrey wicket-keeper, the one

member of the eleven without the honour of Test Match experience. Altogether the caps gained by the ten

players and the umpires Hobbs and Strudwick numbered 370. On one of the finest days of the season the

cricket proved full of interest. Runs always came fast, and there were three stands of over 100. Gregory and

Squires put up 111 for Surrey; Woolley and Hendren hit up 102, and Hendren and Jardine 108 for Old England

in a splendid effort to hit off the runs after Bennett, the new Surrey captain, declared. Fender was prominent in

the field, making a neat catch and taking two wickets with successive balls. The most exhilarating cricket came

after the fall of Sandham and Sutcliffe for two runs. Woolley, at the age of 59, drove with the same ease that

delighted the crowds before and after the 1914-18 war. Hendren showed all his cheery forcing play until, just

before time, he lifted a catch off Surrey’s most famous recruit, A V Bedser, already marked for England

honours. To stay two and three-quarter hours and hit eight fours at the age of 57 was a great feat by Hendren.

D R Jardine, wearing his Oxford Harlequin cap, was as polished as ever in academic skill. The match was

drawn. Surrey declared at 248 for 6. Old England reached 232 for 5 before time ran out.

After the match my uncle succeeded in buying an auctioned copy of the Mitcham Cricket Club Year Book

autographed by all those great players. And he gave it to me.

Cyril Maidment

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 7

LOCAL HISTORY WORKSHOPS

Friday 21 November 2008 at Wandle Industrial Museum. Evening meeting. Five present.

Cyril Maidment in the chair.

©

¨¨¨¨¨ David Haunton, who subscribes to Current Archaeology, had brought along the December issue, which

had a ten-page article on Merton priory by David Saxby and two colleagues. Excavations on the site of this

medieval powerhouse, as they called it, had yielded painted plaster, stained glass and a (rather unmonastic)

gold ring.

A gold finger-ring

recovered from a

demolition deposit in the

former infirmary hall,

inscribed [Je] ne weil

aymer autre que vous

(‘I am not seeking to

love anyone but you’).

Presumably it belonged

to a high-ranking lay

visitor.

David had been learning more about Eric Jean Reville, who, with a confectioner called Palmer, created at

Merton Rush the Palmer-Reville miniature racing car. Reville had a fascinating, if irregular, private life,

which David was untangling, and the little racing cars had quite a celebrated, if brief, career. See pages 1014.

¨ We were then treated to a selection of Bill Rudd’s fine black-and-white photographs of Morden street

scenes and buildings. These had been taken mainly in the 1960s and included long-gone Cinema Parade in

Aberconway Road, and Morden Park Cottages in London Road, and also Morden Park baths when brand

new, and the site of Merton College.

¨ Judith Goodman had been in electronic correspondence with someone in Carshalton who is interested in

the Wandle, and in fly-fishing. Like her, he has been unable to find the often-cited ‘Wandle trout spotted like

tortoises’ in Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler. Indeed the Wandle is not mentioned at all in that book, and

there is no reason to think Walton even knew of the river. His London river was the Lea.

¨ Cyril Maidment is interested in the garden gate at Abbey Gate House, a drawing of which appears in W

H Chamberlain’s Reminiscences of Old Merton (1925). His thoughts about its significance appear on page

14.

He had also brought along copies of some

Vincent Lines drawings of Morden, which

were admired.

Judith Goodman

B615 Wimbledon – West Croydon March 1929

photo: H G Casserley (see report on facing page)

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 8

Friday 9 January, afternoon meeting. Six present. Judy Goodman in the chair.

©

Cyril Maidment referred back to the Vincent H Lines drawings of Morden from the Wimbledon Society

Museum. Now 80 years old, they gave some details of local history not found anywhere else. Charles Toase

had now kindly provided the important accompanying text, but this does not reproduce well, nor can the poor

1920s/1930s newsprint be digitised by the OCR process. Sixty half-page articles need to be put on disk by a

copy typist in preparation for the Lines centenary. Could any Society member volunteer?

In the Bulletin for September 2005 there were three items relating to cricket in Mitcham. One was about a

copy of Mitcham Cricket Club’s 1946 Year Book, the cover of which had been autographed by some very

famous players on the occasion of Old England playing Surrey at the Oval on 23 May 1946. Cyril had

unearthed some more facts about this event and about the Year Book. See page 7 of this Bulletin.

©

Peter Hopkins had been even more industrious than usual. With the medieval court rolls of Morden he had

prepared a spreadsheet with 10600 entries, enabling all manner of studies to be undertaken. Copies of

documents had been received from the National Archives, including a grant of 1362 by William de Mareys

to the perpetual vicars of Mitcham, and Westmorden. Also he had received a 16th-century document relating

to Sparrowfield Common. After much seeking he had found a good researcher to deal with certain documents

of Morden church and vicarage. He had also obtained a quotation for translating the 14th-century copy of

the Merton priory foundation narrative in the College of Arms. This would probably cost about £1000.

Workshop considered this would be an excellent use for part of the Maud Gummow bequest.

Surrey History Centre has recently purchased an album of photographs of the plant and operations at

Renshaw’s marzipan factory in Mitcham.

Sarah Gould had passed to Peter a typescript Memoirs of a Morden Lad, who had lived in Central Road

from 1932 to 1957. It would be considered for publication, as would the 19th-century poem Ravensbury,

copies of which had been given to members at the previous workshop.

©

Lionel Greenhad obtained copies of seven interesting railway photos relating to Mitcham (see the example

at the foot of facing page).

He had also brought with him a little book by Rose E Selfe called

The Work of the Prophets (1906), which has local interest as four

of the eight illustrations are photographs of paintings by Frederic

Shields, who lived at Long Lodge, Merton Park. He painted them

for the Ascension Chapel in Bayswater, which was unfortunately

destroyed in the last war, and all its decoration lost.

Lionel reported that the latest newsletter of Leatherhead and District

Local History Society had a note about Coal and Calico. Calico

printer John Leach had retired to Bookham.

¨ David Hauntonbelieved he had deciphered the ‘illegible’ word

reproduced on page 158 of Coal and Calico. He suggested that it

was the Scottish word ‘throch’, and that the housemaid was in fact

armed with a chamber pot! See page 15.

¨ Judy Goodman mentioned the 19th-century boys’ school in old

Church House, Merton Park. Charles Toase had sent her a copy of

an 1893 advertisement from The Times placed by the school’s

proprietor. The school will be the subject of a future Bulletin article.

She had also, thanks to Sarah Gould, been able to answer an enquiry

Zechariah about the Aston Banjo Band. See page 5. Isaiah

She had had an enquiry from a regular correspondent who had sent a photo (undated) of part of Young’s

Accumulator establishment on the Kingston Bypass, asking her to identify a cupola at one side of the view.

The workshop felt it was most probably a feature of the ‘works’ building, which was alongside the ‘office’

building shown in the photo. It did not seem likely to have been on the Shannon Corner Odeon nearby, which

was apparently (we have no pictures of it locally) a white-tiled art deco building, unlikely to sport a cupola.

Can anyone remember?

Cyril Maidment

Dates of next Workshops: Fridays 13 March and 15 May at 2.30pm at Wandle Industrial Museum.

All are welcome. Note that workshops will be afternoon events from now on.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 9

DAVID HAUNTON is intrigued by

JEAN REVILLE: MERTON’S RACING MOTORIST – PART 1

This article is a tentative statement of work in progress. There are so many loose

ends that an alternative title might well be ‘Jean Reville: International Man of Mystery’.

Our hero was a racing driver and racing car maker, based in Merton Park. He was

briefly famous during 1934 and 1935 in the brand new sport of midget car racing. This

enjoyed a short-lived vogue in Britain before the War, employing tiny purpose-built

cars which hurtled round three or four laps of a small oval dirt-track course.

Early Days

‘Jean’ Reville was his preferred publicity name. His given names, as reported in

Merton and Morden Voters Lists, were Eric Jene (consistently so spelt). Here I shall

refer to him as Jean. We do not know where he was born, but from his 1928 marriage

certificate we learn that his father, James Jocelyn Reville, was a flour miller and Jean Reville (Wimbledon

manager, and that Jean was then 28 years old, so born c.1900. However, the family Boro’ News 4 May 1934)

do not appear to be in the 1901 census or those parts of the 1911 census available at

present. (Is immigration more probable than name change?)

Jean married Daisy Florence Epsom ‘otherwise Palmer’ of Croydon, at Hammersmith Register Office in

1928, describing himself as a confectionery salesman. By May 1929, the couple had moved into 3 Merton Park

Parade, a confectionery shop. There they joined Arthur Thomas Palmer and his wife Elizabeth Jane, who had

been in residence and keeping the shop since 1914. (I believe that, to hold a lease or own a freehold, Arthur

must have been over 20 years old in 1914, so he would be at least 35 in 1929.) Intriguingly, in 1929 Jean and

Daisy married again, this time in St Mary’s Church in Merton Park, with Jean now a ‘motor engineer’. (What

was the impediment to the first wedding?) I presume that Daisy was a relation of the Palmers. It is curious that

she is entered in the Voters List for October 1929 under her maiden name of Epsom, with her qualification

being that of the wife of a resident. In the 1930 Voters List, Daisy is safely ‘Reville’ and remains so while in

Merton.

At this point we should note that the Merton Park Parade of shops, with flats above, curves round from

Kingston Road into Watery Lane. Nos.1–12 form a continuous terrace and were built in 1907. Then there is an

open plot (thus avoiding any need for a no.13), and then a detached showroom, no.14, which was added in 1930

with an unusual triangular groundplan. The open plot and no.14 have always been occupied together, by motor

engineers and/or traders.

In 1930, Arthur and Jean started a new venture called Palmer Reville & Co. This offered ‘motor hire services’

based on 3 Merton Park Parade. The following year they raised sufficient capital (from whom?) to move this

business to no.14, while Arthur retained and continued the confectionery shop at no.3. In 1931 they were

joined by Dennis James Reville and his wife Grace Gladys, who occupied 14A Merton Park Parade, the flat

above the showroom. I believe that Dennis was a younger (?) brother of Jean, who assisted at Palmer Reville

& Co. I presume they erected some sort of temporary workshop and garage on the open plot, where they

began to modify BSA front wheel drive sports cars, which they offered for sale under the tag of ‘Palmer

Specials’. They were sufficiently successful in this that by the end of 1933 they could offer three different

versions – the ‘Ulster’ 2seater

and ‘Le Mans’ 4seater

for touring, and the

‘Brooklands’ 2-seater for

more dedicated sportsmen.

Recent photo of a 1933 Palmer

Reville Ulster model

(website bsafwdc.co.uk,

courtesy Merton Library and

Heritage Service)

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 10

Advertisement showing Brooklands model

(The Autocar 13 October 1933)

The Sport

There were many car-based competitions in the 1920s

and 1930s – time trials, rallies, hill climbs, economy runs,

even a few road races on private land. All over the

country young men with spanners modified and tuned

some of the immense variety of small cars available.

Motorcycle racing on dirt-tracks began in the mid-1920s;

car races with standard roadsters on the same tracks

were occasional events that became more frequent

during the early 1930s.

The first dirt-track meeting for midget cars featuring

specially-designed vehicles was held in June 1933 in

Sacramento, California. This exciting new sport rapidly

became widely popular across the USA and then crossed

to Britain in 1934. Chiefly performed at greyhound racing

and motorcycle speedway stadiums, the sport was

calculated to attract a more numerous, working-class,

paying audience than traditional motor racing, where fans

tended to be more upper-class. Normally a programme

contained a dozen or more races.

First Racing Car

I suspect that Jean acquired his racing experience in amateur sports over the period 1929-1933. He certainly

drove in dirt-track races during 1933 (eg. at Wembley Stadium in early August), using a BSA sports car ‘of

somewhat special attributes’. Since the firm’s later cars were known as Palmer Specials rather than Palmer

Revilles, I speculate that at the same time Arthur was developing expertise in car modification.

Arthur Palmer and Jean Reville decided that they could exploit the new midget racer arena, and so created a

single-seat midget Palmer Special towards the end of 1933. This was a variant of their existing designs, with

small wheels and a low, narrow and rather crude body, in which the cylinder heads of the ‘Vee’ engine protruded

through the bonnet. The driver’s seat was moved to the centre-line, but the steering wheel remained in its

original position, so that the steering column pointed at the driver’s right shoulder. Versions were offered for

sale for £180 ‘including engine mods’. This was raced during the 1934 season, and was evidently improved and

‘cleaned up’ as time went on. A few (two or three?) further examples were produced.

left: Early Palmer Special, Reville in car, Palmer (?) standing.

above: Early Palmer Special. Boy is holding a normal size BSA wheel.

(both from Bridgett, Midget Car Speedway p.20)

Jean Reville threw his energies into promotion and publicity. He set up a Speedway Racing Drivers Club, based at

14 Merton Park Parade, which organised the first British race meetings for midget cars, at Crystal Palace, and

drew up rules for size and engine capacity of the cars. The first meeting was on 31 March 1934 (Easter weekend),

and Reville interested Paramount Films sufficiently for them to send a film crew. Both the first and the second (14

April) meetings were advertised in the Times, as was another on 26 May. All these were on Saturdays. Also in

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 11

May, he posed for a publicity

picture with the Hon. Victoria

Worsley, a socialite and racing

driver, before her attempt at a

lap record at Crystal Palace on

Whit Monday (the Wimbledon

Boro’ News calling him ‘the

well-known local racing

motorist’). As well as this

activity, Jean was racing at

least once a week throughout

a season lasting until

September; at Crystal Palace

this was often as the captain

of the local team of three

drivers. By 23 November 1934

The Autocar could describe

him as ‘the originator of

miniature-car dirt-track racing

Late-model Palmer Special (The Light Car 30 November 1934)

in this country’.

The Gnat

In November 1934, Reville’s publicity machine announced a new car in the motoring press, while the Wimbledon

Boro’ News had an early picture of Reville himself in ‘his latest baby car’ on 7 December. This was the Gnat,

a specially designed midget racer with a 992cc JAP motorcycle engine, one gear and one small brake. Initially

the exhaust pipe ran between the driver’s knees, which ‘must have added to the excitement’. Only six feet long,

the Gnat was billed as the ‘World’s Smallest Racing Car’, with ‘Jean Reville’ prominent in its paintwork, and

‘Palmer Special’ rather more quietly across the radiator. In January, The Light Car had portrait photos of the

machine itself, and commented approvingly that the ‘Palmer-Reville duo had done a great deal of serious

thinking on the subject of the right kind of dirt-track car’. This was followed on 1 February by news of design

changes as a result of testing. (But where were the test runs held?) Later opinion was not so flattering;

‘unbelievably crude’ was one Australian comment delivered decades later with 100% hindsight – but what else

could be expected of two pioneering young men with spanners?

Side view of the Gnat

(The Light Car 11 January 1935)

During February 1935 a certain

unreality creeps into the publicity

– there are reports that Jean

Reville has plans to produce 50

machines ‘by Easter’, backed by

a company with ‘unlimited

capital’, and that he intends to

take a team of six English drivers

to California to compete against

‘the Americans’. Such euphoric talk may have been stimulated by meeting Joel ‘Joe’ W Thorne, the playboy

American heir to two millionaires, pilot, and driver of fast cars, boats and motorcycles. The two men were

pictured in the local press in February, Thorne having just competed in the Monte Carlo Rally, and genially

agreeing he would raise a team of midget racers (in the USA) and return in the summer. (On 21 February he

sailed for New York from Southampton aboard the luxurious Ile de France, and apparently did not return to

Britain before the Second World War: at least, he did not again leave Britain by ship in that period.) Of course,

all Jean Reville’s talk may have been ‘shooting a line’ with his tongue firmly in his cheek. He must have known

that producing 50 Gnats in eight or nine weeks was quite impossible on the Merton Park premises – in the event

it seems only five or six machines were made over the next few months.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 12

Jean had a very busy and successful 1935 racing season,

with much publicity. For example, he won three races at

Crystal Palace on Easter Monday, raced at the Silver

Jubilee meeting at White City in May, and the second

Lea Bridge meeting on the Saturday before Whitsun, and

competed in three meetings over Whitsun – on the

Saturday at the opening meeting of the Perry Hill Stadium

in Catford, on Whit Monday at Crystal Palace in the

afternoon, and at Lea Bridge Stadium in the evening.

Probably his last appearance on a British track was at

the recently opened Wimbledon Stadium on 1 September.

below: Joe Thorne standing by his Monte Carlo car, Jean Reville

in Gnat (Wimbledon Boro’ News 15 February 1935)

above: Driver’s view of the Gnat

(The Light Car 11 January 1935)

This was a two-car match arranged by the

stadium management to test the interest of the

local greyhound racing (known locally as

‘gracing’) and motorcycle speedway fans. In the

event, his opponent’s car ‘refused to function’

and Jean was reduced to driving a solo

demonstration run, which was adjudged

‘insufficiently interesting’. This seems to have

been the only occasion on which midget racing

cars were shown at Wimbledon.

And Away …

At some point in 1935, Arthur Palmer

Gnat after modifications

had relinquished the sweetshop at 3

(South London Press 24

April 1935) Merton Park Parade and taken a

newly-built double-fronted shop at

215/217 Kingston Road, Ewell,

where he sold toys and prams as well

as confectionery. All six Palmers and

Revilles moved into the new

accommodation. Dennis continued

the motor hire service until 1937,

when 14 Merton Park Parade passed

to Mr A G Spencer, motor engineer.

With the end of the 1935 British

season, Jean Reville accepted a

contract to race for a season in

Australia, along with two other

drivers. They were to tour as an

‘England’ team using three Gnats and competing against local drivers and machines. Reville was billed as the

‘British Champion’; the other two were ‘Bud’ Stanley (allegedly of Wimbledon, but whose given name no-one

seems to know) and Ralph E P Secretan. On 13 September 1935, Jean Reville ‘racing motorist’ sailed from

London for Sydney aboard the SSOrsova, together with Ralph Secretan and his wife, but without his own wife

Daisy. And he never came back.

The team had a good Australian season, starting at the newly-opened Sydney Showground on 2 November, and

later going on to race at Melbourne and Brisbane. Stanley and Secretan returned to England in early 1936, but

Reville stayed on in Brisbane. (Why?)

According to my Brisbane correspondent John Williams, Reville subsequently had a successful racing career in

Australia, supplemented by a motor-import business and various half-hearted engineering enterprises. In 1945

he married the daughter of William Jolley, the mayor of Brisbane, and they later had a son. (What had happened

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 13

to Daisy? She had not sailed for Australia by 1948.) Jean Reville remained in Brisbane until he died in the early

1980s. Sadly, in later life he made many claims about his involvement with English midget car racing, but most

if not all are exaggerated or false. (See Part 2.)

Arthur Palmer occupied his new shop with its prams and toys until at least 1960, when he presumably retired.

The shop, with its window display of a working electric train set, is still fondly remembered in Ewell. I must also

admit to a soft spot for Arthur Thomas Palmer, confectioner and racing car designer (part-time).

Acknowledgements

Derek Bridgett, author of Midget Car Speedway (2006), Tempus Publishing Ltd, for much help, for copies of

many cuttings he culled from The Light Car and Cyclecar magazine (usually referred to as The Light Car),

The Autocar magazine, and other press notices, and for starting this whole enquiry by his letter to the Wimbledon

Guardian.

John Williams of Brisbane for encouragement, information and long phone calls from Australia. (John is a

Welshman whose parents met in Wimbledon, so he is one of us, and therefore a Good Chap.)

Merton Local Studies Centre for local newspapers, directories, Voters Lists, and finding our first illustration.

Volunteers at Epsom and Ewell Local Heritage Centre for memories.

THE ‘HIGHGATE’ OF MERTON PRIORY

Some years ago I studied the matter of access to Merton priory, and in particular the functions of two gates in

Station Road, opposite each other, and separated by the width of the road, say 20 metres. Was there a reason for

them to be exactly facing each other? The much-loved southern gate, with a round arch, survived until the 1980s,

but the northern gate, with a pointed arch, must have disappeared soon after our drawing was made in 1925. The

elaborate small towers on either side of the gate suggested that this was no more than a ‘folly’ built to please an

owner of Merton Abbey Gatehouse. In the photograph, taken from inside the wall, one can see the railings at one

end of the long thin ornamental lake, most of which was exactly replaced by the line of Mill Road. Imagine my

delight to find on page 122 of the MoLAS book on Merton priory that the gate was ancient and was known as the

‘Highgate’. The photograph shows clearly much flint still apparent in the wall, indicating that it was part of the

priory. Indeed the wall surrounded the grounds of the gatehouse and also covered the length of Abbey Road. In the

late 17th century John Aubrey noted the existence of the Highgate in his Natural History and Antiquities of

Surrey (pub. 1718-1719).

One wonders why walls existed on both sides of this lane (Station Road). Two possibilities exist. The lane was

open to public access, with a further gate at the present river crossing, or thereabouts – the main course of the

river Wandle being east of the priory during the life of the

priory. The other possibility is a grand entrance gate at the

junction of Station Road, High Path and Abbey Road. Dave

Saxby, who has spent many years excavating the priory

and its surroundings, considers that this is not unlikely.

Cyril Maidment

Right: The ‘Highgate’ from Station Road, signed ‘L.B.T. 1925’

Above: The ‘Highgate’ from the garden side, photographed before

1915 (Wimbledon Society Museum)

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 14

DAVID HAUNTON does not wish to be taken too seriously as he discusses

IDEAS ON [illegible]

On p.158 of Coal and Calico (transcribed from the notes hand-written by the aged Canon Frederick Bennett

in 1896) the account of the 1826 burglary contains the following:

‘… he heard some one behind him. It was my Mother with the Poker & the Housemaid with the[illegible] of the Bedroom, prepared to assist in the defence’.

What, wonders Judith Goodman in a picture caption, is [illegible]? Keen to assist, I recruited my daughter, who

is currently attending a paleography course, and after some time and argument we agreed that [illegible] reads

something like Throch, with plausible alternatives Throck, Thooch or Throoh.

And so off to Wimbledon Library, there to consult the full Oxford English Dictionary. It contained not a single

entry for any of our three plausibilities.

Happily, however, Throch ( or Throckt) though obsolete, Scottish and undefined, did give us cross-references

to Throuch, Through and Trough.

Throuch (or Through) is a sheet of paper. An unlikely weapon.

Through (or Thorough) yields several possibilities:

(1)

a trough, pipe or channel for water. But only in Old English (ie. Anglo-Saxon).

(2)

a hollow receptacle for a dead body

(3) a large slab of stone laid upon a tomb.

Neither of these is likely to appear in a bedroom, and either of them is a bit heavy for a housemaid.

(4) various ladder-rungs and express messengers, which eliminate themselves from further consideration.

Trough offers an encouraging range of possibilities (nearly two columns of the OED):

(1)

a narrow open box-like vessel … to contain liquid; also a tank or vat for washing, brewing, tanning, fulling,

and ‘various other purposes’.

Variants on this are a small vessel used in chemistry or photography; a toper (a mere container for liquids);

or a dining table or a meal. These we can dismiss.

(2)

other boxes with special uses involving grindstones, voltaic batteries, or washing ore in a mine (though you

may call that one a buddle, of course)

(3)

a small primitive boat, a dug-out or Trow (though there is no unanimity on this: in different parts of Britain

it is a large flat-bottomed sailing barge, a double canoe for spearing salmon by torchlight or a small flat-

bottomed herring-fishing boat)

(4)

a stone tomb or coffin (see above)

(5)

a conduit or gutter for conveying water

(6) a hollow or valley in sea or land.

Coming up for air, and after mature consideration, we are left with some sort of container for liquids, to be

found in an early 19th-century bedroom. It must be portable, but reasonably hefty, to be thought of as a weapon.

One obvious possibility is the jug or ewer from a jug-and-basin washing set, but in that case why would the

good Canon not just call it a jug? To employ an unusual word seems to imply some delicacy on his part; which

leads me to suggest he intended either the slop-pail from a putative jug-and-basin set, or the conversationally-

dreaded chamber pot. Given the choice of wielding the former, with its uncertainly swinging handle, or the

latter, with its reassuringly firmly fixed handle, I would opt for the chamber pot.

I rest my case.

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 15

THE WANDLE IN LITERATURE – an occasional series

6. John Ruskin

John Ruskin (1819-1900), artist, critic, polymath and social reformer, published

his autobiography in parts between 1885 and 1889. He called it Praeterita –

‘Things Gone By’. By this period of his life he was suffering severe bouts of

insanity, and the book was never completed. But the first few chapters had

been written much earlier; they were based on some of his writings in Fors

Clavigera (Ruskin never went in for straightforward titles. This one, he

said, meant Chance, or Fortune, with the nail). Fors was his series of letters

‘to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain’, which he began in 1871.

His description of his life as a small boy is fresh, vivid and touching. He was

the only child of parents who combined strictness with indulgence in his

upbringing. His Calvinist mother made him read the Bible aloud every morning;

he was whipped frequently; he was allowed no toys except a box of bricks;

he was never permitted a dessert. But his time was his own from noon each

day till supper and he early began his meticulous observation and depiction of

every detail of his surroundings. Moreover, every year there was a long tour

with his parents, in this country or on the Continent, for his father was a

prosperous wine merchant. These early experiences sowed the seeds of the

intense appreciation of nature, architecture and art that so influenced his future career.

An attractive aspect of Ruskin’s character is that he was no snob. He dearly loved, and loved to be with, the

humble maternal relatives who lived over their baker’s shop in Croydon’s medieval Market Street. And when he

stayed with them he had the chance, he wrote, to ‘walk on Duppas Hill and on the heather of Addington’. Was it

on these visits that he got to know the Wandle? Perhaps. At the end of Praeterita’s first chapter is this passage:

‘… [W]hile I never to this day pass a lattice-windowed cottage without wishing to be its cottager, I never yet saw

the castle which I envied to its lord; and although in the course of … many worshipful pilgrimages I gathered

curiously extensive knowledge, both of art and natural scenery, … it is evident to me in retrospect that … the

personal feeling and native instinct of me had been fastened, irrevocably, long before, to things modest, humble,

and pure in peace, under the low red roofs of Croydon, and by the cress-set rivulets in which the sand danced and

minnows darted above the Springs of Wandel.’ (Ruskin chose to use this spelling.) The chapter is called ‘The

Springs of Wandel’.

In 1866 Ruskin published three polemical lectures, ‘Work’, Traffic’ and ‘War’, in a volume which he called The

Crown of Wild Olive. His introduction begins with another famous reference to the Wandle:

‘Twenty years ago there was no lovelier piece of lowland scenery in southern England … than that immediately

bordering on the sources of the Wandel … with all their pools and streams. … The place remains … nearly

unchanged in its larger features; but … I have never seen anything so ghastly … as the slow stealing of aspects of

reckless, indolent, animal neglect, over the delicate sweetness of that English scene … Just where the welling of

stainless water … enters the pool of Carshalton … the human wretches of the place cast their street and house

foulness. … Half-a dozen men, with one day’s work, could cleanse those pools, and trim the flowers about their

banks. … But that day’s work is never given, nor, I suppose will be.’

Ruskin’s mother, Margaret, died in 1871, and in her memory he paid for one of the Carshalton pools to be tidied,

and its spring cleaned out. A plaque was installed, which read:

‘In obedience to the Giver of Life, of the brooks and fruits that feed it, of the peace that ends it, may this Well be

kept sacred for the services of men, flocks and flowers, and be by kindness called MARGARET’S WELL. This

pool was beautified and endowed by John Ruskin, Esq., M.A. LL.D.’

The pool, in the angle between West Street and Pound Street, still survives, and even has water in it sometimes –

after a wet winter. (A detailed account of the pool project is given by A E Jones in his From Medieval Manor to

London Suburb: An Obituary of Carshalton.)

Judith Goodman

Letters and contributions for the Bulletin should be sent to the Hon. Editor. The views expressed in this

Bulletin are those of the contributors concerned and not necessarily those of the Society or its Officers.

website: www.mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk email: mhs@mertonhistoricalsociety.org.uk

Printed by Peter Hopkins

John Ruskin aet 3½, 1822,

by James Northcote

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY – BULLETIN 169 – MARCH 2009 – PAGE 16

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

MERTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY